Two things cannot occupy the same place at the same time. That seems reasonable. But:

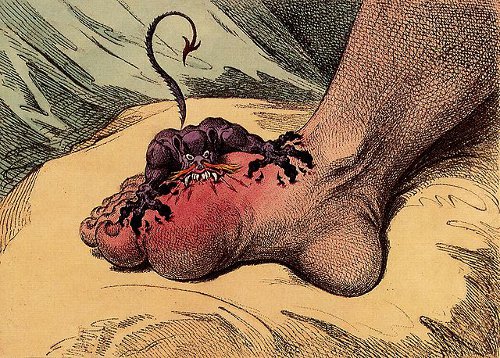

A cat called Tibbles loses his tail at time t2. But before t2 somebody had picked out, identified, and distinguished from Tibbles a different and rather peculiar animate entity — namely, Tibbles minus Tibbles’ tail. Let us suppose that he decided to call this entity ‘Tib.’ Suppose Tibbles was on the mat at time t1. Then both Tib and Tibbles were on the mat at t1. … But consider the position from t3 onward when, something the worse for wear, the cat is sitting on the mat without a tail. Is there one cat or are there two cats there? Tib is certainly sitting there. In a way nothing happened to him at all. But so is Tibbles. For Tibbles lost his tail, survived this experience, and then at t3 was sitting on the mat. And we agreed that Tib ≠ Tibbles. We can uphold the transitivity of identity, it seems, only if we stick by that decision at t3 and allow that at t3 there are two cats on the mat in exactly the same place at exactly the same time.

Tibbles and Tib were distinct material objects, but after the amputation they appear to occupy exactly the same space. Were we mistaken?

(From David Wiggins, “On Being in the Same Place at the Same Time,” The Philosophical Review, 77:1 [January 1968], 90-95.)

Further trouble:

No cat has two tails.

Every cat has one tail more than no cat.

Therefore every cat has three tails.