“Fashion is something barbarous, for it produces innovation without reason and imitation without benefit.” — George Santayana

The Shoe Fits

William F. Buckley Jr. called Norman Mailer an egotist, “almost unique in his search for notoriety and absolutely unequalled in his co-existence with it.”

Mailer called Buckley a “second-rate intellect incapable of entertaining two serious thoughts in a row.”

In 1966 Buckley sent Mailer an autographed copy of The Unmaking of a Mayor, the memoir of his unsuccessful run for mayor of New York City the previous year.

Mailer turned to the index and looked up his own name. There he found, in Buckley’s handwriting, the words “Hi, Norman.”

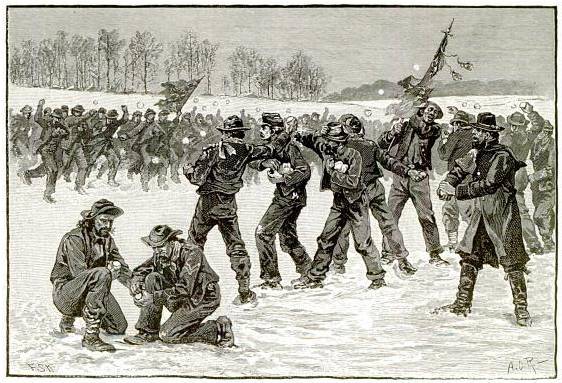

Cold War

The least sanguinary battle of the Civil War was a snowball fight among Confederate troops near Port Royal, Va., on Feb. 25, 1863. A participant described the melee in the Savannah Daily Morning News:

We finally got our column in line and advanced with a shout — but a new mistake precipitated the catastrophe. The ‘Tar-heels’ had provided themselves with haversacks filled to the brim with ammunition — whereas we only had a ball or two in our possession. When these were exhausted, of course, we had to improvise for the occasion, while our foes could pelt us mercilessly with an unremitting hail and thus interfere materially with the process of manufacturing ours. Under these circumstances our plan of attack should have been to charge furiously to a distance of five paces of the Van Winkle, fire one volley and then charge again, making the contest a hand to hand one. Had we done so, I have no doubt we would have swept the encampment. But on the contrary we charged up very near and then halted and commenced to fire. The consequence was that our ammunition was soon exhausted, while that of the Rips was only lightened enough to expedite their movements.

“Thus ended one of the most memorable combats of the war,” he concluded. “A part of it was witnessed by Gen. Jackson and his staff. I wish the old faded uniforms could have participated in it. I want to throw one snow-ball at Stonewall Jackson.”

Methodical

In April 1922, 17-year-old Ernest Albert Walker, the footman to an English colonel, approached a policeman in Tonbridge and said, “I believe I have done a murder.” At the house, investigators discovered the body of messenger Raymond Charles Davis and a handwritten agenda on black-edged notepaper:

- Ring up Sloane Street messenger office for boy.

- Wait at front door.

- Invite him in.

- Bring him downstairs.

- Ask him to sit down.

- Hit him on the head.

- Put him in the safe.

- Keep him tied up.

- At 10.30 torture.

- Prepare for end.

- Sit down, turn gas on.

- Put gas light out.

- Sit down, shut window.

Walker had also left a note for the butler:

I expect you will be surprised to see what I have done. Well since my mother died I have made up my mind to die also. You know you said a gun-case had been moved and I denied it. Well, it had, I got a gun out and loaded it and made a sling for my foot to pull the trigger, but my nerve went and I put it away. I rang up the Sloane Square office for a messenger boy and he came to the front door. I asked him to come in and wait, and I brought him to the pantry and hit him on the head with a coal-hammer. So simple! Then I tied him up and killed him. I killed him, not the gas. Then I sat down and turned the gas full on. I am as sane as ever I was, only I cannot live without my dear mother. I didn’t half give it to that damned boy. I made him squeak. Give my love to Dad and all my friends.

“I don’t know what made me do it,” he told police. “I came to Tonbridge as it would give me plenty of time to think and tell the police here.” He was judged “guilty but insane” and committed to the Broadmoor psychiatric hospital.

Light-Hearted

Fred Astaire composed a unique dance solo for 1951’s Royal Wedding — he celebrates his love for Sarah Churchill by dancing on the walls and ceiling of his hotel room.

The effect was produced by situating the entire room in a steel-reinforced cylindrical chamber 20 feet in diameter, which the crew could turn as Astaire danced. Cameraman Robert Planck was strapped to a board that rotated with the set, producing the illusion that the room was stationary and that the dancer was freed from gravity.

