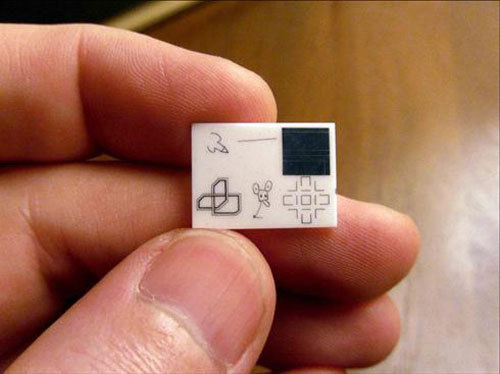

There’s a museum on the moon. As Apollo 12 prepared to depart in 1969, New York sculptor Forrest Myers commissioned drawings from six prominent artists and had them engraved on a ceramic wafer, then arranged for a Grumman engineer to smuggle it onto the lunar lander.

Two days before launch he received a telegram confirming that the engineer had been successful. If he was, then the tiny museum is still up there, bearing drawings by Robert Rauschenberg, David Novros, John Chamberlain, Claes Oldenburg, Forrest Myers, and Andy Warhol. Perhaps they’ll attract some patrons.