In 1967 Luis d’Antin Van Rooten published Mots D’Heures: Gousses, Rames, a collection of French poems that make little sense until you read them aloud:

Oh, les mots d’heureux bardes

Où en toutes heures que partent.

Tous guetteurs pour dock à Beaune.

Besoin gigot d’air

De que paroisse paire.

Et ne pour dock, pet-de-nonne.

Et qui rit des curés d’Oc?

De Meuse raines, houp! de cloques.

De quelles loques ce turque coin.

Et ne d’ânes ni rennes,

Écuries des curés d’Oc.

In 1980 Ormonde de Kay met this with N’Heures Souris Rames:

Très bel aï n’ de maïs

Si à Oudh héronne.

Des Halles Roi Naphte de phare mer soif

Chicot taffetas tel suite de carvi naïf.

Didier voyou si sachée saille t’ignore l’aï

Fesse très bel aï n’ de maïs.

Rabais dab dab

Trille, ménine, taupe.

Hindou d’yeux tines, que débit?

Débouchoir du bécarre

De canne d’élastique maigre.

Trop d’émaux, nefs alterés.

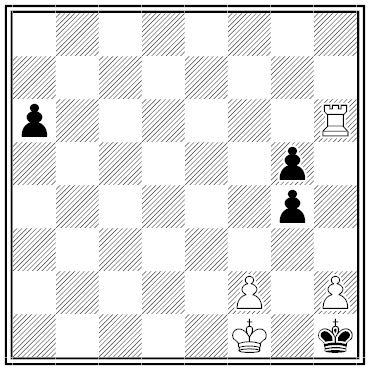

And in 1981 John Hulme expanded into German with Mörder Guss Reims:

Schach an Schill! Wend’ ab die Hilde —

Fesch Appel, oh Worte!

Schachfell Daunen, Brockensgrauen,

Und Schill Keim Tuümpel in Naphtha.

Pater keck, Pater keck, Bechers Mann.

Bigamie er keck es Festeschuh kann.

Batet und Brikett und Marktwitwe Tie

Und Butter, Tinte offen fort Omi Anämie.

Um die Dumm’ die Saturn Aval;

Um die Dumm’ die Ader Grät’ fahl.

Alter ging’s Ohr säss und Alter ging’s mähen.

Kuh denn “putt” um Dieter Gitter er gähn.

“In this lively allegorical poem a foolish Greek maiden becomes embroiled with the supernatural and is rescued in the nick of time from a fate worse than immortality by being turned into a cow.”

See also “It Means Just What I Choose It to Mean” and Read It Aloud.

(I think de Kay is the same fellow who proposed the theory of continental drip — a very playful man!)