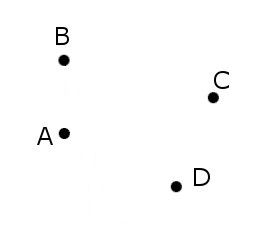

A “coffin,” or killer problem, from the oral entrance exams to the math department of Moscow State University:

Construct (with ruler and compass) a square given one point from each side.

A “coffin,” or killer problem, from the oral entrance exams to the math department of Moscow State University:

Construct (with ruler and compass) a square given one point from each side.

In a 1965 story on the accidental death of a local millworker, Charlotte News police reporter Joseph Flanders wrote, “It was as if an occult hand had reached down from above and moved the players like pawns upon some giant chessboard.”

This struck Flanders’ fellow reporters as hilariously purple, and they founded the Order of the Occult Hand to immortalize him by sneaking the phrase into as many stories as possible. This has evolved into an in-joke among American journalists:

“It’s a phrase that has that sense of journalese about it, sort of a campy phrase,” Greenberg told James Janega of the Chicago Tribune in 2004. He holds a Pulitzer and has used the phrase at least six times, “just to keep my standing in good order.”

But Montgomery told Janega that in the modern era the occult hand might be coming to an end. “There’s so much bad writing and so much pretentious writing,” he said, “I’m afraid it would get lost.”

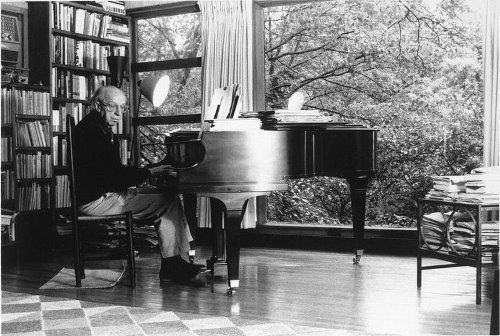

“The whole problem can be stated quite simply by asking, ‘Is there a meaning to music?’ My answer would be, ‘Yes.’ And ‘Can you state in so many words what the meaning is?’ My answer to that would be, ‘No.'” — Aaron Copland, What to Listen for in Music, 1939

A singer sings this song:

I’m a stockman to my trade, and they call me Ugly Dave.

I’m old and gray and only got one eye.

In a yard I’m good, of course, but just put me on a horse,

And I’ll go where lots of young-uns daren’t try.

He goes on to brag of his skill in riding, whipping, branding, shearing: “In fact, I’m duke of every blasted thing.”

There are two fictions here: The singer is pretending to be Ugly Dave, and Ugly Dave is telling boastful lies. But why doesn’t this collapse? How are we able to tell that the fictional Ugly Dave is lying (which is essential to the song’s meaning), rather than telling the truth?

“We must distinguish pretending to pretend from really pretending,” writes David Lewis in Philosophical Papers. “Intuitively it seems that we can make this distinction, but how is it to be analyzed?”

Letter from Eddie Cantor to Groucho Marx, Jan. 9, 1964:

Dear Julius,

Since being inactive as a performer I’ve done quite a bit of scribbling. This is my fourth year writing a column for Diners’ Club Magazine.

Will you please send me as quick as you can two lines which have brought you the biggest laughs. I would appreciate it for my next column.

Gratefully,

Eddie

Groucho responded:

Dear Eddie:

Briefly (and quickly) the two biggest laughs that I can recall (other than my three marriages) were in a vaudeville act called “Home Again.”

One was when Zeppo came out from the wings and announced, ‘Dad, the garbage man is here.’ I replied, ‘Tell him we don’t want any.’

The other was when Chico shook hands with me and said, ‘I would like to say good-bye to your wife,’ and I said, ‘Who wouldn’t?’

Take care of yourself.

Regards,

Groucho Marx

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vpl-Pj6sWmI

Siren Elise Wilhelmsen taught a clock to knit a scarf. The mechanism’s progress is reflected on its face, which functions as a 24-hour clock; it adds one stitch per hour and one segment per day, producing a wearable two-meter scarf in a year.

“What I wanted to show was the nature of time in a different way,” the Norwegian designer says. The clock does this in three ways: The unknitted skein represents time to come, the clock itself displays the current time, and the finished scarf represents time past.

Unused titles from Raymond Chandler’s notebooks:

The Man with the Shredded Ear

All Guns Are Loaded

The Man Who Loved the Rain

The Corpse Came in Person

The Porter Rose at Dawn

We All Liked Al

Too Late for Smiling

They Only Murdered Him Once

The Diary of a Loud Check Suit

Stop Screaming — It’s Me

Return from Ruin

Between Two Liars

The Lady with the Truck

They Still Come Honest

My Best to the Bride

Law Is Where You Buy It

Deceased When Last Seen

The Black-Eyed Blonde

Chandler delighted in titles. In a 1954 letter to Hamish Hamilton, he invented a “neglected author” named Aaron Klopstein who “committed suicide at the age of 33 in Greenwich Village by shooting himself with an Amazonian blow gun, having published two novels entitled Once More the Cicatrice and The Sea Gull Has No Friends, two volumes of poetry, The Hydraulic Face Lift and Cat Hairs in the Custard, one book of short stories called Twenty Inches of Monkey, and a book of critical essays entitled Shakespeare in Baby Talk.”

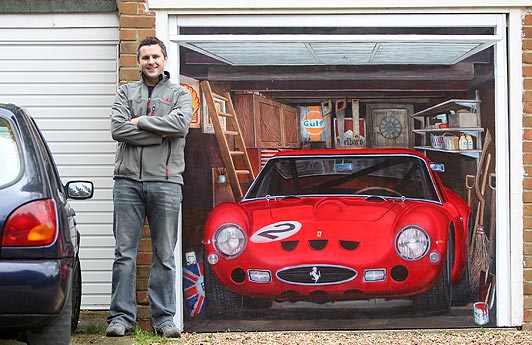

The Ferrari 250 GTO has been called the top sports car of all time. Only 39 were manufactured, so they sell for as much as $35 million among collectors.

Chris Smart of Bishopstoke, Hampshire, couldn’t afford to buy one …

… so he painted one on his garage door.

You’re about to play a game. A single person enters a room and two dice are rolled. If the result is double sixes, he is shot. Otherwise he leaves the room and nine new players enter. Again the dice are rolled, and if the result is double sixes, all nine are shot. If not, they leave and 90 new players enter.

And so on, the number of players increasing tenfold with each round. The game continues until double sixes are rolled and a group is executed, which is certain to happen eventually. The room is infinitely large, and there’s an infinite supply of players.

If you’re selected to enter the room, how worried should you be? Not particularly: Your chance of dying is only 1 in 36.

Later your mother learns that you entered the room. How worried should she be? Extremely: About 90 percent of the people who played this game were shot.

What does your mother know that you don’t? Or vice versa?

(Paul Bartha and Christopher Hitchcock, “The Shooting Room Paradox and Conditionalizing on Measurably Challenged Sets,” Synthese, March 1999)

(Thanks, Zach.)

philologaster

n. an incompetent philologist

nitigram

n. a second-rate epigram

cacography

n. poor spelling