vecke

n. an old woman

graocracy

n. government by old women

vecke

n. an old woman

graocracy

n. government by old women

Extract from the log of A.H. Raymer, second officer of the S.S. Fort Salisbury, Oct. 28, 1902, quoted in The Zoologist, January 1903:

Dark object, with long, luminous trailing wake, thrown in relief by a phosphorescent sea, seen ahead, a little on starboard bow. Look-out reported two masthead lights ahead. These two lights, almost as bright as a steamer’s lights, appeared to shine from two points in line on the upper surface of the dark mass. Concluded dark mass was a whale, and lights phosphorescent. On drawing nearer, dark mass and lights sank below the surface. Prepared to examine the wake in passing with binoculars. Passed about forty to fifty yards on port side of wake, and discovered it was the scaled back of some huge monster slowly disappearing below the surface. Darkness of the night prevented determining its exact nature, but scales of apparently 1 ft. diameter, and dotted in places with barnacle growth, were plainly discernible. The breadth of the body showing above water tapered from about 80 ft. close abaft, where the dark mass had appeared to about 5 ft. at the extreme end visible. Length roughly about 500 ft. to 600 ft. Concluded that the dark mass first seen must have been the creature’s head. The swirl caused by the monster’s progress could be distinctly heard, and a strong odour like that of a low-tide beach on a summer day pervaded the air. Twice along its length the disturbance of the water and a broadening of the surrounding belt of phosphorus indicated the presence of huge fins in motion below the surface. The wet, shiny back of the monster was dotted with twinkling phosphorescent lights, and was encircled with a band of white phosphorescent sea. Such are the bare facts of the passing of the Sea Serpent in latitude 5 deg. 31 min. S., longitude 4 deg. 42 min. W., as seen by myself, being officer of the watch, and by the helmsman and look-out man.

The ship’s master added, “I can only say that he is very earnest on the subject, and certainly has, together with look-out and helmsman, seen something in the water of a huge nature as specified.”

Letter to the Times, Oct. 14, 1939:

Sir,

If ordinary English usage counts for anything, an evacuee is a person who has been evacued, whatever that may be, as a trustee is one who has been trusted; for ‘evacuee’ cannot be thought of as a feminine French form, as ’employee’ is by some.

Where are we going to stop if ‘evacuee’ is accepted as good English? Is a terrible time coming in which a woman, much dominated by her husband, will be called a dominee? Will she often be made a humiliee by his rough behavior and sometimes prostree with grief after an unsought quarrel?

Must sensitive people suffer the mutilation of their language until they die and are ready to become cremees?

I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

F.H.J. Newton

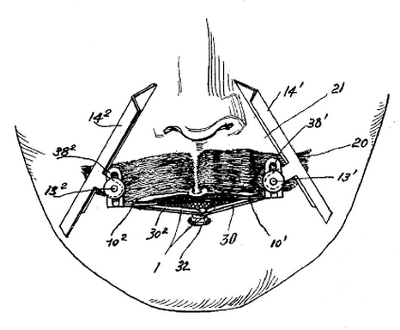

When one is a dashing French inventor one has little patience for clumsy mustache hygiene. This “apparatus for the cut of the mustache,” patented by Pierre Calmels in 1927, “gives the mustache the desired shape and automatically reproduces this shape without any possibility of error and without loss of time.” Adjust the guide once into the proper configuration and you can use it thereafter as a sort of stencil: Just hold the apparatus between your teeth and trim the whiskers to the designated length.

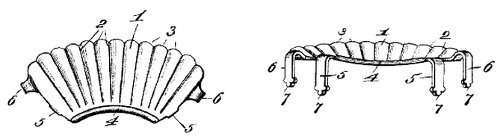

Edwin Green’s “design for a mustache-guard for cups,” below, was patented in 1898: The plate can be clamped to a teacup to keep one’s mustache dry. The idea was referenced a century later in a related invention — an “apparatus and system for covering and protecting the rim of a paint can.”

If it’s a sin to end a sentence with one preposition, then presumably it’s even worse to end it with two. How far can we take this? For the August 1968 issue of Word Ways: The Journal of Recreational Linguistics, Darryl Francis devised one sentence that ends with nine prepositions. If the Yardbirds’ 1966 single “Over, Under, Sideways, Down” were exported to Australia and then retrieved by a traveler, the question might be asked:

“What did he bring ‘Over, Under, Sideways, Down’ up from Down Under for?”

Inspired, Ralph Beaman pointed out that if this issue of the journal were now brought to a boy who slept on the upper floor of a lighthouse, he might ask:

“What did you bring me the magazine I didn’t want to be read to out of about ‘”Over Under, Sideways, Down” up from Down Under’ up around for?”

“This has a total of fifteen terminal prepositions,” writes Ross Eckler, “but the end is not in sight; for now the little boy can complain in similar vein about the reading material provided in this issue of Word Ways, adding a second ‘to out of about’ at the beginning and ‘up around for’ at the end of the preposition string. The mind boggles at the infinite regress which has now been established.”

feriation

n. the act of observing a holiday

A curious excerpt from The Pursuit of the Heiress, a history of aristocratic marriage in Ireland by A.P.W. Malcolmson, 2006:

Another strange tale, which this time ended less happily for the heir presumptive, is that of the 3rd Earl of Darnley, an eccentric bachelor who suffered from the delusion that he was a teapot. In 1766, when he was nearly fifty and had held the family title and estates for almost twenty years, Lord Darnley suddenly and unexpectedly married; and between 1766 and his death in 1781, he fathered at least seven children, in spite of his initial alarm that his spout would come off in the night.

I thought this couldn’t possibly be true, but Malcolmson gives two sources, a letter from the Rev. George Chinnery to Viscountess Midleton, Aug. 18, 1762, kept at the Surrey History Centre in Woking, and a typescript family history by Rear Admiral W.G.S. Tighe. An Irish auction house supports the story.

(Thanks, Donald.)

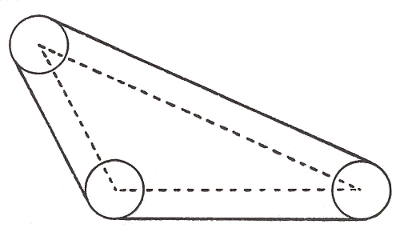

A puzzle by Harry Langman:

A thin belt is stretched around three pulleys, each of which is 2 feet in diameter. The distances between the centers of the pulleys are 6 feet, 9 feet, and 13 feet. How long is the belt?

I know a pilgrim from a distant land

Who said: Two vast and sawn-off limbs of quartz

Stand on an arid plain. Not far, in sand

Half sunk, I found a facial stump, drawn warts

And all; its curling lips of cold command

Show that its sculptor passions could portray

Which still outlast, stamp’d on unliving things,

A mocking hand that no constraint would sway:

And on its plinth this lordly boast is shown:

“Lo, I am Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, O Mighty, and bow down!”

‘Tis all that is intact. Around that crust

Of a colossal ruin, now windblown,

A sandstorm swirls and grinds it into dust.

(By Georges Perec, translated from the French by Gilbert Adair.)