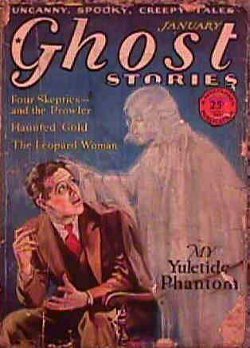

Why do ghosts wear clothes? If a ghost is the spirit of a living creature, how can it carry its inanimate garments into the afterlife?

“How do you account for the ghosts’ clothes — are they ghosts, too?” asked the Saturday Review in 1856. “What an idea, indeed! All the socks that never came home from the wash, all the boots and shoes which we left behind us worn out at watering-places, all the old hats which we gave to crossing-sweepers … What a notion of heaven — an illimitable old clothes-shop, peopled by bores, and not a little infested with knaves!”

In 1906 psychic researcher Andrew Lang argued that, far from confusing the notion of an afterlife, ghosts’ clothing might even help to corroborate its existence. “A pretty instance occurs, I think, in a biography of Warren Hastings. The anecdote, as I remember it, avers that at a meeting of the Council of the East India Company in Calcutta one of the members (I think several shared the experience) saw his own father, wearing a hat of a peculiar shape, hitherto strange to the observers. In due time came a ship from London bearing news of the father’s death, and a large and well-selected assortment of the new hat fashionable in England. It was the hat worn by the paternal appearance! If the circumstances are recorded in the minutes of the proceedings of the Council, which I have not consulted, then the hat of that spook becomes important as evidence.”

Even if we grant that a dead person can convey his most personal belongings into the afterlife, how are we to account for phantom ships, coaches, and railway trains? In his 1879 book The Spirit World, American spiritualist Eugene Crowell decided that, rather than being the spirits of “dead” earthly conveyances, these are constructed in the afterlife by the ghosts of mariners and railwaymen who want to ply their trades again. Spectral ships “glide over the waves without sinking,” Crowell explained, “and earthly winds propel them at rates of speed which our ships cannot attain.” If that’s true, then perhaps some ghostly tailor is simply manufacturing clothes for the naked spirits of the newly dead. Decent of him.