Thomas Deininger makes assemblages of trash that take on new meaning when viewed from a particular angle — offering a new perspective on environmental degradation.

Thomas Deininger makes assemblages of trash that take on new meaning when viewed from a particular angle — offering a new perspective on environmental degradation.

Edmund Clerihew Bentley invented the clerihew, a distinctive biographical poem in four lines:

Sir Christopher Wren

Said, “I am going to dine with some men.

If anyone calls

Say I am designing St Paul’s.”

For The Complete Clerihews of E. Clerihew Bentley, Bentley compiled an “Index of Psychology, Mentality and Other Things Frequently Noted in Connection With Genius,” so that his readers might explore particular personality traits in the people he wrote about. To the poem above he assigned the following entries:

Atrocity

Bankruptcy, moral

Conduct, disingenuous

Domestic servants, dishonesty among, encouragement of

Escutcheon, blot on, action involving

Fact, cynical perversion of

Guile

Hypocrisy, calculated

Integrity, low standard of

Jesuitry

Knavery

Lie, bouncing circulation of

Machiavelli, unholy precepts of, tendency to act upon

Noblesse Oblige, disregard of apophthegm

Openness, want of

Principle, lack of

Quickening, spiritual, need of

Restoration, lax morality of, readiness to fall in with

Satanism, revolting display of

Turpitude

Untruth, plausible, ability to frame

Veracity, departure from

World, the next, neglect of prospects in

Y.M.C.A., unfitness for

Zion, outcast from

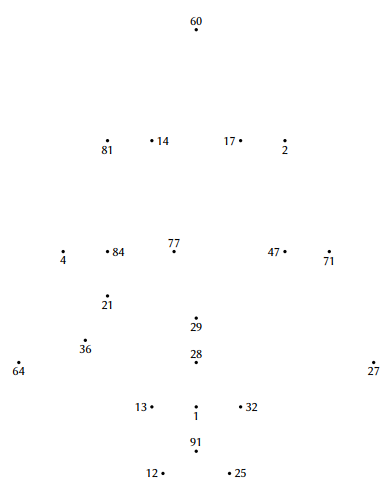

This year’s puzzle Christmas card from Chalkdust Magazine, designed by Matthew Scroggs, contains 10 puzzles. Answering them correctly will guide you in completing a Christmas-themed picture. Here’s a printable PDF.

And King William’s College has released its annual general knowledge quiz, which appears as fiendish as ever. (“During 1924, in what could one learn of the ordinariness of Chandrapore?”) MetaFilter is sponsoring a shared Google Sheet where solvers can collaborate; answers will appear on the Guardian website on January 15.

