In 1921 someone began stealing money, jewelry, and clothing from a girls’ dormitory at the University of California. When the residents themselves were unable to identify the culprit, student Margaret Taylor made a formal complaint to the police.

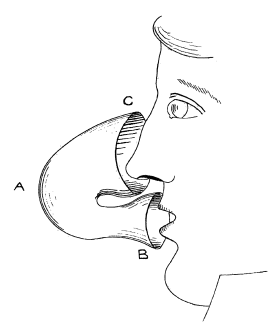

The police elected to try something new. One of their number, 23-year-old John A. Larson, had been experimenting with a lie-detecting device that measured a subject’s respiration, blood pressure, and other physical reactions as she responded to a series of questions. He asked the women’s consent to use the device in his investigation, and they agreed.

He started with Margaret Taylor, the student who had first reported the thefts. Part of his technique was to engage in preliminary small talk with the subject, to put her at ease. He found Taylor intelligent and witty, and she said she found his work fascinating and admired his ambition. She passed the test easily, showing no response to key terms such as crime, locker, or purse among Larson’s questions.

In reviewing the results, Larson realized that he might not have eliminated all the extraneous factors that could have affected the young women’s responses — he had tried to make them comfortable with the machine, but some of them also “might have been reacting to the questioner, not the questions.” So he called back Margaret Taylor to test this proposition. He connected her to the machine again and asked her to lie to him. Then he asked her out.

The two were married a year later. One of Larson’s assistants said, “It was an odd way to begin a romance.” The dorm thief was discovered among the other women, and Margaret recovered a $400 diamond ring she had lost. Today Larson is remembered as the father of the polygraph.

In recounting this story in his 2009 book The Lie Detectors, Ken Alder writes:

“Years later, he still had the record of their first meeting in his files, the zigzag trace of her heart as he asked her, ‘Are you interested in this test?'”