G.H. Hardy had a famous distaste for applied mathematics, but he made an exception in 1945 with an observation about golf. Conventional wisdom holds that consistency produces better results in stroke play (where strokes are counted for a full round of 18 holes) than in match play (where each hole is a separate contest). So if two players complete a full round with the same total number of strokes, then the more erratic player should do better if they compete hole by hole.

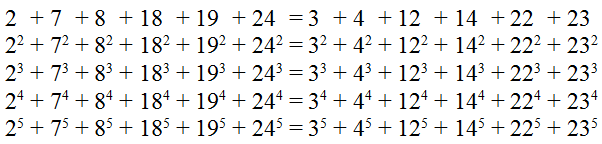

Hardy argues that the opposite is true. Imagine a course on which every hole is par 4. Player A is so deadly reliable that he shoots par on every hole. Player B has some chance x of hitting a “supershot,” which saves a stroke, and the same chance of hitting a “subshot,” losing a stroke. Otherwise he shoots par. Both players will average par and will be equal over a series of full rounds of golf, but the conventional wisdom says that B’s erratic play should give him an advantage if they play each hole as a separate contest.

Hardy’s insight is that the presence of the hole limits a run of good luck, while there’s no such limit on a run of bad luck. “To do a three, B must produce a supershot at one of his first three strokes, while he will take a five if he makes a subshot at one of his first four. He will thus have a net expectation 4x – 3x of loss on the hole, and should lose the match, contrary to common expectation.”

In general he finds that B’s chance of winning a hole is 3x – 9x2 + 10x3, and his chance of losing is 4x – 18x2 + 40x3 – 35x4, so that there’s a balance f(x) = x – 9x2 + 30x3 – 35x4 against him. If x < 0.37 -- that is, in all realistic cases -- the erratic player should lose.

"If experience points the other way -- and I cannot deny it, since I am no golfer -- what is the explanation? I asked Mr. Bernard Darwin, who should be as good a judge as one could find, and he put his finger at once on a likely flaw in the model. To play a 'subshot' is to give yourself an opportunity of a 'supershot' which a more mechanical player would miss: if you get into a bunker you have an opportunity of recovering without loss, and one which you are naturally keyed up to take. Thus the less mechanical player's chance of a supershot is to some extent automatically increased. How far this may resolve the paradox, if it is one, I cannot say, and changes in the model make it unpleasantly complex."

(G.H. Hardy, "A Mathematical Theorem About Golf," Mathematical Gazette, December 1945.)