In ordinary life we shift frequently between observing the world before us and summoning impressions from memory. Reproducing this experience in fiction can require an immense sophistication of the reader. In Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method (1983), Gérard Genette examines a passage from Proust’s Jean Santeuil in which Jean finds the hotel in which lives Marie Kossichef, whom he once loved, and compares his impressions with those that he once thought he would experience today:

“Sometimes passing in front of the hotel he remembered the rainy days when he used to bring his nursemaid that far, on a pilgrimage. But he remembered them without the melancholy that he then thought he would surely someday savor on feeling that he no longer loved her. For this melancholy, projected in anticipation prior to the indifference that lay ahead, came from his love. And this love existed no more.”

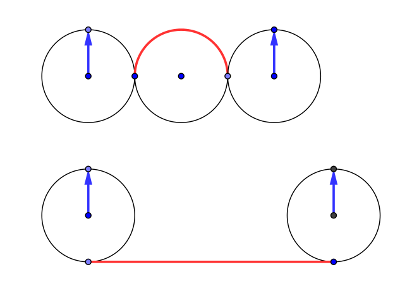

Understanding this one paragraph requires shifting our focus between the present and the past nine times. If we designate the sections by consecutive letters, and if 1 is “once” and 2 is “now,” then A goes in position 2 (“Sometimes passing in front of the hotel he remembered”), B goes in position 1 (“the rainy days when he used to bring his nursemaid that far, on a pilgrimage”), C in 2 (“But he remembered them without”), D in 1 (“the melancholy that he then thought”), E in 2 (“he would surely some day savor on feeling that he no longer loved her”), F in 1 (“For this melancholy, projected in anticipation”), G in 2 (“prior to the indifference that lay ahead”), H in 1 (“came from his love”), and I in 2 (“And his love existed no more”).

This produces a perfect zigzag: A2-B1-C2-D1-E2-F1-G2-H1-I2. And defining the relationships among the elements reveals even more complexity:

If we take section A as the narrative starting point, and therefore as being in an autonomous position, we can obviously define section B as retrospective, and this retrospection we may call subjective in the sense that it is adopted by the character himself, with the narrative doing no more than reporting his present thoughts (‘he remembered …’); B is thus temporally subordinate to A: it is defined as retrospective in relation to A. C continues with a simple return to the initial position without subordination. D is again retrospective, but this time the retrospection is adopted directly by the text: apparently it is the narrator who mentions the absence of melancholy, even if this absence is noticed by the hero. E brings us back to the present, but in a totally different way from C, for this time the present is envisaged as emerging from the past and ‘from the point of view’ of that past: it is not a simple return to the present but an anticipation (subjective, obviously) of the present from within the past; E is thus subordinated to D as D is to C, whereas C, like A, was autonomous. F brings us again to position 1 (the past), on a higher level than anticipation E: simple return again, but return to 1, that is, to a subordinate position. G is again an anticipation, but this time an objective one, for the Jean of the earlier time foresaw the end that was to come to his love precisely as, not indifference, but melancholy at loss of love. H, like F, is a simple return to 1. I, finally, is (like C), a simple return to 2, that is, to the starting point.

All in a passage of 71 words! And Genette points out in passing that a first reading is made even more difficult because of the apparently systematic way in which Proust eliminates simple temporal indicators such as once and now, “so that the reader must supply them himself in order to know here he is.”