Prove that the product of four consecutive positive integers cannot be a perfect square.

Ice Route

The largest gem-quality diamond ever found was discovered in a South African mine in 1905. The so-called Cullinan diamond weighed 3,106 carats, or about 1-1/3 pounds.

The Transvaal government purchased the stone and offered it to Edward VII on his 66th birthday, but the problem remained how to transport such a valuable object safely to England. Amid great publicity and heavy security, an ocean liner set out carefully for London.

It was carrying a decoy stone — the real diamond was sent by parcel post. It arrived safely.

(Thanks, Ross.)

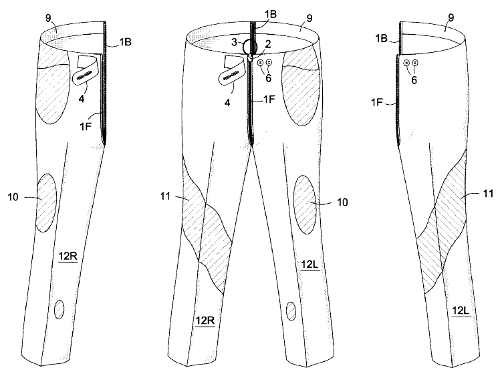

A Leg Up

Allison Andrews had a brainstorm in 1999: If our pants could be easily divided in two, then we could mix and match their halves:

This system saves money by providing a pair of pants that is selectable from the set of all combinations of the left legs against the right legs. Since most members of the combination set do not physically exist at any given time, the user has a large selection set for a fraction of the price.

This way, your wardrobe increases geometrically with each new purchase.

Hell’s Kitchen

Probably you’ll want to skip this one — a recipe “to rost a Goose alive,” from Johann Wecker’s Secrets of Nature, 1582:

Let it be a Duck or Goose, or some such lively Creature, but a Goose is best of all for this purpose, leaving his neck, pull of all the Feather from his body, then make a fire round about him, not too wide, for that will not rost him: within the place set here and there small pots full of water, with Salt and Honey mixed therewith, and let there be dishes set full of rosted Apples, and cut in pieces in the dish, and let the Goose be basted with Butter all over, and Larded to make him better meat, and he may rost the better, put fire to it; do not make too much haste, when he begins to rost, walking about, and striving to flye away, the fire stops him in, and he will fall to drink water to quench his thirst; this will cool his heart and the other parts of his body, and by this medicament he looseneth his belly, and grows empty. And when he rosteth and consumes inwardly, alwayes wet his head and heart with a wet Sponge: but when you see him run madding and stumble, his heart wants moysture, take him away, set him before your Guests, and he will cry as you cut off any part from him, and will be almost eaten up before he be dead, it is very pleasant to behold.

Wecker credits this to a cook named Mizald. William Kitchiner calls it “diabolically cruel”; he quotes another commentator who says “We suppose Mr. Mizald stole this receipt from the kitchen of his Infernal Majesty: probably it might have been one of the dishes the devil ordered when he invited Nero and Caligula to a feast.”

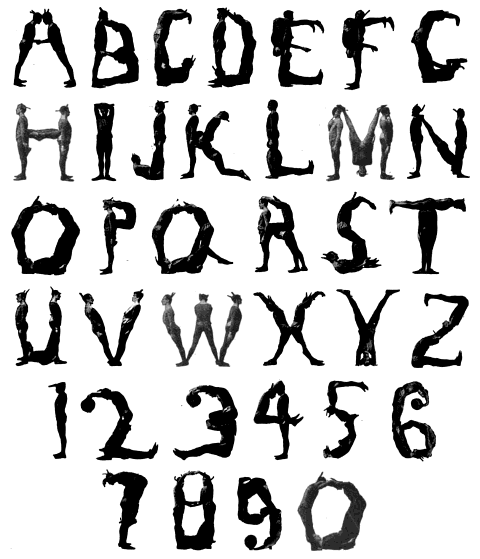

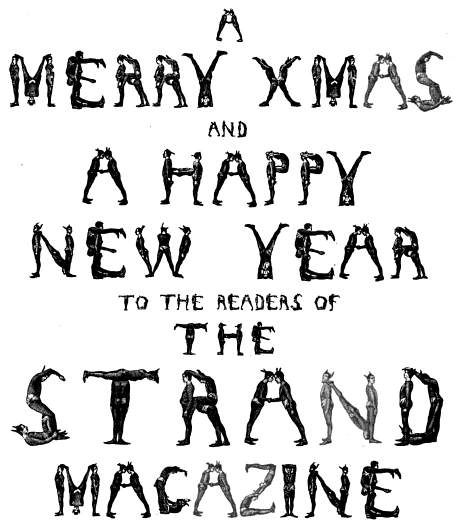

Men of Letters

The Strand set itself a novel challenge in 1897 — to create a complete alphabet using human figures. It engaged an acrobatic trio known as the Three Delevines and set to work in a studio in Plymouth:

“We would venture to say that each and every one of these letters and figures will well repay careful individual study. Each one had first of all to be thought out and designed, then built up in a way which satisfied the author, and finally ‘snapped’ by our artist, for the slightest movement of a head or limb altered the physiognomy of a letter in a surprising way.”

“When the human components had so grouped themselves that the result really looked, even ‘in the flesh,’ like the letter it was supposed to represent, then the author gave the word ‘Go,’ and immediately afterwards, with a sigh of relief, the Three Delevines ‘stood at ease,’ wondering how on earth the next on the list was going to be formed. Neither time nor trouble was spared in the preparation of this most unique of alphabets. Observe that, while we might have inverted the M to form a W, we did not do so; and we think everyone will agree that the last-named letter was well worthy of being designed separately.”

