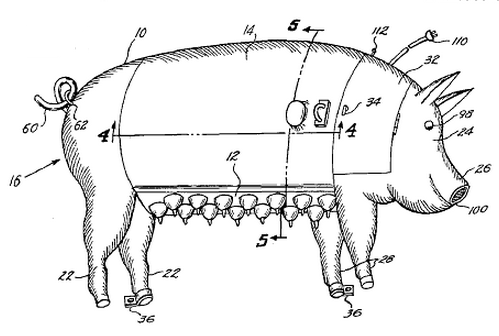

How do you feed newborn pigs when the mother has died or when they are so small or numerous that they may be crushed at feeding time? In 1961 Cora Lee Brown found a unique solution:

One of the important objects of this invention is the provision of a pig feeder designed in the form and size of an actual sow so as to simulate as much as possible the nursing environment afforded by the real animal and to thereby create a natural atmosphere for cultivating the natural eating habits and conditions of the newborn pigs.

In field tests Brown’s invention reduced the mortality rate of newborn pigs. It even plays a recording of the actual sounds of a sow at feeding time, “which operates on predetermined time schedules and is synchronized with the regulated supply of feed to the feeding tank.”