analphabet

n. one who cannot read

Upstanding

Abraham Lincoln’s former law partner, William Henry Herndon, published a biography of the president in 1889. While gathering material for the project, he received this letter from a colleague:

Dear Herndon:

One morning, not long before Lincoln’s nomination — a year perhaps — I was in your office and heard the following: Mr. Lincoln, seated at the baize-covered table in the center of the office, listened attentively to a man who talked earnestly and in a low tone. After being thus engaged for some time Lincoln at length broke in, and I shall never forget his reply. ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘we can doubtless gain your case for you; we can set a whole neighborhood at loggerheads; we can distress a widowed mother and her six fatherless children and thereby get for you six hundred dollars to which you seem to have a legal claim, but which rightfully belongs, it appears to me, as much to the woman and her children as it does to you. You must remember that some things legally right are not morally right. We shall not take your case, but will give you a little advice for which we will charge you nothing. You seem to be a sprightly, energetic man; we would advise you to try your hand at making six hundred dollars in some other way.’

Yours,

Lord

The Paradox of the Second Ace

You’re watching four statisticians play bridge. After a hand is dealt, you choose a player and ask, “Do you have at least one ace?” If she answers yes, the chance that she’s holding more than one ace is 5359/14498, which is less than 37 percent.

On a later hand, you choose a player and ask, “Do you have the ace of spades?” Strangely, if she says yes now the chance that she has more than one ace is 11686/20825, which is more than 56 percent.

Why does specifying the suit of her ace improve the odds that she’s holding more than one ace? Because, though a smaller number of potential hands contain that particular ace, a greater proportion of those hands contain a second ace. It’s counterintuitive, but it’s true.

Modern Convenience

For the stylish farmer, Jefferson Darby patented this plow attachment in 1874. The canopy can be adjusted both horizontally and vertically, “thus affording a complex and ample range of adjustment by which the shade may be shifted about as the plow changes direction and the sun moves along its course.”

“The attachment may also be attached to other agricultural implements, also upon wagons and other carriages.”

The Vision Thing

Diary entry by journalist Sydney Moseley, Aug. 1, 1928:

… I met a pale young man named Bartlett who is Secretary to the new Baird Television Company. Television! Anxious to see what it is all about … He invited me to go along to Long Acre where the new invention is installed. Now that’s something! Television!

Met John Logie Baird; a charming man — a shy, quietly spoken Scot. He could serve as a model for the schoolboy’s picture of a shock-haired, modest, dreamy, absent-minded inventor. Nevertheless shrewd. We sat and chatted. He told me he is having a bad time with the scoffers and skeptics — including the BBC and part of the technical press — who are trying to ridicule and kill his invention of television at its inception. I told him that if he would let me see what he has actually achieved — well, he would have to risk my damning it — or praising it! If I were convinced — I would battle for him. We got on well together and I have arranged to test his remarkable claim.

(Later) Saw television! Baird’s partner, a tall, good-looking but highly temperamental Irishman, Captain Oliver George Hutchinson, was nice but very nervous of chancing it with me. He was terribly anxious that I should be impressed. Liked the pair of them, especially Baird, and decided to give my support … I think we really have what is called television. And so, once more into the fray!

The Lodging-House Difficulty

A puzzle by Henry Dudeney:

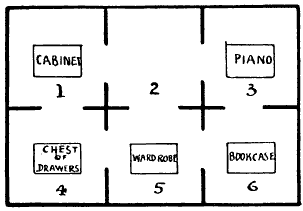

The Dobsons secured apartments at Slocomb-on-Sea. There were six rooms on the same floor, all communicating, as shown in the diagram. The rooms they took were numbers 4, 5, and 6, all facing the sea.

But a little difficulty arose. Mr. Dobson insisted that the piano and the bookcase should change rooms. This was wily, for the Dobsons were not musical, but they wanted to prevent any one else playing the instrument.

Now, the rooms were very small and the pieces of furniture indicated were very big, so that no two of these articles could be got into any room at the same time. How was the exchange to be made with the least possible labour? Suppose, for example, you first move the wardrobe into No. 2; then you can move the bookcase to No. 5 and the piano to No. 6, and so on.

It is a fascinating puzzle, but the landlady had reasons for not appreciating it. Try to solve her difficulty in the fewest possible removals with counters on a sheet of paper.

A Change of Key

5 × 55 × 555 = 152625

remains true if each digit is increased by 1:

6 × 66 × 666 = 263736

Long Time Coming

One day I was out milking the cows. Mr. Dave come down into the field, and he had a paper in his hand. ‘Listen to me, Tom,’ he said, ‘listen to what I reads you.’ And he read from a paper all about how I was free. You can’t tell how I felt. ‘You’re jokin’ me.’ I says. ‘No, I ain’t,’ says he. ‘You’re free.’ ‘No,’ says I, ‘it’s a joke.’ ‘No,’ says he, ‘it’s a law that I got to read this paper to you. Now listen while I read it again.’

But still I wouldn’t believe him. ‘Just go up to the house,’ says he, ‘and ask Mrs. Robinson. She’ll tell you.’ So I went. ‘It’s a joke,’ I says to her. ‘Did you ever know your master to tell you a lie?’ she says. ‘No,’ says I, ‘I ain’t.’ ‘Well,’ she says, ‘the war’s over and you’re free.’

By that time I thought maybe she was telling me what was right. ‘Miss Robinson,’ says I, ‘can I go over to see the Smiths?’ — they was a colored family that lived nearby. ‘Don’t you understand,’ says she, ‘you’re free. You don’t have to ask me what you can do. Run along, child.’

And so I went. And do you know why I was a-going? I wanted to find out if they was free too. I just couldn’t take it all in. I couldn’t believe we was all free alike.

Was I happy? Law, miss. You can take anything. No matter how good you treat it — it wants to be free. You can treat it good and feed it good and give it everything it seems to want — but if you open the cage — it’s happy.

— Former slave Tom Robinson, 88, of Hot Springs, Ark., interviewed by the Federal Writers’ Project for the Slave Narrative Collection of 1936-38

Brunnian Links

The standard braid has a curious property: If we remove any one of the three strands, the other two are seen to be unconnected. If we remove the black strand above, the blue and red strands simply snake along one above the other. Similarly, removing the red or the blue strand reveals that the remaining strands are not braided together.

See Borromean Rings.

Unquote

“An adventure is only an inconvenience rightly considered. An inconvenience is an adventure wrongly considered.” — G.K. Chesterton, “On Running After One’s Hat,” 1908