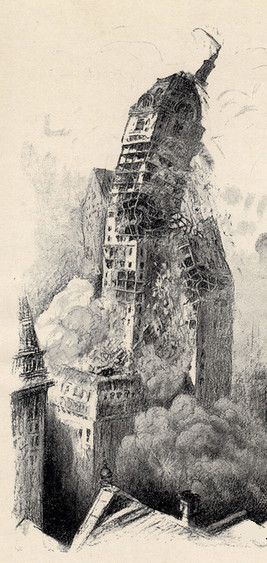

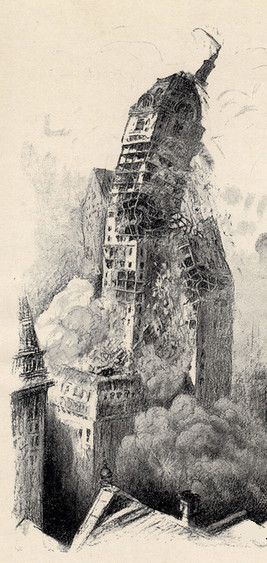

Published in 1915, Cleveland Moffett’s The Conquest of America imagined a German assault on the United States in 1921. Moffett had intended the novel as a warning of the importance of military preparedness, and it was quickly forgotten, but one passage would come to take on an eerie significance — an attack on Manhattan:

‘Ah! So!’ said von Hindenburg, and he glanced at a gun crew who were loading a half-ton projectile into an 11.1-inch siege-gun that stood on the pavement. ‘Which is the Woolworth Building?’ he asked, pointing across the river.

‘The tallest one, Excellency — the one with the Gothic lines and gilded cornices,’ replied one of his officers.

‘Ah, yes, of course. I recognise it from the pictures. It’s beautiful. Gentlemen,’ — he addressed the American officers, — ‘I am offering twenty-dollar gold pieces to this gun crew if they bring down that tower with a single shot. Now, then, careful! …

‘Ready!’

We covered our ears as the shot crashed forth, and a moment later the most costly and graceful tower in the world seemed to stagger on its base. Then, as the thousand-pound shell, striking at the twenty-seventh story, exploded deep inside, clouds of yellow smoke poured out through the crumbling walls, and the huge length of twenty-four stories above the jagged wound swayed slowly toward the east, and fell as one piece, flinging its thousands of tons of stone and steel straight across the width of Broadway, and down upon the grimy old Post Office Building opposite.

‘Sehr gut!’ nodded von Hindenburg. ‘It’s amusing to see them fall. Suppose we try another? What’s that one on the left?’

‘The Singer Building, Excellency,’ answered the officer.

‘Good! Are you ready?’

Then the tragedy was repeated, and six hundred more were added to the death toll, as the great tower crumbled to earth.

‘Now, gentlemen,’ — von Hindenburg turned again to the American officers with a tiger gleam in his eyes, — ‘you see what we have done with two shots to two of your tallest and finest buildings. At this time to-morrow, with God’s help, we shall have a dozen guns along this bank of the river, ready for whatever may be necessary.’

In the end J.P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, and John D. Rockefeller are held hostage and ordered to raise a billion dollars to indemnify the city. “The Conquest of America is as full of thrills as the most excitable and fearful patriot need ask,” raved the Independent. “If all the prominent Americans named in the tale, as hostages or otherwise, get about the business of preparedness, this invasion will never be.”