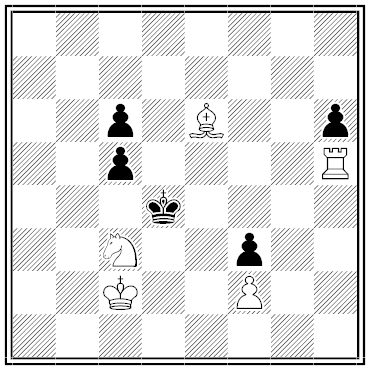

By A.B. Arnold, from the 1859 problem tournament of the New York Clipper. White to mate in two moves.

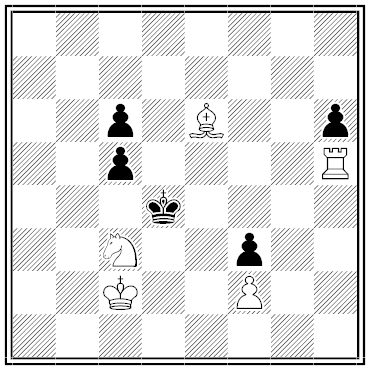

By A.B. Arnold, from the 1859 problem tournament of the New York Clipper. White to mate in two moves.

Yesterday too little nevertheless

Thereupon notwithstanding everywhere

At that point next together the way that

Such as at length thus at the time as much as

Formerly less thither of yore

Here always in enough already near

Quite so sometimes almost a lot all right

Evermore such still within hard never

When hither wrongly once again

Forthwith gladly late in the day henceforth

Maybe drop by drop indeed all the way

Why face to face fast to be sure quasi

Immediately unhesitatingly

Thoughtlessly frontwards backwards squattingly

Non-stop post-haste suddenly from now on

In succession torrentially finally

Incessantly tomorrow emulously

Whereas along in turn now over there

Elsewhere today of course so there pell-mell

Outside there all of a sudden round about

No way in brief no better than so-so

Worse rather than better out worse and worse.

— Noël Arnaud

Take an ordinary magic square and replace its numbers with resistors of the same ohmic value. Now the set of resistors in each row, column, and diagonal will yield the same total resistance value when joined together end to end.

This paramagic square, by Lee Sallows, is similar — except that the resistors must be joined in parallel:

In 1982, 74-year-old David Martin found the skeleton of a carrier pigeon in the chimney of his house in Bletchingley, Surrey. Attached to its leg was an encrypted message believed to have been sent from France on D-Day, June 6, 1944:

AOAKN HVPKD FNFJW YIDDC

RQXSR DJHFP GOVFN MIAPX

PABUZ WYYNP CMPNW HJRZH

NLXKG MEMKK ONOIB AKEEQ

WAOTA RBQRH DJOFM TPZEH

LKXGH RGGHT JRZCQ FNKTQ

KLDTS FQIRW AOAKN 27 1525/6

What does it mean? No one knows — the message still hasn’t been deciphered.

“Although it is disappointing that we cannot yet read the message brought back by a brave carrier pigeon,” announced Britain’s Government Communications Headquarters last November, “it is a tribute to the skills of the wartime code makers that, despite working under severe pressure, they devised a code that was undecipherable both then and now.”

UPDATE: Gord Young of Peterborough, Ontario, claimed to have cracked the code last month using a World War I code book that he had inherited from his great-uncle. He believes the report was written by 27-year-old Lancashire Fusilier William Stott, who had been dropped into Normandy to report on German positions. Stott was killed a few weeks after the report. Here’s Young’s solution:

AOAKN – Artillery Observer At “K” Sector, Normandy

HVPKD – Have Panzers Know Directions

FNFJW – Final Note [confirming] Found Jerry’s Whereabouts

DJHFP – Determined Jerry’s Headquarters Front Posts

CMPNW – Counter Measures [against] Panzers Not Working

PABLIZ – Panzer Attack – Blitz

KLDTS – Know [where] Local Dispatch Station

27 / 1526 / 6 – June 27th, 1526 hours

Young says that the portions that remain undeciphered may have been inserted deliberately in order to confuse Germans who intercepted the message. “We stand by our statement of 22 November 2012 that without access to the relevant codebooks and details of any additional encryption used, the message will remain impossible to decrypt,” a GCHQ spokesman told the BBC on Dec. 16. But he said they would be happy to look at Young’s proposed solution.