“Perhaps some enterprising publisher would like to publish a whole novel in ‘living’ type. Such a work might, or might not, command a huge sale; but, at least, there can be no two opinions about the human interest of the work.”

Extra Credit

Boeing was demonstrating its new Dash-80 airliner for the nation’s air transport executives in Seattle in August 1955 when test pilot Alvin “Tex” Johnston decided to impress them — instead of a simple flyover he performed a barrel roll:

In 1994, just before test pilot John Cashman undertook the maiden flight of the 777, Boeing president Phil Condit told him, “No rolls.”

Dinner Charge

A curious effect produced by lightning is described to us by Dr. Enfield, writing from Jefferson, Iowa, U.S. A house which he visited was struck by lightning so that much damage was done. After the occurrence, a pile of dinner plates, twelve in number, was found to have every other plate broken. It would seem as if the plates constituted a condenser under the intensely electrified condition of the atmosphere. The particulars are, however, so meagre that it is difficult to decide whether the phenomenon was electrical or merely mechanical.

— Nature, June 12, 1902

Word Ladders

On Christmas Day 1877, assailed by two young ladies with “nothing to do,” Lewis Carroll invented a new “form of verbal torture”: Presented with two words of the same length, the solver must convert one to the other by changing a single letter at a time, with each step producing a valid English word. For example, HEAD can be converted to TAIL in five steps:

HEAD

HEAL

TEAL

TELL

TALL

TAIL

Carroll called the new pastime Doublets and published it in Vanity Fair, which hailed it as “so entirely novel and withal so interesting, that … the Doublets may be expected to become an occupation to the full as amusing as the guessing of the Double Acrostics has already proved.”

In some puzzles the number of steps is specified. In Nabokov’s Pale Fire, the narrator describes a friend who was addicted to “word golf.” “He would interrupt the flow of a prismatic conversation to indulge in this particular pastime, and naturally it would have been boorish of me to refuse playing with him. Some of my records are: HATE-LOVE in three, LASS-MALE in four, and LIVE-DEAD in five (with LEND in the middle).” I’ve been able to solve the first two of these fairly easily, but not the last.

But even without such a constraint, some transformations require a surprising number of steps. Carroll found that 10 were required to turn BLUE into PINK, and in 1968 wordplay expert Dmitri Borgmann declared himself unable to convert ABOVE into BELOW at all.

In a computer study of 5,757 five-letter English words, Donald Knuth found that most could be connected to one another, but 671 could not. One of these, fittingly, was ALOOF. In the wider English language, what proportion of words are “aloof,” words that cannot be connected to any of their fellows? Is ALOOF itself one of these?

In 1917 Sam Loyd and Thomas Edison made this short, which plays with similar ideas. The goat at the end was animated by Willis O’Brien, who would bring King Kong to life 16 years later:

Unquote

“A thing of duty is annoy forever.” — Oliver Herford

A Body at Rest

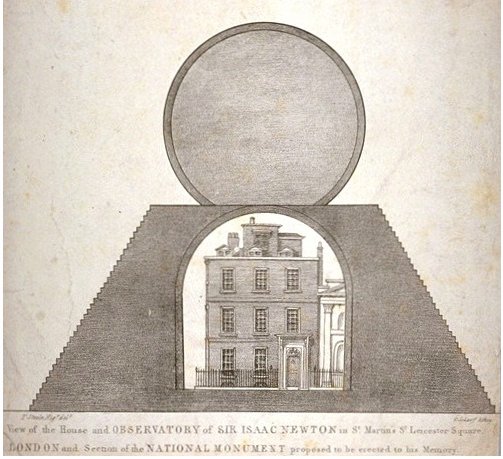

In an anonymous letter to the London Times in 1825, Thomas Steele of Magdalen College, Cambridge, proposed enshrining Isaac Newton’s residence in a stepped stone pyramid surmounted by a vast stone globe. The physicist himself had died more than a century earlier, in 1727, and lay in Westminster Abbey, but Steele felt that preserving his home would produce a monument “not unworthy of the nation and of his memory”:

When travelling through Italy, I was powerfully struck by the unique situation and singular appearance of the Primitive Chapel at Assisi, founded by St. Francis.

As you enter the porch of the great Franciscan church, you view before you this small cottage-like chapel, standing directly under the dome, and perfectly isolated.

Now, Sir, among the many splendid improvements which are making in the capital, would it not be a noble, and perhaps the most appropriate, national monument which could be erected, if an azure hemispherical dome, or what would be better, a portion of a sphere greater than a hemisphere, supported on a massive base, were to be reared, like that of Assisi, over the house and observatory of the writer of the Principia?

The house might be fitted up in such a manner as to contain a council-chamber and library for the Royal Society; and it is perhaps not unworthy of being remarked, that it is not more than about two hundred yards distant from the University Club House.

Protected, by the means which I have described, from the dilapidating influence of rains and winds, the venerable edifice in which Newton studied, or was inspired, — that ‘palace of the soul,’ might stand fast for ages, a British monument more sublime than the Pyramids, though remote antiquity and vastness be combined to create their interest.

Steele wasn’t an architect, and he left the details to others, but he was imagining something enormous: In a subsequent letter to the Mechanics’ Magazine he wrote that “the base of my design [appears] to coincide with the base of St. Paul’s (a sort of crude coincidence of course, in consequence of the angle at the transept), and that the highest point of my designed building should, at the same time, appear to coincide with a point of the great tower of the cathedral, about 200 feet high — the height of the building which I propose to have erected.”

The plan never went forward, but the magazine endorsed the idea: “We need scarcely add, that there is no description of embellishment which might not be with ease introduced into the structure, so as to render it as perpetual a monument to the taste as it would be to the national spirit and gratitude of the British people.”