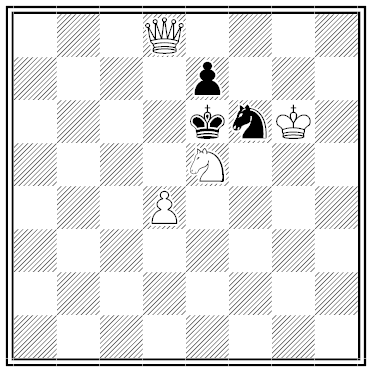

By H. Van Beek, Chemnitzer Wochenschach, 1926 (special prize). White to mate in two moves.

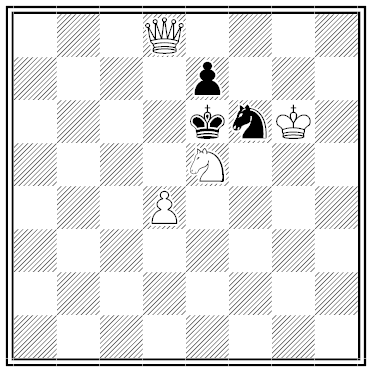

By H. Van Beek, Chemnitzer Wochenschach, 1926 (special prize). White to mate in two moves.

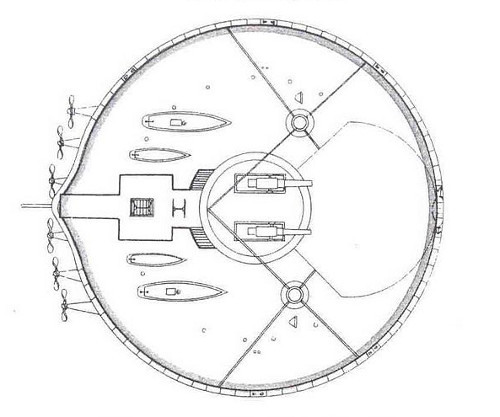

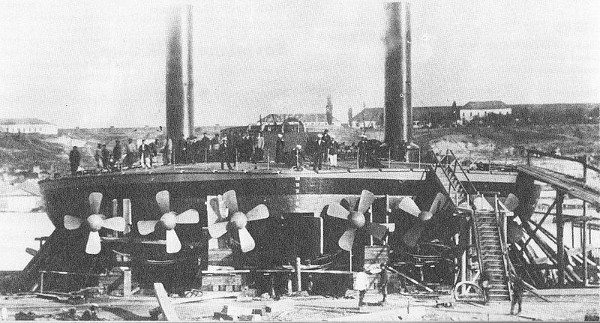

The Russian navy undertook an odd experiment in 1871: circular warships. With their broad, flat bottoms, the Novgorod (above) and the Vice Admiral Popov (below) were intended to bear heavy guns into shallow coastal waters where more conventional warships could not go. But without keels they were slow and difficult to maneuver, and in cross currents they tended to spin. They served briefly in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78 but were relegated as storeships in 1903 and scrapped nine years later.

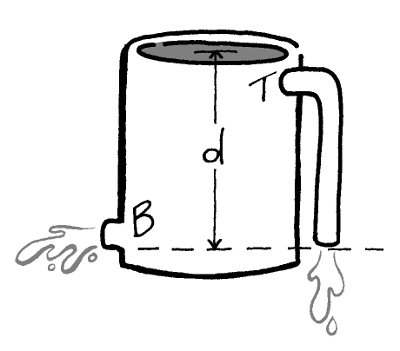

A tank of water has two holes of equal area, one at top and one at bottom. The top one leads to a downspout, so that both holes discharge their water at the same level. Ignoring friction, which hole produces the faster flow of water?

You actually don’t need to know the physics in order to solve this — it yields to an insight.

accubation

n. the act or posture of reclining on a couch

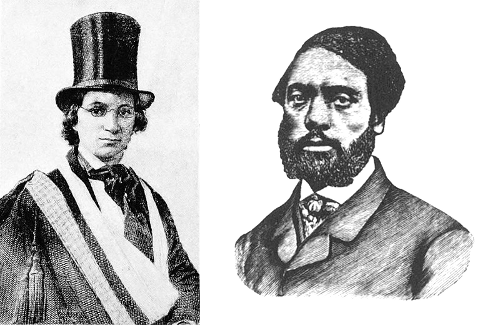

In 1848, Ellen and William Craft resolved to flee slavery, but they needed a way to get from Macon, Ga., to the free states in the north. William could never travel such a distance alone, but Ellen’s skin was fair enough that she could pass for white. So she disguised herself as a white male cotton planter attended by William, her slave. (She had to pose as a man because a white woman would not have traveled alone with a male slave.) The two asked leave to be away for the holidays, the illiterate Ellen bound her arm in a sling to escape being asked to write, and they departed on Dec. 21. Over the next four days:

On Dec. 25, after a journey of more than 800 miles, they arrived in Philadelphia:

On leaving the station, my master — or rather my wife, as I may now say — who had from the commencement of the journey borne up in a manner that much surprised us both, grasped me by the hand, and said, ‘Thank God, William, we are safe!’ then burst into tears, leant upon me, and wept like a child. The reaction was fearful. So when we reached the house, she was in reality so weak and faint that she could scarcely stand alone. However, I got her into the apartments that were pointed out, and there we knelt down, on this Sabbath, and Christmas-day, — a day that will ever be memorable to us, — and poured out our heartfelt gratitude to God, for his goodness in enabling us to overcome so many perilous difficulties, in escaping out of the jaws of the wicked.

