“Never cry over spilt milk, because it may have been poisoned.” — W.C. Fields

Drinking Problem

I have a 16-ounce bottle of wine and want to make it last as long as possible, so I establish the following plan: On the first day I’ll drink 1 ounce of wine and refill the bottle with water. On the second day I’ll drink 2 ounces of the mixture and refill the bottle with water. On the third day I’ll drink three ounces of the mixture and again refill the bottle with water. If I continue until the bottle is empty, how many ounces of water will I have drunk?

A Muddy Grave

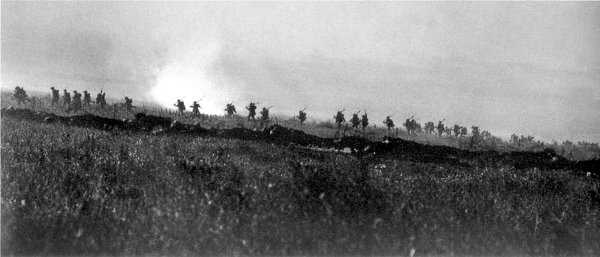

Memories of the first day of the Battle of the Somme, July 1, 1916:

“Before the bombardment started and while everything was peaceful, I could see through my periscope a young Englishman playing his trumpet every evening. We used to wait for this hour but suddenly there was nothing to be heard and we all hoped that nothing had happened to him.” — Feldwebel Karl Stumpf, 169th Regiment

“As the gun-fire died away I saw an infantryman climb onto the parapet into No Man’s Land, beckoning others to follow. As he did so he kicked off a football; a good kick, the ball rose and travelled well towards the German line. That seemed to be the signal to advance.” — Private L.S. Price, 8th Royal Sussex

“For some reason nothing seemed to happen to us at first; we strolled along as though walking in a park. Then, suddenly, we were in the midst of a storm of machine-gun bullets and I saw men beginning to twirl round and fall in all kinds of curious ways as they were hit — quite unlike the way actors do it in films.” — Private W. Slater, 2nd Bradford Pals

“When the English started advancing we were very worried; they looked as though they must overrun our trenches. We were very surprised to see them walking, we had never seen that before. I could see them everywhere; there were hundreds. The officers were in front. I noticed one of them walking calmly, carrying a walking stick. When we started firing, we just had to load and reload. They went down in their hundreds. You didn’t have to aim, we just fired into them. If only they had run, they would have overwhelmed us.” — Musketier Karl Blenk, 169th Regiment

“Imagine stumbling over a ploughed field in a thunderstorm, the incessant roar of the guns and flashes as the shells exploded. Multiply all this and you have some idea of the Hell into which we were heading. To me it seemed a hundred times worse than any storm.” — Private E. Houston, Public Schools Battalion

“The sound was different, not only in magnitude but in quality, from anything known to me. It was not a succession of explosions or a continuous roar; I, at least, never heard either a gun or a bursting shell. It was not a noise, it was a symphony. And it did not move. It hung over us. It seemed as though the air were full of vast and agonised passion, bursting now with groans and sighs, now into shrill screaming and pitiful whimpering, shuddering beneath terrible blows, torn by unearthly whips, vibrating with the solemn pulses of enormous wings. And the supernatural tumult did not pass in this direction or in that. It did not begin, intensify, decline and end. It was poised in the air, a stationary panorama of sound, a condition of the atmosphere, not the creation of man.” — Anonymous NCO, 22nd Manchester Rifles

It would become the bloodiest day in the history of the British Army, with 57,470 casualties. “From that moment all my religion died,” recalled Private C. Bartram of the 94th Trench Mortar Battery. “All my teaching and beliefs in God had left me, never to return.”

Weighty Matters

I’ve accidentally turned the calibration dial on my bathroom scale, so its readings are skewed by a consistent amount. Apart from that it works fine, though. When I stand on the scale it reads 170 pounds, when my wife stands on it it reads 130, and when we stand on it together it reads 292 pounds. How should I adjust the scale?

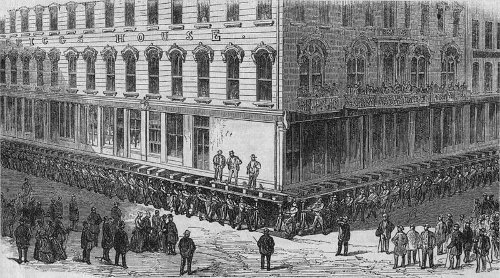

Big Shoulders

Chicago faced a public health crisis in the 1850s as poor drainage led to outbreaks of cholera and typhoid fever. So they raised the town. Large sections of the central city were raised 6 feet on jackscrews while masons installed new foundations beneath them and installed pipes for sewage, water, and gas.

