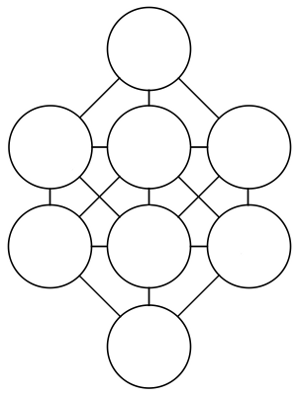

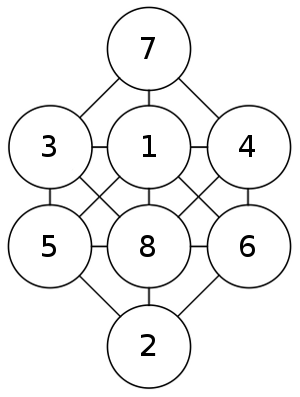

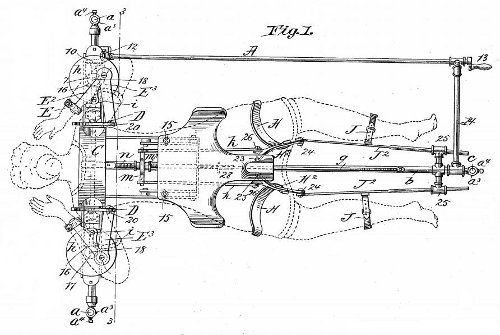

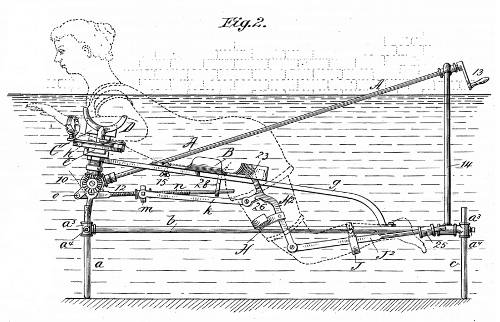

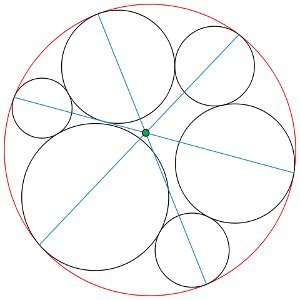

Thomas Jefferson, already absurdly accomplished by 1795, somehow found time to delve into cryptography, where he devised this cipher system. The letters of the alphabet are printed along the rim of each of 36 disks, which are stacked on an axle. One party rotates the disks until his message can be read along one of the 26 rows of letters, somewhat like a modern cylindrical bike lock. Now he can record the letters in any one of the other 25 rows and send that string safely to another party, who decodes it by reversing this procedure. If the message is intercepted, it’s useless even to someone who has the disks, because he must also know the order in which to stack them, and 36 disks can be stacked in 371,993,326,789,901,217,467,999,448,150,835, 200,000,000 different ways.

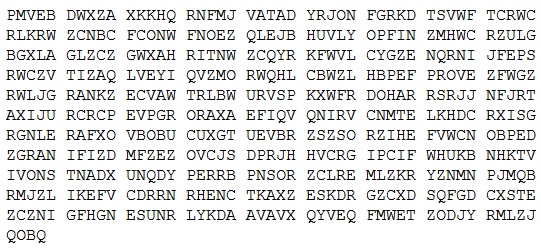

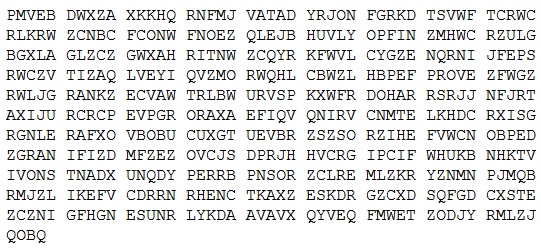

This is pretty robust. The cipher below, created in 1915 by U.S. Army cryptographer Joseph Mauborgne, has never been solved. “The known systems from this year (or earlier) shouldn’t be too hard to crack with modern attacks and technology,” writes NSA cryptologist Craig P. Bauer. “So, why don’t we have a plaintext yet? My best guess is that it used a cipher wheel” like Jefferson’s.

(L. Kruh, “A 77-year-old challenge cipher,” Cryptologia, 17(2), 172-174, 1993, quoted in Bauer’s Secret History: The Story of Cryptology, 2013.)