(Thanks, John and Ivan.)

A family has two children, and you know that at least one of them is a boy. What is the probability that both are boys? There are four possibilities altogether (boy-boy, boy-girl, girl-boy, and girl-girl), and we can eliminate the last, so it would seem that the answer is 1/3.

But now suppose you visit a family that you know has two children, and that a boy comes into the room. What is the probability that both children are boys? Of the two children, you know that this one is a boy, and there is a probability of 1/2 that the other is a boy. So it seems that there is a probability of 1/2 that both are boys.

How can this be? We seem to have the same amount of information in both cases. Why does it lead us to two different conclusions?

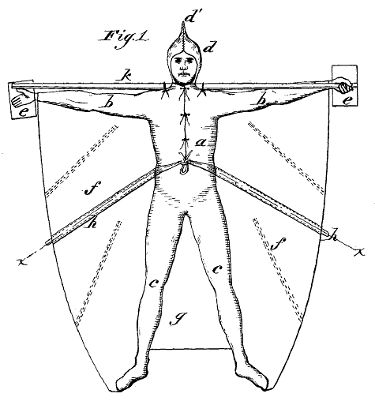

Montana inventor William Beeson offered the swimming apparatus above in 1881 — a suit fitted with a membrane that “acts like wings or fins, which, from the movement of the legs and arms effect a propulsion through the water.”

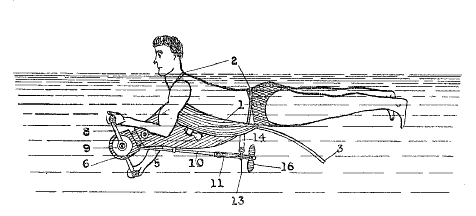

In 1910 O.B. Lyons patented the “life preserver and swimming machine” below — just turn the handle to drive the propeller.

Presumably you could combine the two to go twice as fast.

Another puzzle by Lewis Carroll:

In a group of soldiers, if 70 percent have lost an eye, 75 percent an ear, 80 percent an arm, 85 percent a leg, what percentage, at least, must have lost all four?

“A machine is a great moral educator. If a horse or a donkey won’t go, men lose their tempers and beat it; if a machine won’t go, there is no use beating it. You have to think and try till you find what is wrong. That is real education.” — Gilbert Murray

When Charles Dickens died in 1870, he was midway through composing a novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood. The book was published without a conclusion; Dickens had completed 22 chapters and a general outline, but he nowhere identified the murderer.

This unfortunate state of affairs persisted until 1873, when a Vermont printer named Thomas James announced that Dickens had contacted him during a Brattleboro séance and asked his help in completing the novel. James and the ghost collaborated for weeks, with James slipping into a nightly trance and scribbling down the author’s dictation; when James flagged, Dickens would send notes of encouragement and explain that others in the afterworld were following the project with interest.

The completed novel, attributed to “the Spirit-Pen of Charles Dickens, through a Medium,” became a bestseller in America but was largely derided in England for its American tone and inept prose. An excerpt:

As for Stollop, it is safe to assert that there was not a happier man in London than he, and it would occupy no small space to relate the thoughts which filled his mind till the first rays of the morning sun peeped through the crevices of the shutters, throwing light on everything, except the mind of Stollop, as to how the night’s adventure would affect his perspective future, and how long it would be ere he should lead the beautiful young lady to the altar.

The book found an unlikely supporter in Arthur Conan Doyle, who had turned to spiritualism after a series of tragedies in his own life. “If it was a true communication,” he wrote, “it must have been intensely galling to the author that his efforts should have been met with derision. There would, however, be a certain poetic justice in the matter, as Dickens in his lifetime, even while admitting psychic happenings for which he could give no explanation, went out of his way to ridicule spiritualism, which he had never studied or understood.”

How should a tolerant person regard intolerance? If she tolerates it, then (it would seem) implicitly she accepts it. If she rejects it, then she is herself intolerant.

“The difficulty with toleration is that it seems to be at once necessary and impossible,” writes Bernard Williams. “Toleration, we may say, is required only for the intolerable. That is its basic problem.”