Surprisingly, this went pretty well. “An entire block on Lake street, between Clark and La Salle streets, on the north side of the street, was raised at one time, business in the various stores and offices proceeding as usual,” wrote historian Josiah Seymour Currey. “The facility with which buildings, light and heavy, were raised to the grade established became the talk of the country, and the letters of travelers and correspondents for newspapers abound with reference to the work going on and the odd sensations of going up and down as one passed along the streets.”

One oddity: The streets were raised before the sidewalks, so “until all the sidewalks were raised to grade, people had to go up and down stairs from four to half a dozen steps two or three times in passing a single block,” recalled Chicago Tribune publisher William Bross. “A Buffalo paper got off a note on us to the effect that one of her citizens going along the street was seen to run up and down every pair of cellar stairs he could find. A friend asking after his sanity, was told that the walkist was all right, but that he had been in Chicago a week, and, in traveling our streets, had got so accustomed to going up and down stairs that he got the springhalt and could not help it.”

Quick Thinking

A singular incident occurred in the last run of the Fitzwilliam Hounds, which affords another illustration of the cunning of the fox, and which placed the pack in considerable peril. The ‘find’ took place at Wadworth-wood, and the fox after heading for Rossington Station at a rattling pace, suddenly turned in the direction of Loversall village, where he sought concealment in a bed of rushes near the Carrs. He was, however, speedily compelled to quit his hiding place, and then made again for the railway, where he deliberately lay down on the permanent way and refused to budge. An express train was rapidly approaching, and the pack, being in imminent danger of getting upon the line and being cut to pieces, the huntsman reluctantly and with considerable difficulty drew off the hounds. The fox maintained his position until the express got within a short distance and then quietly made off.

— Times, Dec. 24, 1884

Regeneration

452 = 2025

20 + 25 = 45

453 = 91125

9 + 11 + 25 = 45

454 = 4100625

4 + 10 + 06 + 25 = 45

455 = 184528125

18 + 4 + 5 + 2 + 8 + 1 + 2 + 5 = 45

456 = 8303765625

8 + 3 + 0 + 3 + 7 + 6 + 5 + 6 + 2 + 5 = 45

(Thanks, Dheeraj.)

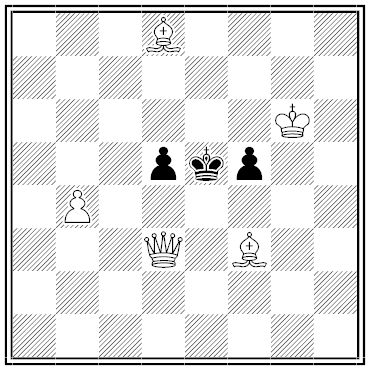

Black and White

From Alexander H. Robbins, A Collection of Chess Problems, 1887. White to mate in two moves.

Opting Out

A fellow at Windsor, who lately ate a cat, has given another proof of the brutality of his disposition — an instance too ferocious and sanguinary, almost, to admit of public representation.

He was at a public-house at Old Windsor, one day in the course of last week, and, without apparent cause, walked out of the house, and with a bill-hook severed his hand from his arm. His brutal courage was strongly marked in this transformation; for the inhuman monster made three strokes with the instrument before he could effect his purpose, and at last actually made a complete amputation. He asigns no other reason for this terrible self-attack than his total disinclination to work, and that this step will compel the overseers of his parish to provide for him during the remainder of his life.

— General Evening Post, Jan. 30, 1790

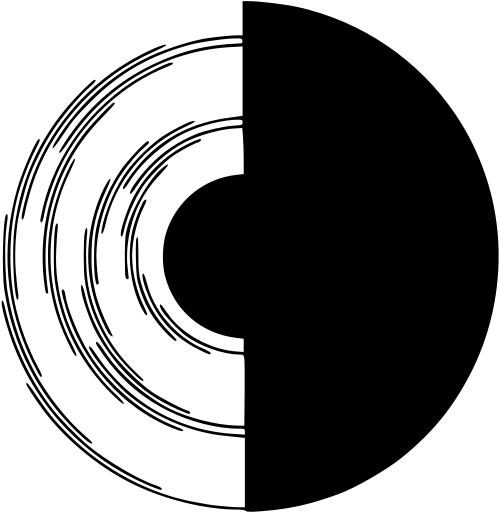

Benham’s Top

Cut out this disc, pierce it with a pencil, and spin it like a top. The colors that appear are not entirely understood; it’s thought that they arise due to the different rates of stimulation of color receptors in the retina. The effect was discovered by the French monk Benedict Prévost in 1826, and then rediscovered 12 times, most famously by the toy maker Charles E. Benham, who marketed an “artificial spectrum top” in 1894. Nature remarked on it that November: “If the direction of rotation is reversed, the order of these tints is also reversed. The cause of these appearances does not appear to have been exactly worked out.”