oblectation

n. delight, pleasure, enjoyment

adlubescence

n. pleasure or delight

deliciate

v. to delight oneself

oblectation

n. delight, pleasure, enjoyment

adlubescence

n. pleasure or delight

deliciate

v. to delight oneself

On Aug. 17, 1957, in a game against the New York Giants, Philadelphia Phillies center fielder Richie Ashburn hit a foul ball into the stands and hit Alice Roth, the wife of Philadelphia Bulletin sports editor Earl Roth.

The game was stopped, and Roth received emergency medical treatment for a broken nose.

As she was being carried out on a stretcher, Ashburn hit a second foul — and hit her again.

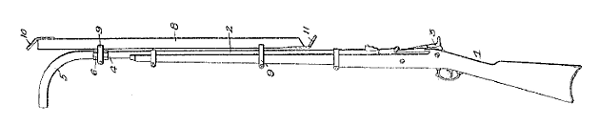

Philadelphia inventor Jones Wister conceived a curious weapon in 1916:

One object of the invention is to so construct a fire arm that it can be used in a trench with the aid of a periscope without exposing the soldier to the fire of the enemy. This object I attain by curving the outer end of the barrel so as to deflect the projectile in a direction at an angle to the longitudinal line of the fire arm.

Germany experimented with a similar design during World War II and found that the barrel gave out very quickly under the enormous stress; the bullets sometimes shattered. Wister had envisioned that the same principle might be used with machine guns and even cannon — let’s hope he didn’t try that out.

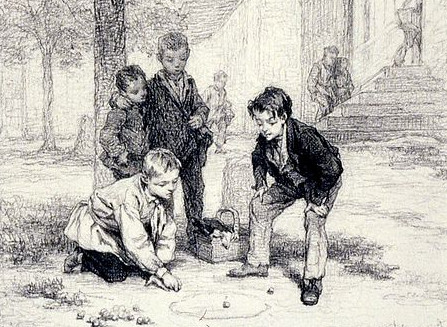

Alan and Bob are playing a game of marbles. Alan has two marbles, Bob has one, and each rolls to try to come nearest to a fixed point. If the two have equal skill, what is the chance that Alan will win?

There seem to be two contradictory arguments. On the one hand, each of the three marbles has an equal chance of winning, and two of them belong to Alan, so it seems that there’s a 2/3 chance that Alan will win.

On the other hand, there are four possible outcomes: (a) both of Alan’s rolls are better than Bob’s, (b) Alan’s first roll is better than Bob’s, but his second is worse, (c) Alan’s first roll is worse than Bob’s, but his second is better, and (d) both of Alan’s rolls are worse than Bob’s. In 3 of the 4 cases, Alan wins, so it appears that his overall chance of winning is 3/4.

Which argument is correct?

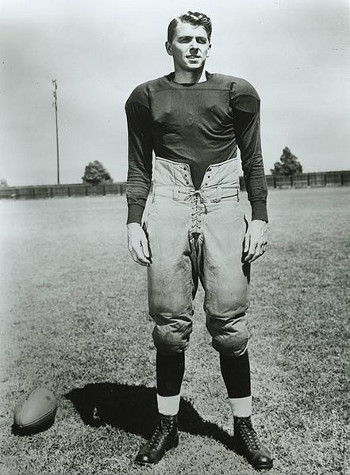

In 1940 Ronald Reagan was voted a “Twentieth Century Adonis” by the University of Southern California’s Division of Fine Arts for having the “most nearly perfect male figure.”

He posed for student sculptors there.

Twenty-nine-year-old James Landis was operating a currency-wrapping machine at the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing when an idea occurred to him. He went home and cut ordinary bond paper into pieces the size of U.S. currency, and wrapped them to resemble the bricks of $20 bills that he produced at work. On Dec. 30, 1953, he smuggled these packages into work with him and hid them in a locker room. Then he wrapped two bundles of real $20 bills in kraft paper and carried them to a storage area. There he unwrapped them, saving the labels, put the bills into two paper bags he had brought from home, and hid these.

He worked the rest of the morning at his station, then returned to the dummy bundles he had brought from home. In a toilet stall he affixed the labels to the ends of the dummy bricks, using glue he had brought from his station, and he rubber-stamped each “HA 12-31-53,” indicating that a bureau employee with the initials H.A. had wrapped the packages on Dec. 31, 1953. Then he carried the dummy bricks to a storage skid on the first floor, where he left them among packages of genuine $20 bills.

At 3:10 p.m. he finished work, changed clothes, and retrieved one of the paper bags from the dead storage area, using a pair of dirty trousers to conceal the $128,000 that the bag held. And he walked out of the building.

Landis and three friends set about buying inexpensive merchandise in order to shed the stolen money and get change, but it wasn’t to last long. When he returned to work on Jan. 4, a stockman picked up two bricks of currency and noted that one of them felt light. When the dummy bricks were discovered, the Secret Service began an investigation; Landis drove to Virginia and tried to hide the money with his father-in-law, who turned him in the following morning. Landis and his friends pleaded guilty on May 3, and all were sent to prison.

Ixonia, Wisconsin, was named at random.

Unable to agree on a name for the town, the residents printed the alphabet on slips of paper, and a girl named Mary Piper drew letters successively until a name was formed.

The town was christened Ixonia on Jan. 21, 1846, and it remains the only Ixonia in the United States.

A riddle attributed to British prime minister George Canning, among many others:

A word there is of plural number,

Foe to ease and tranquil slumber.

Any other word you take

And add an S will plural make;

But if you add an S to this,

So strange the metamorphosis,

Plural is plural now no more

And sweet what bitter was before.

Astronaut John Young smuggled a corned beef sandwich into space. As Gemini 3 was circling Earth in March 1965, Young pulled the sandwich out of his pocket and offered it to Gus Grissom:

Grissom: What is it?

Young: Corned beef sandwich.

Grissom: Where did that come from?

Young: I brought it with me. Let’s see how it tastes. Smells, doesn’t it?

Grissom: Yes, it’s breaking up. I’m going to stick it in my pocket.

Young: Is it? It was a thought, anyway.

“Wally Schirra had the sandwich made up at a restaurant at Cocoa Beach a couple of days before, and I hid it in a pocket of my space suit,” Young explained later. “Gus had been bored by the official menus we’d practiced with in training, and it seemed like a fun idea at the time.”

Grissom wrote, “After the flight our superiors at NASA let us know in no uncertain terms that non-man-rated corned beef sandwiches were out for future space missions. But John’s deadpan offer of this strictly non-regulation goodie remains one of the highlights of our flight for me.”

“The greatest masterpiece in literature is only a dictionary out of order.” — Jean Cocteau