If I buy two toothbrushes in a “buy one, get one free” offer … which one did I buy, and which was free?

(From philosopher Roy Sorensen.)

If I buy two toothbrushes in a “buy one, get one free” offer … which one did I buy, and which was free?

(From philosopher Roy Sorensen.)

While Paulet St. John, Esq., was fox hunting in September 1733, his horse plunged into a chalk pit 25 feet deep. The horse survived and went on to win the Hunters’ Stakes at Winchester the following year.

St. John was so impressed that he erected a monument on Farley Mount, where it stands to this day.

He named the horse “Beware Chalk Pit.”

A clever Toronto lawyer was deep into a technical argument before the Supreme Court. His position was dependent upon a close reading of the legal text and turned on the letter of the law. Suddenly the chief justice, Beverley McLachlin, leaned forward and asked the counsel if his argument also worked in French. After all, the law is the law in both languages and a loophole in one tends to evaporate in the other. Only an argument of substance stands up. The lawyer had no idea what to reply.

— John Ralston Saul, A Fair Country, 2008

How long is a coastline? If we measure with a long yardstick, we get one answer, but as we shorten the scale the total length goes up. For certain mathematical shapes, indeed, it goes up without limit.

English mathematician Lewis Fry Richardson discovered this perplexing result in the early 20th century while examining the relationship between the lengths of national boundaries and the likelihood of war. If the Spanish claim that the length of their border with Portugal is 987 km, and the Portuguese say it’s 1,214 km, who’s right? The ambiguity arises because a wiggly boundary occupies a fractional dimension — it’s something between a line and a surface.

“At one extreme, D = 1.00 for a frontier that looks straight on the map,” Richardson wrote. “For the other extreme, the west coast of Britain was selected because it looks like one of the most irregular in the world; it was found to give D = 1.25.”

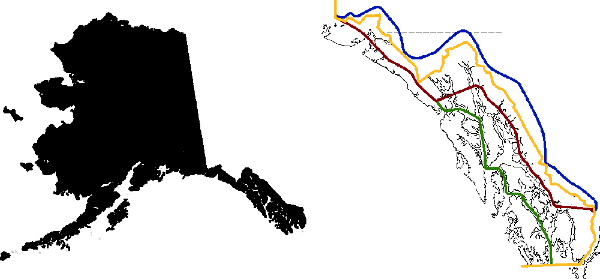

This is a mathematical notion, but it’s also a practical problem. On the fjord-addled panhandle of Alaska, the boundary with British Columbia was originally defined as “formed by a line parallel to the winding of the coast.” Who gets to define that? On the map below, the United States claimed the blue border, Canada wanted the red one, and British Columbia claimed the green. The yellow border was arbitrated in 1903.

“Life is like playing a violin solo in public and learning the instrument as one goes on.” — Samuel Butler

“Life is like riding a bicycle. To keep your balance you must keep moving.” — Albert Einstein

“Life is not having been told that the man has just waxed the floor.” — Ogden Nash

“You cannot learn to skate without making yourself ridiculous — the ice of life is slippery.” — George Bernard Shaw (quoting the motto of the Cambridge Fabian Society)

In April 1819 the French slave ship Rodeur set sail for Guadeloupe from the Bight of Biafra with a crew of 22 men and 162 slaves. After 15 days, a disease of the eyes appeared among the slaves in the hold. The heartless captain threw 36 slaves overboard, but the illness soon spread to the crew, and eventually everyone on board except for a single man was blind.

And then came one of the most remarkable incidents in the history of sea commerce. As the Rodeur was crawling along with this one man at the helm, another ship, with all sails set, was seen. That was a glad moment on the Rodeur, and she was quickly headed for the stranger, hoping to get men who could navigate the ship. Drawing near, the Rodeur’s lone helmsman observed that the stranger was steering wildly, and that no one could be seen on board. But the moment the Rodeur had arrived within hailing distance men came to the stranger’s rail, and in frantic tones said that every one on board had become blind, and begged for the help that the Rodeur had come to secure. The stranger was the Spanish slaver Leon.

That’s from journalist John Randolph Spears, who wrote a history of the American slave trade at the turn of the century. This is such a horrible story that I hoped it was just folklore, but it’s borne out in the inquiries that followed and commemorated in John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem “The Slave-Ships”:

“Help us! for we are stricken

With blindness every one;

Ten days we’ve floated fearfully,

Unnoting star or sun.

Our ship’s the slaver Leon,–

We’ve but a score on board;

Our slaves are all gone over,–

Help, for the love of God!”

On livid brows of agony

The broad red lightning shone;

But the roar of wind and thunder

Stifled the answering groan;

Wailed from the broken waters

A last despairing cry,

As, kindling in the stormy light,

The stranger ship went by.

Unable to help one another, the two ships parted. On June 21 the Rodeur reached Guadaloupe, where the last man went blind. The Leon passed into the Atlantic and was never seen again.

On Sept. 1, 1939, a flock of 850 sheep were bedded down for the night in Pine Canyon in the Raft River Mountains of northwestern Utah when a passing thunderstorm wet both the ground and the animals. A single stroke of lightning killed 835 sheep, 98 percent of the flock.

Similarly (below), two bolts of lightning killed 654 sheep on Mill Canyon Peak in the American Fork Canyon in north-central Utah on July 18, 1918.

So avoid northern Utah. On the other hand:

A ploughman in a field, Reuben Stephenson, of Langtoft, England, was struck down by lightning, when both his horses were killed on the spot, and he was so much injured that his life was at first despaired of. In consequence of the accident, Dr. Allison of Birdlington, attended upon the man, and whilst doing so, found he was suffering from a malignant cancer of the lip. When Mr. Stephenson had sufficiently recovered from the effects of the lightning, an arrangement was entered into for the removal of the cancer by an operation; but, strange to say, just when this was on the point of being performed, a minute inspection was made of the cancer, when it was discovered that from the time of the accident, a healing process had been commenced in the lip; this being so evident, the operation was, of course, not attempted; and, in a moderate space of time, the man was completely cured.

— Lancet, 1855, quoted in Paul Fitzsimmons Eve, A Collection of Remarkable Cases in Surgery, 1857

periplus

n. a circumnavigation, an epic journey, an odyssey

In 1505 Ferdinand Magellan sailed east to Malaysia, where he acquired a slave named Enrique who accompanied him on his subsequent westward circumnavigation of the globe. When that expedition reached the Philippines, Enrique escaped, and his fate is lost to history. That’s intriguing: If he managed to travel the few hundred remaining miles to his homeland, then he was the first person in history to circumnavigate the earth.

Suppose we have a clock whose hour and minute hands are identical. How times times per day will we find it impossible to tell the time, provided we always know whether it’s a.m. or p.m.?