The details required further trickery. “Fred’s coat was sewed to the chair, and the chair was screwed to the floor,” remembered director Stanley Donen. The photograph that Astaire admires is fitted with magnets. “The draperies were made of wood. There’s nothing soft in the shot. There was only one cut during the sequence — while he is at midpoint on the wall, necessitated by having to change the roll of film. We rehearsed this [scene] for weeks and filmed it in one morning. … We were literally through with the entire sequence by lunch.”

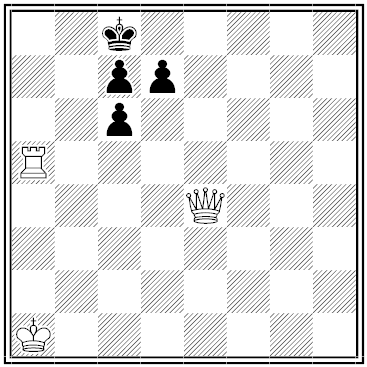

Black and White

Credentials

When Steven Spielberg dropped out of college in 1968, he was only a few credits short of a diploma.

So in 2002, after winning three Oscars, five honorary doctorates, and two lifetime achievement awards, he returned to California State University, Long Beach, to complete a degree in film and electronic arts.

He placed out of FEA 309, the advanced filmmaking class. To demonstrate his proficiency, he submitted Schindler’s List.

Always Home

The largest privately owned residential yacht on earth is The World, a private floating community conceived in 1997 by Norwegian shipping magnate Knut Kloster. The ship is owned jointly by its residents, 130 families from 19 countries, who spend an average of four months on board each year, and it circumnavigates the globe continuously on an itinerary that they choose.

Since its launch in 2002, the ship has visited 800 ports in 140 countries. It has 165 bespoke apartments, including a six-bedroom penthouse suite, a 7,000-square-foot spa, four major restaurants, three cafes, six bars, two swimming pools, a full-size tennis court, a driving range, an art gallery, a night club, a 12,000-bottle wine cellar, and a theater. The average resident is 64, and 35 percent are under 50.

The original inventory of units sold out in 2006, but “there are a select number of Residences available for resale.”

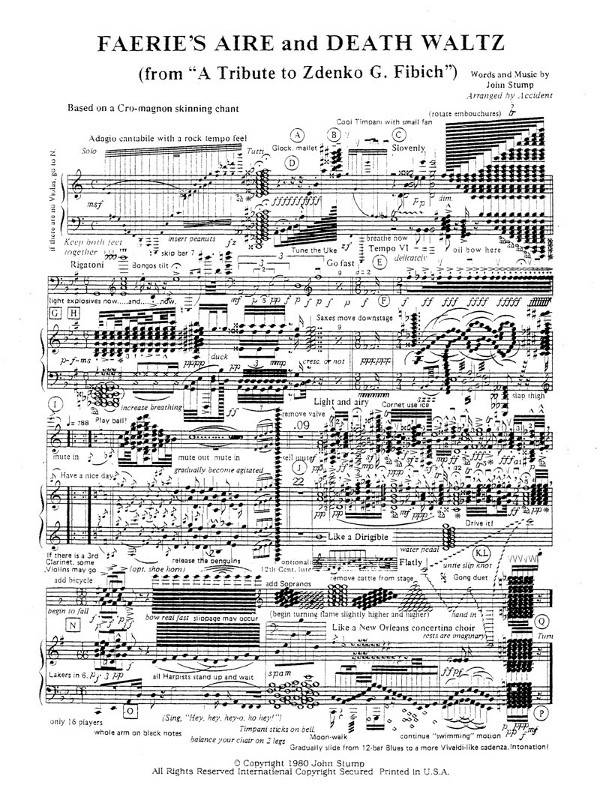

Difficult Music

Faerie’s Aire and Death Waltz, by composer John Stump, includes the directions “Add bicycle,” “Duck,” and “Cool timpani with small fan.” The piece fills a single page.

To perform Stockhausen’s Helikopter-Streichquartett you’ll need four helicopters and a string quartet. A moderator introduces the musicians, each of whom boards a helicopter, and the four perform the piece while circling the auditorium at a distance of 6 kilometers. The audience watches and listens via audio and video monitors. At the end, the helicopters land and the musicians re-enter the hall to the sound of slowing rotor blades.

Marc-André Hamelin composed Circus Galop for player piano — it’s impossible for a human to play, as up to 21 notes are struck simultaneously.

Reversible Rhyme

Word Ways reader Art Benjamin found this limerick on a blackboard at Carnegie Mellon in the 1980s:

First let me say that I’m cursed.

I’m a poet who gets time reversed.

Reversed time,

Gets who poet a I’m,

Cursed I’m that say me let first.

No author was given.