The Crafts went on a speaking tour of New England to share their story with abolitionists, then moved to England to evade recapture under the Fugitive Slave Act. They returned only in 1868, when they established a school in Georgia for newly freed slaves.

Whenas in silks my Julia goes

Then, then (methinks) how sweetly flows

That liquefaction of her clothes.

Next, when I cast mine eyes and see

That brave vibration each way free;

Oh how that glittering taketh me!

— Robert Herrick, 1648

Whenas galoshed my Julia goes,

Unbuckled all from top to toes,

How swift the poem becometh prose!

And when I cast mine eyes and see

Those arctics flopping each way free,

Oh, how that flopping floppeth me!

— Bert Leston Taylor, 1922

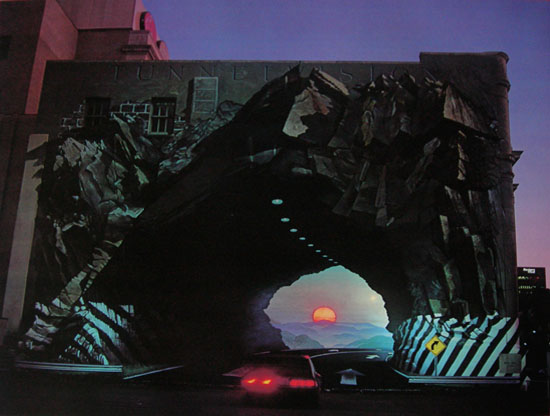

American muralist Blue Sky (formerly Warren Edward Johnson) painted Tunnelvision on the wall of the Federal Land Bank in Columbia, S.C., in 1975. “The idea for ‘Tunnelvision’ came in a dream. I woke up early in the morning and just sketched it out. I’d already seen the wall, I’d sat and studied it for hours, just waiting to see what would come before my eyes, and nothing came. And early one morning, I woke up and it was there. … That’s why I call it ‘Tunnelvision.’ Because it was a vision in a dream.” Wikipedia adds, “Rumors abound that several drunk drivers have attempted to drive into the tunnel.”

Passing trains clear a three-kilometer “tunnel of love” through the forest near Klevan, Ukraine, each spring. The trains serve a local fiberboard factory.

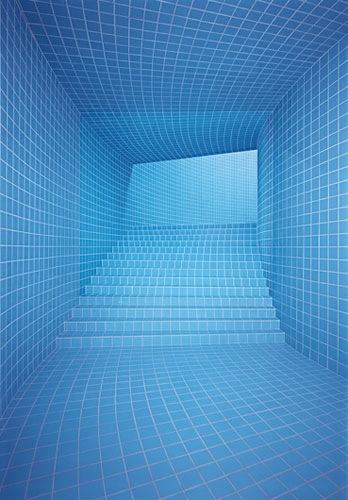

Visitors to the modern art exhibition documenta 6 in Kassel, Germany, in 1977 encountered a blue-tiled tunnel that led to the promise of daylight. They walked 14 meters into the tunnel and climbed four steps before discovering that the rest was an image painted skillfully on canvas by artist Hans Peter Reuter. “The secret of this perfect illusion lies in the combination of a realistic space with a painted surface,” writes Eckhard Hollmann and Jürgen Tesch in A Trick of the Eye (2004). “The picture alone on a white wall could never hope to have the same effect.”

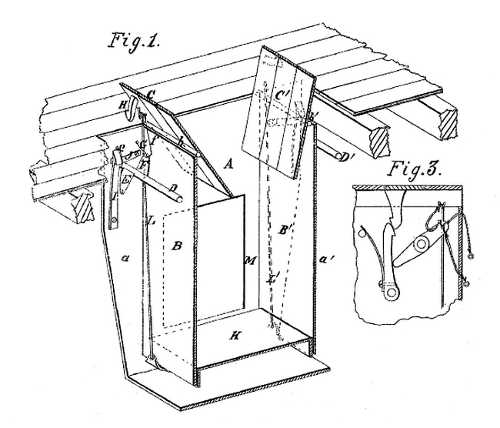

William Carr’s “improved burglar-trap,” patented in 1868, is a man-size version of a no-kill mousetrap. The unwitting burglar steps on the trapdoor and falls into the chamber, where his own weight on the false bottom pulls the doors shut again.

“It will be seen that the catches II II’ and I I act, in connection with the weight of the person upon the platform, in retaining the doors in their closed condition, and, even in case the prisoner should succeed in scaling the walls of the chamber, the locking-devices H H’ and I I’ will effectually prevent him forcing open the trap-doors.”

During the day the proprietor can pull a cord to engage the catches by hand, to prevent his customers from falling in themselves.

I never deliberately sat down and ‘created’ a character in my life. I begin to write incidents out of real life. One of the persons I write about begins to talk this way and one another, and pretty soon I find that these creatures of the imagination have developed into characters, and have for me a distinct personality. These are not ‘made,’ they just grow naturally out of the subject. That was the way Tom Sawyer, Huck Finn and other characters came to exist. I couldn’t to save my life deliberately sit down and plan out a character according to diagram. In fact, every book I ever wrote just wrote itself. I am really too lazy to sit down and plan and fret to ‘create’ a ‘character.’ If anybody wants any character ‘creating,’ he will have to go somewhere else for it. I’m not in the market for that. It’s too much like industry.

— “Mark Twain Tells the Secrets of Novelists,” New York American, May 26, 1907

Cartoonist Mark Heath has agreed to let me republish some of his wonderful work here. Let me know what you think.