Inside Out

Every great work inspires variants. Here are the opening lines of Ernest Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not:

You know how it is there early in the morning in Havana with the bums still asleep against the walls of the buildings; before even the ice wagons come by with ice for the bars? Well, we came across the square from the dock to the Pearl of San Francisco café to get coffee and there was only one beggar awake in the square and he was getting a drink out of the fountain. But when we got inside the café and sat down, there were the three of them waiting for us.

We sat down and one of them came over. ‘Well,’ he said.

‘I can’t do it,’ I told him. ‘I’d like to do it as a favor. But I told you last night I couldn’t.’

‘You can name your own price.’

‘It isn’t that. I can’t do it. That’s all.’

And here are the opening lines of Lynn Crawford’s To Have Not and Have:

Few understand it here late in the evening in Oslo with the divas wide awake still opening, closing doors after even fuel company planes fly in fuel for the fires. Well, I navigated to the walkway extending from shore to the Sow’s Ear café to drop off brandy and there were several divas awake spooning meals out of bowls. But when I got inside and leaned on the bar, there was one running from me.

I continued standing and several more ran from me.

‘Hey,’ they carolled.

‘I can do it,’ I told them. ‘I told you this morning it was impossible. But I can do it for a fee.’

‘We name your fee.’

‘Agreed. I can do it. And something else –‘

This is an example of antonymy, a technique invented by the French experimental writing group Oulipo in which each designated element in a text is replaced with its opposite.

A simpler example: “To not be and to be: this was an answer.”

In a Word

aletude

n. corpulency

gundygut

n. a voracious eater

“Imprisoned in every fat man a thin one is wildly signalling to be let out.” — Cyril Connolly, The Unquiet Grave, 1944

“Outside every fat man there was an even fatter man trying to close in.” — Kingsley Amis, One Fat Englishman, 1963

Homeownership

Plumber is icumen in;

Bludie big tu-du.

Bloweth lampe, and showeth dampe,

And dripth the wud thru.

Bludie hel, boo-hoo!

Thawth drain, and runneth bath;

Saw sawth, and scruth scru;

Bull-kuk squirteth, leakë spurteth;

Wurry springeth up anew,

Boo-hoo, boo-hoo.

Tom Pugh, Tom Pugh, well plumbës thu, Tom Pugh;

Better job I naver nu.

Therefore will I cease boo-hoo,

Woorie not, but cry pooh-pooh,

Murie sing pooh-pooh, pooh-pooh,

Pooh-pooh!

— A.Y. Campbell

(Whack)

In 1877, five-year-old Bertrand Russell asked his Aunt Agatha, “Aunty, do limpets think?”

She said, “I don’t know.”

He said, “Then you must learn.”

Born Free

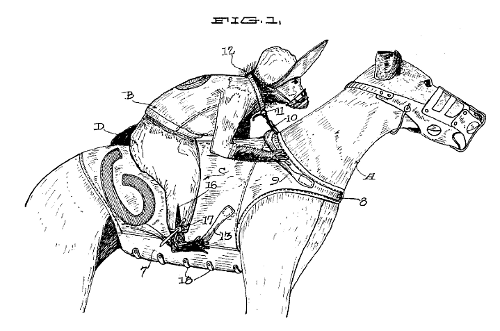

Someday archaeologists will unearth this 1933 patent abstract by Rennie Renfro and use it to judge our entire civilization:

In the sport of greyhound racing, that is enjoyed by dog fanciers and racing enthusiasts, there has been recently introduced, the use of monkey riders, who serve in the capacity of jockeys. Because of the aptitude and imitative tendencies of simians, when they are positioned on the backs of their fleet charges, they imitate the actions of regular jockeys. The employment of the monkey jockey adds considerable zest and enjoyment to the sport. However, as in horse racing, there is always present the danger of the rider being accidentally thrown, and unless some means is provided for safely securing the riders, there is ever present the hazard of the rider being dislodged, with consequent injury.

Renfro’s improvement was to snap the monkey’s collar to the harness and to strap its breeches to the saddle. “In practice the device has proven to be most efficient, humane and because of its novel construction, has added to the enthusiasm and entertainment of racing patrons.”

In the Wings

When did Shakespeare’s plays come into existence? We tend to think they appeared when he conceived them.

But if God is omniscient, then he has perfect knowledge of the future. Before the creation, he knew that Shakespeare would compose the plays, and he knew the full text of each one.

“A consequence of the view that God knows everything about the future is that all compositions existed before creation,” writes philosopher Richard R. La Croix.

In this sense, “the coming into existence of any composition is an event which occurs prior to the events that cause it to occur” — and, in each case, an effect precedes its cause.

Sold

Letter to the Times, May 19, 1932:

Sir,

I wonder if any of your male readers suffer as I do from what I can only describe as ‘Shop-shyness’? When I go into a shop I never seem to be able to get what I want, and I certainly never want what I eventually get. Take hats. When I want a grey soft hat which I have seen in the window priced at 17s. 6d. I come out with a brown hat (which doesn’t suit me) costing 35s. All because I have not the pluck to insist upon having what I want. I have got into the habit of saying weakly, ‘Yes, I’ll have that one,’ just because the shop assistant assures me that it suits me, fits me, and is a far, far better article than the one I originally asked for.

It is the same with shoes. In a shoe shop I am like clay in the hands of a potter. ‘I want a pair of black shoes,’ I say, ‘about twenty-five shillings — like those in the window.’ The man kneels down, measures my foot, produces a cardboard box, shoves on a shoe, and assures me it is ‘a nice fit.’ I get up and walk about. ‘How much are these?’ I ask. ‘These are fifty-two and six, Sir,’ he says, ‘a very superior shoe, Sir.’ After that I simply dare not ask to see the inferior shoes at 25s., which is all I had meant to pay. ‘Very well,’ I say in my weak way, ‘I’ll take these.’ And I do. I also take a bottle of cream polish, a pair of ‘gent’s half-hose,’ and some aluminium shoe-trees which the fellow persuades me to let him pack up with the shoes. I have made a mess of my shopping as usual.

Is there any cure for ‘shop-shyness’? Is there any ‘Course of Shopping Lessons’ during which I could as it were ‘Buy while I Learned’? If so I should like to hear of it. For I have just received a price list of ‘Very Attractive Gent’s Spring Suitings,’ and I am afraid — yes I am afraid … !

I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

W. Hodgson Burnet

Tilt Shift

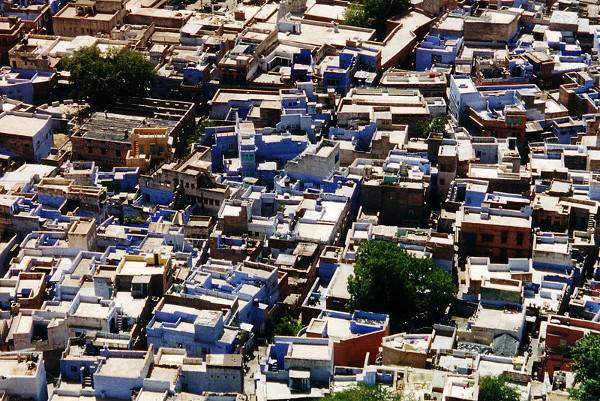

Above is a photo of the Indian city of Jodhpur. Below, seemingly, is a detailed scale model of the same scene.

In fact it’s the same photo, altered so that the foreground and background are out of focus. This narrow depth of field is most familiar from close-up photographs of miniature scenes, so the eye assumes that’s what it’s seeing.

Unquote

“Men are not hang’d for stealing Horses, but that Horses may not be stolen.” — George Savile, Marquess of Halifax