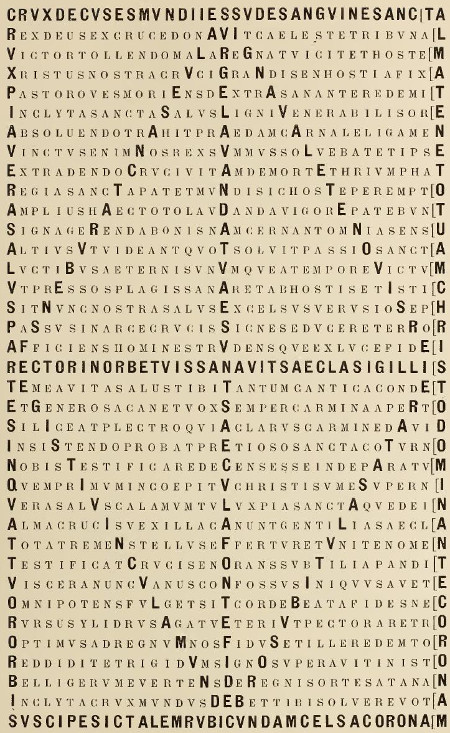

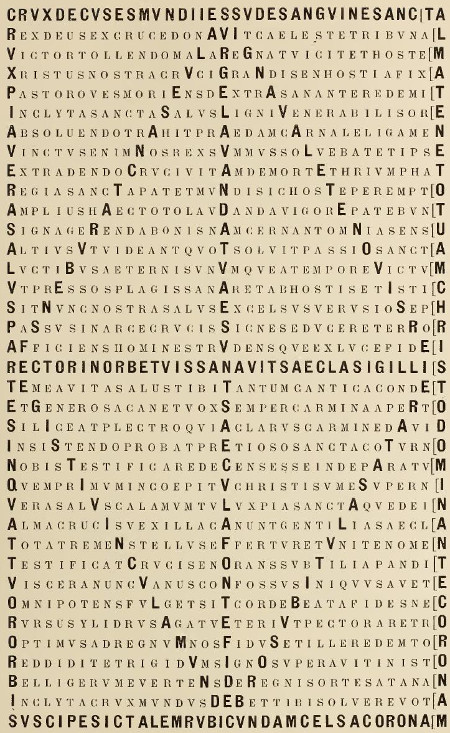

The English scholar Alcuin devised this remarkable acrostic poem in the ninth century. The text can be read in conventional lines of Latin, and additional phrases are embedded in a symmetrical arrangement of lines that represent the cross inscribed upon the world:

Horizontal, top and bottom:

Crux decus es mundi Iessu de sanguine sancta (“Cross, you are the glory of the world, in Jesus’ blood sanctified”)

Suscipe sic talem rubicumdam celsa coronam (“Accept, exalted cross, from me this scarlet crown”)

Vertical, left and right:

Crux pia vera salus partes in quatuor orbis (“Pious cross, true salvation in the four corners of the world”)

Alma teneto tuam Christo dominane coronam (“Beneficent, take your crown, Christ being the Lord”)

The cross:

Rector in orbe tuis sanavit saecla sigillis (“The ruler of the world saved generations by your sign”)

Surge lavanda tuae sunt saecula fonte fidei (“Rise, the world is cleansed in the font of faith”)

The diamond, representing the world (whose four corners are referenced in the vertical line on the left):

Salve sancta rubens, fregisti vincula mundi (“Hail holy scarlet, you have shattered the world’s shackles”)

Signa valete novis reserata salutibus orbi (“Wonders are manifest, revealed anew to the world in saving works”)

A translation of the full text:

Cross, you are the glory of the world, in Jesus’ blood sanctified.

God the king from the cross conveyed heaven’s judgment.

A victor he reigns, destroying evil and conquering the enemy,

Christ the great sacrifice nailed on the cross for us.

The shepherd by dying redeemed his sheep with his healing right hand.

Glorious, holy salvation from the venerable tree,

he seized the prize, shrugging off the ties of flesh.

Though in bonds the highest king freed us, and he himself

giving his life to the cross triumphed over death,

The kingdom of heaven gaped when the world’s enemy was destroyed.

The sign will be more manifest and all good people will wear it,

praising it with all strength; let all discern more profoundly

so that they may see how many his holy passion frees

from eternal sorrow, and see one thrown down by time

to heal those oppressed by the enemy’s torments; there

may the highest and true Joseph now be our salvation,

who suffered high upon the cross such that error can’t seduce

and poison men and drag them from the light of faith.

The ruler of the world saved generations by your sign.

You, my life, my salvation! For you alone my voice composes hymns,

and shall always sing the highest songs, clear and plain

with the plectrum; for David famous for his song

proves that it is proper for us to testify holiness continually

in elaborate style — accept that which I have just begun, O Christ supernal,

true salvation, great sufferer, you sacred and holy light. Now

the secular nations sing the beneficent sign of the cross,

all the earth trembles and in one accord proclaims

the fame of the cross. In prayer it reveals its inmost heart.

Now hear, vain men, confounded in evil:

The almighty shines forth. May blessed faith fill your hearts

and the serpent not drive them back to their old ways.

The highest and most faithful redeemer has restored us

to his kingdom, and has conquered by this sign the obdurate one,

toppling warlike Satan from the place he hazarded to rule.

Glorious cross, the world should loose its prayers to you.

Accept, exalted cross, from me this scarlet crown.

(From Monumenta Germaniae Historica, part one, 1880, and Jay Hopler and Kimberly Johnson, eds., Before the Door of God: An Anthology of Devotional Poetry, 2013. Thanks, Brandon.)