plagose

adj. fond of flogging

baculine

adj. pertaining to punishment by flogging

mastigophorous

adj. carrying a whip

plagose

adj. fond of flogging

baculine

adj. pertaining to punishment by flogging

mastigophorous

adj. carrying a whip

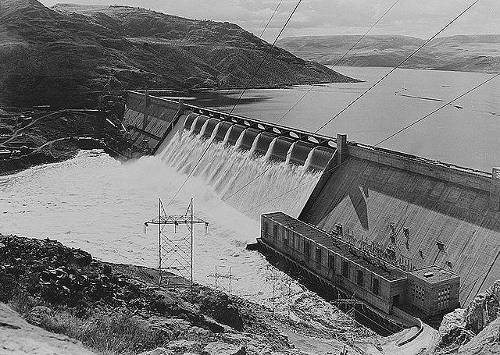

Shortly after the completion of Washington’s Grand Coulee Dam in 1942, engineers faced a difficult challenge: how to feed a cable through a 24-inch drain, two-thirds filled with grout, that wound 500 feet through the galleries inside the huge concrete structure.

The workers were stumped at first, but they hit on a novel solution. “An alley cat, raised on scraps from the construction men’s lunch pails, was summoned and one end of the 500-foot string was tied onto his tail,” reported the Spokane Daily Chronicle. “He was placed inside the drain, and an air hose was turned on to ‘encourage’ him to go forward.

“The feline scampered through the drain and was caught emerging at the other end, where he was freed. From then on it was a simple matter to tie a rope onto the string and then the cable and draw it through the drain.”

Physicist R.W. Wood had hit on the same technique 30 years earlier.

Pedro Carolino thought he was doing the world a favor in 1883 when he published English As She Is Spoke, ostensibly a Portuguese-English phrasebook. The trouble is that Carolino didn’t speak English — apparently he had taken an existing Portuguese-French phrasebook and mechanically translated the French to English using a dictionary, assuming that this would produce proper English. It didn’t:

It must to get in the corn.

He burns one’s self the brains.

He not tooks so near.

He make to weep the room.

I should eat a piece of some thing.

I took off him of perplexity.

I dead myself in envy to see her.

The sun glisten?

The thunderbolt is falling down.

Whole to agree one’s perfectly.

Yours parents does exist yet?

A dialogue with a bookseller:

What is there in new’s litterature?

Little or almost nothing, it not appears any thing of note.

And yet one imprint many deal.

That is true; but what it is imprinted. Some news papers, pamphlets, and others ephemiral pieces: here is.

But why, you and another book seller, you does not to imprint some good works?

There is a reason for that, it is that you canot to sell its. The actual-liking of the public is depraved they does not read who for to amuse one’s self ant but to instruct one’s.

But the letter’s men who cultivate the arts and the sciences they can’t to pass without the books.

A little learneds are happies enough for to may to satisfy their fancies on the literature.

An anecdote:

One eyed was laied against a man which had good eyes that he saw better than him. The party was accepted. “I had gain, over said the one eyed; why I see you two eyes, and you not look me who one.”

Proverbs:

The walls have hearsay.

Nothing some money, nothing of Swiss.

He has a good beak.

The dress don’t make the monk.

They shurt him the doar in the face.

Every where the stones are hards.

Burn the politeness.

To live in a small cleanness point.

To craunch the marmoset.

Mark Twain wrote, “In this world of uncertainties, there is, at any rate, one thing which may be pretty confidently set down as a certainty: and that is, that this celebrated little phrase-book will never die while the English language lasts. … Whatsoever is perfect in its kind, in literature, is imperishable: nobody can add to the absurdity of this book, nobody can imitate it successfully, nobody can hope to produce its fellow; it is perfect, it must and will stand alone: its immortality is secure.”

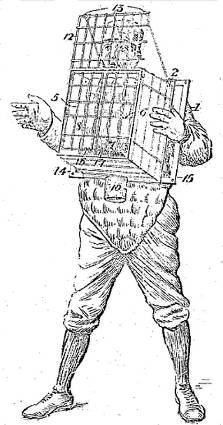

Illinois inventor James E. Bennett offered this contraption in 1904 to enable baseball catchers to intercept the ball without using their hands. The ball passes through the wire frame and hits a cushion at the rear of the box, then drops into a pocket from which the player can retrieve it.

It was not well received. The Cincinnati Enquirer said the box resembled “a cage built for a homesick bear or a dyspeptic hyena.”

Further, as Dan Gutman points out in his 1995 collection of baseball inventions, Banana Bats & Ding-Dong Balls, a catcher does more than catch pitches. “On a high pop, presumably, the catcher would have to run to the spot where he judged the ball was going to land, then lie on the ground face up and wait for it to hit him in the stomach.” At least his hands will be free.

