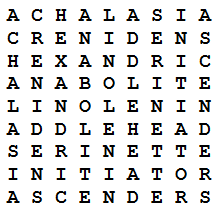

Large word squares are dramatically harder to make than small ones. To date the largest anyone has managed to find are composed of 9-letter words:

Finding a perfect 10×10 word square has been a central goal for wordplay fans for more than 100 years. The task was looking impossible when in 1972 Dmitri Borgmann found an unexpected resource in the African journal of David Livingstone, whose entry for Sept. 26, 1872, reads:

Through forest, along the side of a sedgy valley. Cross its head-water, which has rust of iron in it, then west and by south. The forest has very many tsetse. Zebras calling loudly, and Senegal long claw in our camp at dawn, with its cry, ‘O-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o.’

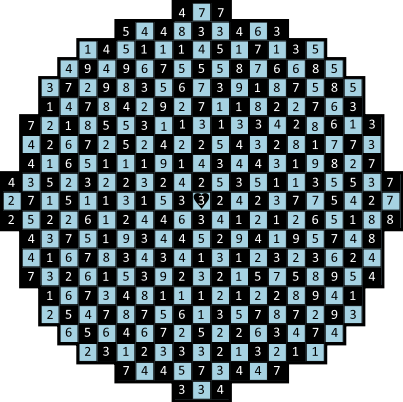

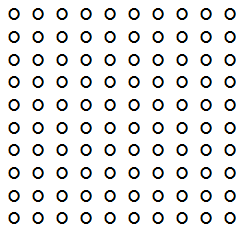

This is exactly what was needed. Given a pen, the yellow-bellied longclaw, Macronyx flavigaster, could have drawn for Livingstone a perfect 10×10 word square:

We ought to consult other species more often. Any longclaw could have given us this contribution — indeed, this is the only word square the bird is capable of making!