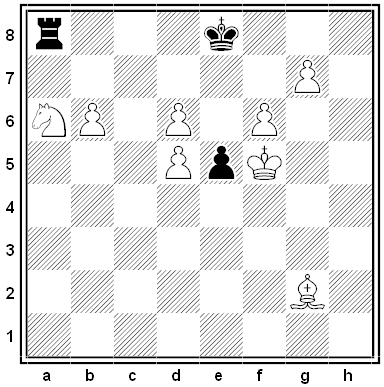

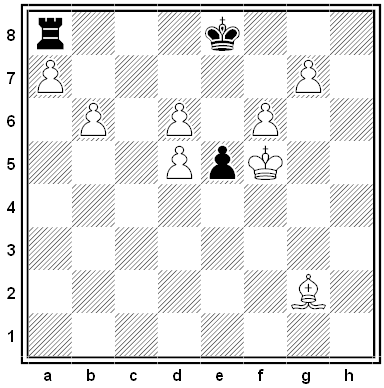

Raymond Smullyan presented this oddity in his Chess Mysteries of Sherlock Holmes in 1980. Suppose we come upon this abandoned chess game. Can White mate in two moves? The answer seems to be yes. If Black can’t castle, then White can play 1. Ke6 and then promote his g-pawn, giving mate. If Black can castle, that means that neither his king nor his rook has yet moved, and hence he must just have moved his pawn to e5. That permits White to capture the pawn en passant. Now if Black castles then 2. b7 is mate, and if he plays any other move then the g-pawn promotes. Either way, White mates Black on his second move.

But that’s odd. We’ve decided that a mate in two exists, but we can’t show it — and we don’t even know how White commences!

(F. Alexander Norman, “Classicists and Constructivists: A Dilemma,” Mathematics Magazine 62:5 [December 1989], 340-342. See Donkey Sentences.)

02/17/2025 UPDATE: Reader Eugene Kruglov points out that 1. Ke6 works in Smullyan’s position whether or not Black castles — if he does, then 2. a8=Q is mate. The position below works as Smullyan intended — when Black castles, only the en passant capture leads to mate in two. (Thanks, Eugene.)