In 2011 M.V. Berry et al. published “Can apparent superluminal neutrino speeds be explained as a quantum weak measurement?” in Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical.

The abstract read “Probably not.”

In 1978 John C. Doyle published “Guaranteed margins for LQG regulators” in IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control.

The abstract read “There are none.”

(Thanks, Dre.)

In 1972 the Toronto Society for Psychical Research set out to create a ghost. They invented a character named Philip, an English nobleman from the 17th century, and tried to contact him through sittings in which they discussed his life, to see whether they could induce a “collective hallucination.”

When a year of this produced no results, they adopted the trappings of a more formal séance, introducing colored lights, singing songs, and reciting poetry while trying to conjure Philip’s spirit. After three or four of these sessions, surprisingly, “the group felt a vibration within the table top, somewhat like a knock or rap.”

Philip had, apparently, shown up. After some initial confusion, the group established a convention by which he could express himself — one rap meant yes, two meant no. And he was quite willing to talk:

‘Did you have your own regiment?’ Sid asked.

(Rap) ‘Yes.’

‘Were you wounded in the fighting?’

(Rap, rap) ‘No.’

‘I wonder which battles he fought in,’ Lorne asked. ‘Philip, did you fight at Naseby?’

(Rap, rap) ‘No.’

‘Did you fight at Marston Moor?’

(Rap) ‘Yes.’

‘I wonder what weapons they used?’ Al asked. ‘Did you use pikemen?’

(Rap) ‘Yes.’

‘Would they have had guns of any kind then?’ someone asked.

‘They would have had muskets,’ Lorne said.

(Immediate confirmatory rap) ‘Yes.’

That’s from Conjuring Up Philip, a 1976 account by Iris Owen, a member of the group. With time the rappings grew stronger, and the table would occasionally move around the room and even levitate. Owen wrote, “In addition to sliding across the floor (which incidentally was covered with a thick pile carpet), the table would tilt in various ways, lifting one, two, or three legs, and pivot, sometimes almost dancing.”

It’s hard to know what to make of this. On the one hand, most of Philip’s verbal communications were simply those that the group expected to receive. For example, he said that Charles I had loved cats but not horses or dogs; this isn’t historically accurate, but the questioner was a cat lover. Owen called Philip “a composite of [the group’s] own invented imaginations … a character born of their own desire to bring him as much to actuality as they could.”

But the physical tricks are harder to understand. The simplest explanation is that some in the group were deliberately creating the “supernatural” effects, a possibility that all strongly denied. Or perhaps the group really had stumbled into some sort of collective, or wishful, hallucination. Whatever the case, the whole episode shows that even supernatural explorations that are known to be groundless can produce convincingly “otherworldly” effects for a receptive audience. To that extent, Philip was a ghost who helped to disprove his own existence.

A bottle of fine wine normally improves with age for a while, but then goes bad. Consider, however, a bottle of EverBetter Wine, which continues to get better forever. When should we drink it?

— John L. Pollock, “How Do You Maximize Expectation Value?”, Noûs, September 1983

See The Devil’s Game.

Several spherical planets of equal size are floating in space. The surface of each planet includes a region that is invisible from the other planets. Prove that the sum of these regions is equal to the surface area of one planet.

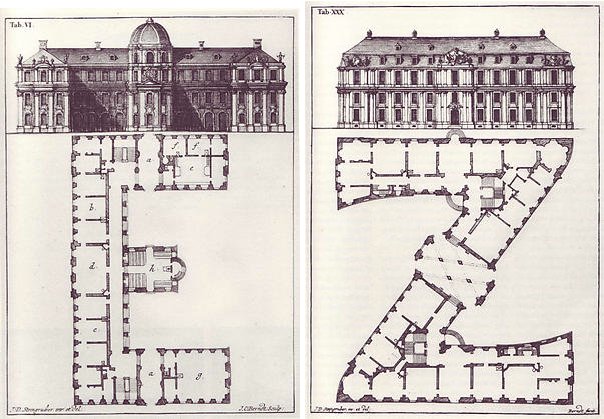

Johann David Steingruber fulfilled his literary ambitions on a drafting table — his Architectural Alphabet (1773) renders each letter of the alphabet as the floor plan of a palace.

Antonio Basoli’s Alfabeto Pittorico (1839) presents the letters as architectural drawings:

Perhaps next we can actually build them.

“It is the law of life that if you are kind to someone you feel happy. If you are cruel you are unhappy. And if you hurt someone, you will be hurt back.” — Cary Grant

“When I do good, I feel good. When I do bad, I feel bad. That’s my religion.” — Abraham Lincoln

“It all comes to this: the simplest way to be happy is to do good.” — Helen Keller