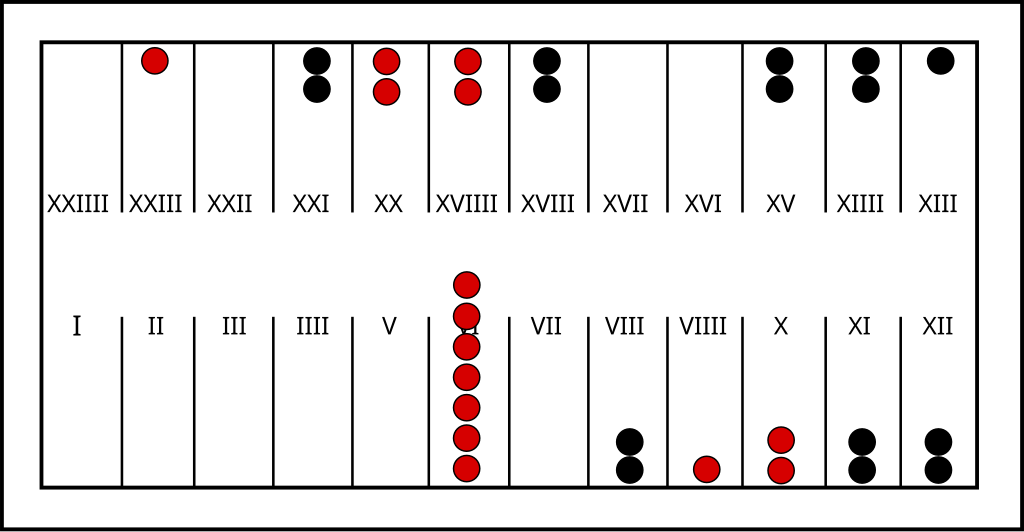

Playing tabula, a forerunner of backgammon, in 480 AD, the Byzantine emperor Zeno made such a stupendously unfortunate dice roll that we still remember it 1500 years later. Playing red in the position above, Zeno rolled a 2, 5, and 6. “As he was unable to move the men on (6) which were blocked by the black men on (8), (11), (12): or the singleton on (9), which was blocked by the black pieces on (11), (14), (15): he was forced to break up his three pairs, a piece from (20) going to (22), one from (19) going to (24), and one from (10) going to (16),” explained R.C. Bell in Board and Table Games From Many Civilizations (1960). “No other moves were possible and he was left with eight singletons and a ruined position.”

See Dice Shaming.

When the philosopher Antisthenes was being initiated into the mysteries of Orpheus, and the priest told him that those who vowed themselves to that religion were to receive after death eternal and perfect blessings, he said to him: ‘Why, then, do you not die yourself?’

— Montaigne, Apology for Raymond Sebond, 1576

The first nonhuman artist to be given her own art exhibition was a female pig rescued from a South African slaughterhouse in 2016. When her keeper, Joanne Lefson, noticed that the pig ate everything in her stall except some paintbrushes, she taught her to hold a brush in her mouth and apply paint to an easel, and Lefson could sell the resulting works to raise funds for the sanctuary.

Pigcasso’s works have been exhibited in the Netherlands, Germany, the United Kingdom, and China. In 2021 German collector Peter Esser paid £20,000 for her painting Wild and Free, a record price for an artwork created by an animal. Altogether the pig’s sales have raised more than $1 million. She died in March 2024, one day before Jane Goodall could arrive to meet her.

“Pleasant is the glittering of the sun today upon these margins because it flickers so.”

— An anonymous medieval monk writing in a manuscript of Cassiodorus, quoted in Nora Chadwick’s The Celts, 1971

One of the most beautiful and moving of the bird-songs heard throughout the country which [French merchant Nicolas] Denys governed [in 17th-century Acadia], is that of the Veery, or Wilson’s Thrush. The Maliseet Indians of the Saint John River, as Mr. Tappan Adney has recently told us, say this bird is calling Ta-né-li-ain′, Ni-kó-la Dĕn′-i Dĕn′-i?, that is, ‘Where are you going, Nicolas Denys?’ and Mr. Adney thinks this an actual echo from the days of our author.

— From William Francis Ganong’s 1908 introduction to Denys’ Description and Natural History of the Coasts of North America, 1672

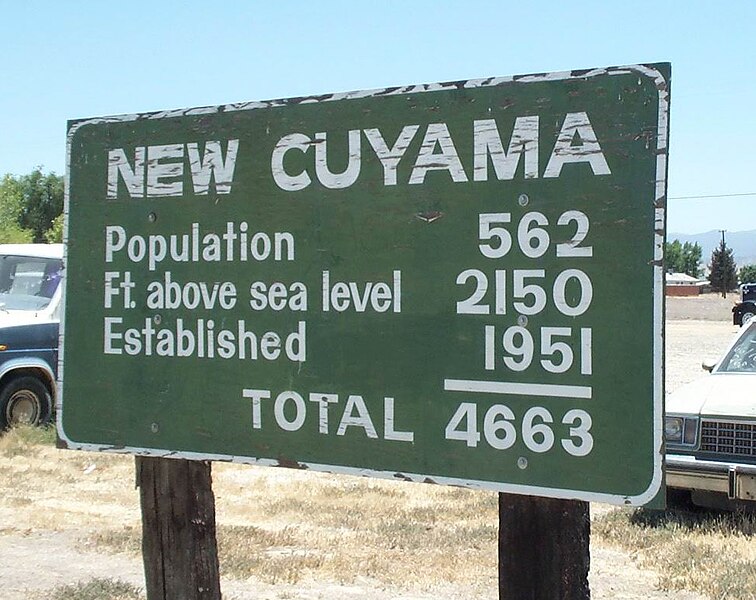

Sign posted on Primero Street in New Cuyama, California: