“Great good nature, without prudence, is a great misfortune.” — Benjamin Franklin

Limericks

A globe-trotting man from St. Paul

Made a trip to Japan in the faul.

One thing he found out,

As he rambled about,

Was that Japanese ladies St. Taul.

A censor, whose name was Magee,

Suppressed the whole dictionaree;

When the public said, “No!”

He replied, “It must go!

It has alcohol in it, you see!”

There was a young man from the city,

Who met what he thought was a kitty;

He gave it a pat

And said, “Nice little cat!”

And they buried his clothes out of pity.

— Carolyn Wells’ Book of American Limericks, 1925

Order and Chaos

Arrange a deck of cards in alternating colors, black and red. Now cut the deck so that the bottom card of one pile is black and the other is red. Riffle-shuffle the two piles together again. Now remove cards from the top of the pack in pairs. How many of these pairs should we expect to contain cards of differing colors?

Surprisingly, all of them will. During the shuffle, suppose a black card falls first. It must be followed by either the next card in its own pile, which is red, or the first card from the other pile, which is also red. Either way, this first pair will contain one black card and one red card, and by the same principle so will each of the other 25 pairs produced by the shuffle. This effect was first identified by mathematician Norman Gilbreath in 1958.

Related: Arrange the deck in a repeating cycle of suits, such as spade-heart-club-diamond, spade-heart-club-diamond, etc. Ranks don’t matter. Now deal about half of this deck onto the table and riffle-shuffle the two halves back together. If you draw cards from the top in groups of four, you’ll find that each quartet contains one card of each suit.

See So Much for Entropy.

Cast Away

In July 1761 an illegal slave ship foundered near Tromelin, a speck of land 200 miles east of Madagascar. After six months on the island, the surviving gentlemen and sailors assembled a makeshift boat and departed, promising to return for the 60 slaves left on the island. They never did.

The slaves kept a fire going for 15 years while they struggled to survive on an island of barely 0.3 square miles. They fashioned houses from coral and sand, built a communal oven, and subsisted on turtles and seabirds.

“We have found evidence of where they lived and what they ate,” archaeologist Max Guérout told the Independent in 2007. “We have found copper cooking utensils, repaired, over and over again, which must originally have come from the wreck of the ship.”

Many of the castaways simply succumbed. At one point 18 left on a makeshift raft; it’s not known whether they reached land. In 1776 a French sailor was shipwrecked on the island, built a raft, and escaped to Mauritius with three men and three women. When a rescue ship arrived for the last seven castaways, they included a grandmother, her daughter, and an 8-month-old grandchild who had been born on the island.

The governor in Ile de France declared them free, since they had been bought illegally. He adopted the family of three and named the boy Jacques Moise. His surname is a French form of Moses — a baby rescued from water.

In a Word

scrannel

adj. unmelodious

Heat and Light

If an opinion contrary to your own makes you angry, that is a sign that you are subconsciously aware of having no good reason for thinking as you do. If some one maintains that two and two are five, or that Iceland is on the equator, you feel pity rather than anger, unless you know so little of arithmetic or geography that his opinion shakes your own contrary conviction. The most savage controversies are those about matters as to which there is no good evidence either way. Persecution is used in theology, not in arithmetic, because in arithmetic there is knowledge, but in theology there is only opinion. So whenever you find yourself getting angry about a difference of opinion, be on your guard; you will probably find, on examination, that your belief is going beyond what the evidence warrants.

— Bertrand Russell, “An Outline of Intellectual Rubbish,” 1943

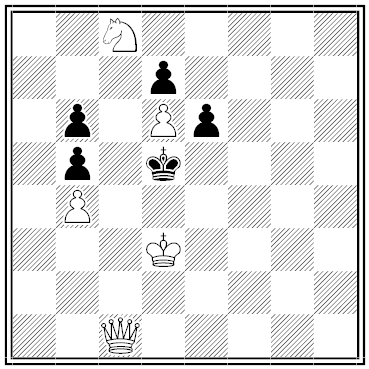

Black and White

A Few Words

At the climax of the 1934 film The Black Cat, Boris Karloff recites a “black mass” over a swooning Jacqueline Wells:

Cum grano salis. Fortis cadere cedere non potest. Humanum est errare. Lupis pilum mutat, non mentem. Magna est veritas et praevalebit. Acta exteriora indicant interiora secreta. Aequam memento rebus in arduis servare mentem. Amissum quod nescitur non amittitur. Brutum fulmen. Cum grano salis. Fortis cadere cedere non potest. Fructu, non foliis arborem aestima. Insanus omnes furere credit ceteros. Quem paenitet peccasse paene est innocens.

This sounds marvelous in Karloff’s portentous baritone, but it’s weaker in translation:

With a grain of salt. A brave man may fall, but he cannot yield. To err is human. The wolf may change his skin, but not his nature. Truth is mighty, and will prevail. External actions show internal secrets. Remember when life’s path is steep to keep your mind even. The loss that is not known is no loss at all. Heavy thunder. With a grain of salt. A brave man may fall, but he cannot yield. By fruit, not by leaves, judge a tree. Every madman thinks everybody mad. Who repents from sinning is almost innocent.

He might have added Omnia dicta fortiora si dicta Latina: “Everything sounds more impressive in Latin.”

The Knee on Its Own

A lone knee wanders through the world,

A knee and nothing more;

It’s not a tent, it’s not a tree,

A knee and nothing more.

In battle once there was a man

Shot foully through and through;

The knee alone remained unhurt

As saints are said to do.

Since then it’s wandered through the world,

A knee and nothing more.

It’s not a tent, it’s not a tree,

A knee and nothing more.

— Christian Morgenstern, 1905

Yankee Panky

The New York Yankees saw an unusual trade in 1972: Pitchers Mike Kekich and Fritz Peterson traded families. Kekich traded his wife, Susan, two children, and a Bedlington terrier for Marilyn Peterson, the two Peterson children, and a poodle. “We didn’t trade wives, we traded lives,” Kekich said.

“They were really close, and their families were close,” remembered Yankees catcher Jake Gibbs, who had played with both men. “I guess we just didn’t know how close. Of course, they were both left-handers. You can never tell about lefties.”

The storm of attention that accompanied the trade began to erode the players’ friendship — Yankees executive Dan Topping quipped, “We may have to call off Family Day this season” — and Kekich was traded to the Indians later that year.

Marilyn Peterson and Mike Kekich eventually ended their relationship, but Fritz Peterson married Susanne Kekich in 1974 and raised four children with her.

The two friends were never close again. “All four of us had agreed in the beginning that if anyone wasn’t happy, the thing would be called off,” Kekich said. “But when Marilyn and I decided to call it off, the other couple already had gone off with each other.”