Math Notes

Prove that log10 5 is irrational.

Second Chances

A man was hanged who had cut his throat, but who had been brought back to life. They hanged him for suicide. The doctor had warned them that it was impossible to hang him as the throat would burst open and he would breathe through the aperture. They did not listen to his advice and hanged their man. The wound in the neck immediately opened and the man came back to life again although he was hanged. It took time to convoke the aldermen to decide the question of what was to be done. At length the aldermen assembled and bound up the neck below the wound until he died. O my Mary, what a crazy society and what a stupid civilization.

— Russian exile Nicholas Ogarev, writing to his English mistress Mary Sutherland, 1860, quoted in Alfred Alvarez, The Savage God: A Study of Suicide, 1971

In a Word

meridiation

n. a midday rest

Worth Remembering

William D. Harvey offered this in Omni in 1980 — a mnemonic for spelling mnemonics:

Mnemonics neatly eliminate man’s only nemesis: insufficient cerebral storage.

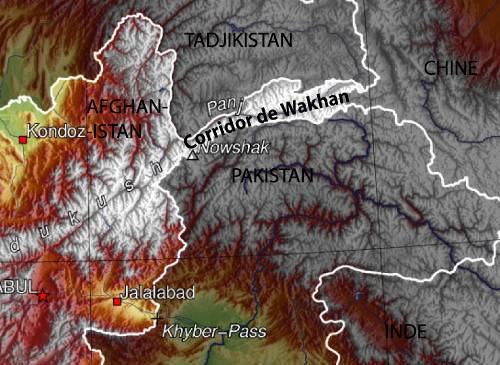

Neighbors

China and Afghanistan share a border. The Wakhan Corridor, a slender panhandle only 40 miles wide, reaches between Tajikistan and Pakistan to touch Afghanistan’s eastern border.

Because China does not use conventional time zones, that border requires the greatest time change of any international frontier — travelers must reset their watches by 3.5 hours.

Fast Forward

If a “dog year” is equivalent to seven human years, then time passes seven times more quickly for dogs than for humans. So in 1990 Rodney Metts invented a novelty watch that reflects this by advancing at seven times normal speed. This is a reminder as much to you as to your pet:

If a dog is kept locked in the basement of a house during an eight or nine hour day, for example, while its owner is away, the elapsed time on the dog watch will be 56 to 63 hours, or approximately two and one-half days. A one-hour ride in an automobile will register seven hours on a dog watch. Thus the value in dog time of a human activity will become quickly apparent.

That’s the actual patent figure. Part 10 is “dog.”

Giant Steps

In 1959 pianist Tommy Flanagan was living on 101st Street in Manhattan while John Coltrane lived on 103rd Street. “He came by my apartment with this piece, ‘Giant Steps.’ I guess he thought there was something different about it, because he sat down and played the changes. He said, ‘It’s no problem. I know you can do it, Maestro’ — which is what he called me. ‘If I can play this, you can.'”

If that sounds ominous, it was: The piece marked the culmination of the “Coltrane changes,” a sophisticated scheme of chord substitutions in which the root descends by major thirds, creating a much richer and more demanding harmonic landscape.

“There was no problem just looking at the changes,” Flanagan said. “But I didn’t realize he was going to play it at that tempo! There was no time to shed on it, there was no melody; it was just a set of chords, like we usually get. So we ran it down and we had maybe one take, because he played marvelous on everything. He was ready.”

“It still remains a heck of a document,” remembered drummer Arthur Taylor. “People all around the world look to that, and musicians also; that’s the thing. … John was very serious, like a magician too. He was serious and we just got down to the business at hand.”

First Things First

We [Einstein and Ernst Straus] had finished the preparation of a paper and were looking for a paper clip. After opening a lot of drawers we finally found one which turned out to be too badly bent for use. So we were looking for a tool to straighten it. Opening a lot more drawers we came upon a whole box of unused paper clips. Einstein immediately started to shape one of them into a tool to straighten the bent one. When asked what he was doing, he said, ‘Once I am set on a goal, it becomes difficult to deflect me.’

— Ernst Straus, “Memoir,” in A.P. French, ed., Einstein: A Centenary Volume, 1979

(Einstein said to an assistant at Princeton that this was the most characteristic anecdote that could be told of him.)

Podcast Episode 4: Mystery Airships, Marauding Lions, and Nancy Drew

In 1896 a strange wave of airship sightings swept Northern California; the reports of strange lights in the sky created a sensation that would briefly engulf the rest of the country. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll examine some of the highlights of this early “UFO” craze, including the mysterious role of a San Francisco attorney who claimed to have the answer to it all.

We’ll also examine the surprising role played by modern art in disguising World War I merchant ships and modern cars, discover unexpected lions in central Illinois and southern England, and present the next Futility Closet Challenge.