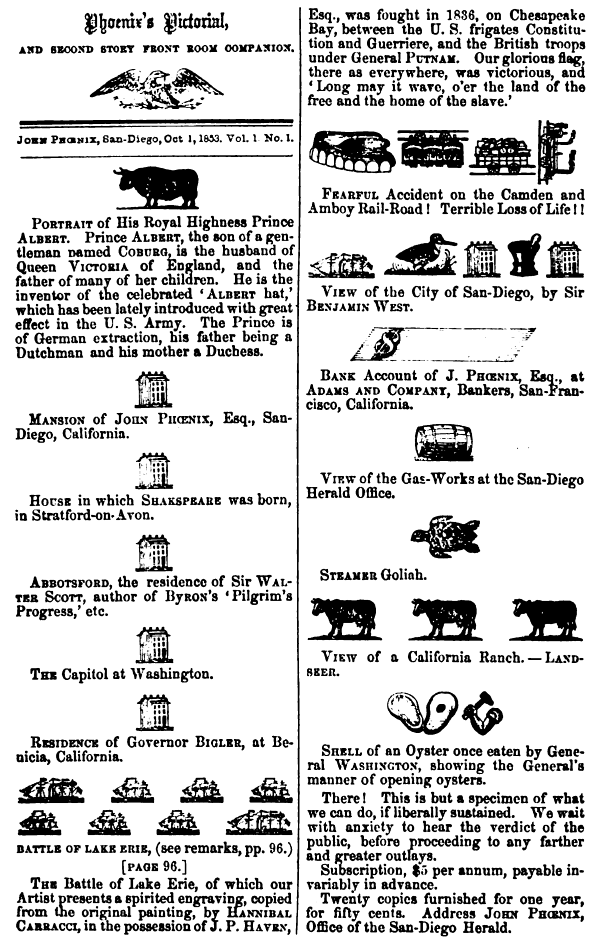

In 1962 mycologist R.W.G. Dennis reported a new species of fungus he had observed growing in Lancashire and East Africa. He called it Golfballia ambusta:

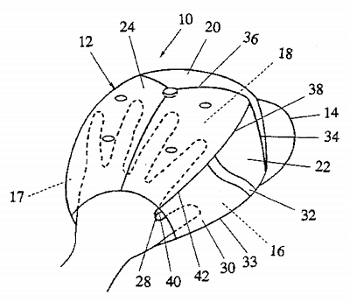

The unopened fruit body evidently closely resembles certain small, hard but elastic, spheres employed by the Caledonians in certain tribal rites, practised at all seasons of the year in enclosures of partially mown grass set apart for the purpose. The diameter of the volva is approximately 3 cm., its surface smooth or regularly furrowed, becoming much wrinkled after dehiscence, its texture extremely hard and tough. A gelatinous stratum, so characteristic of other phalloids, is wanting. The appearance and texture of the immature gleba is still unknown but at maturity it is extruded as a column, thickly set with short strap-like processes of an elastic consistency, each scarcely 1 cm. long and 1.5 mm. wide, abruptly truncated at the free end. As with other phalloids, there is a strong and distinctive odour, in this instance not unpleasant and identified independently by several observers as reminiscent of old or heated india-rubber. This is probably a reliable and important diagnostic character. Taste not recorded but probably mild; the fruit bodies are unlikely to be toxic but may well prove inedible from their texture. Spores have not been recovered and the means of reproduction therefore remains unknown.

It seems to be very prolific in America as well.

(R.W.G. Dennis. A remarkable new genus of phalloid in Lancashire and East Africa, Journ. Kew Guild. 8, 67 (1962): 181-182.)