Two runners start from the same point on a circular track and run at different constant speeds. If they run in opposite directions on the track, they meet after a minute. If they run in the same direction, they meet after an hour. What’s the ratio of their speeds?

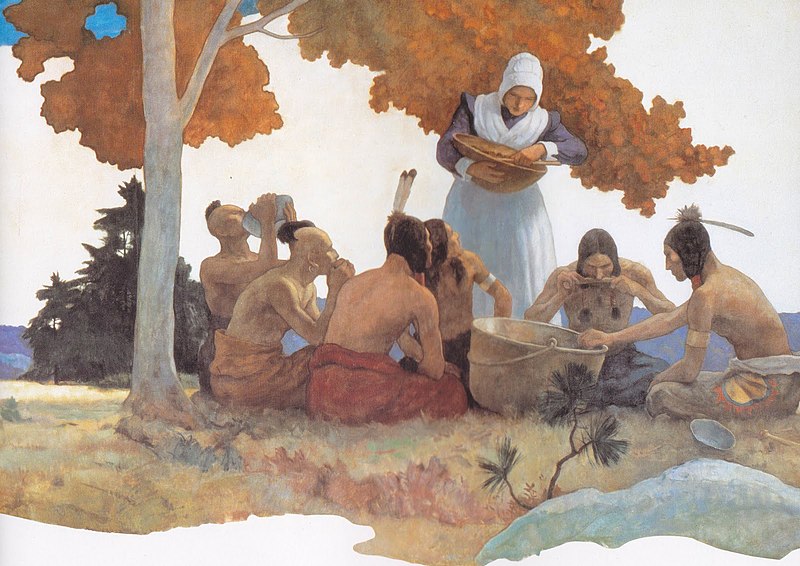

Hospitality

A year ago my older son brought home a program printed by his school; on the second page was an illustration of the ‘First Thanksgiving,’ with a caption which read in part: ‘They served pumpkins and turkeys and corn and squash. The Indians had never seen such a feast!’

On the contrary! The Pilgrims had literally never seen ‘such a feast,’ since all foods mentioned are exclusively indigenous to the Americas and had been provided by [or with the aid of] the local tribe.

— Michael Dorris, “Why I’m Not Thankful for Thanksgiving,” in Bill Bigelow and Bob Peterson, eds., Rethinking Columbus: The Next 500 Years, 1998

Economy

In an office the boy owed one of the clerks threepence, the clerk owed the cashier twopence, and the cashier owed the boy twopence. One day the boy, having a penny, decided to diminish his debt, and gave the penny to the clerk, who in turn paid half his debt by giving it to the cashier, the latter gave it back to the boy, saying, ‘That makes one penny I owe you now;’ the office boy again passed it to the clerk, who passed it to the cashier, who in turn passed it back to the boy, and the boy discharged his entire debt by handing it over to the clerk, thereby squaring all accounts.

— John Scott, The Puzzle King, 1899

Lexicon

Words that don’t exist but ought to, proposed by Gelett Burgess in Burgess Unabridged (1914):

cowcat: an unimportant guest, an insignificant personality

critch: to array oneself in uncomfortable splendor

edicle: one who is educated beyond his intellect, a pedant

fidgeltick: food that is a bore to eat

flooijab: an apparent compliment with a concealed sting

gloogo: foolishly faithful without reward

gorgule: a splendiferous, over-ornate object or gift

gowyop: a perplexity wherein familiar things seem strange

jip: a dangerous subject of conversation

lallify: to prolong a story tiresomely, or repeat a joke

leolump: an interrupter of conversations

oofle: a person whose name one cannot remember

paloodle: to give unnecessary advice

pooje: a regrettable discovery

spillix: accidental good luck

tashivation: the art of answering without listening to questions

uglet: an unpleasant duty too long postponed

vorge: voluntary suffering, unnecessary effort or exercise

xenogore: an interloper who keeps one from interesting things

yamnoy: a bulky, unmanageable object to be carried

yowf: one whose importance exceeds his merit

Interestingly, we owe the word blurb to Burgess — he invented it in 1906 for his book Are You a Bromide?, and it proved so useful that we’re still using it more than a century later.

Balancing Act

The Devil’s Table is a startling rock formation 14 meters high in Germany’s Palatine Forest. A layer of hard siliceous sandstone was deposited atop a softer sediment that then weathered away, leaving a “tabletop” that protects its pillar from further erosion. It was classified as a National Geotope in 2006.

Tilt

Hinchliffe’s rule, named after physicist Ian Hinchliffe, states that if the title of a scholarly article takes the form of a yes-no question, the answer to that question will be no.

In 1988 Boris Peon tested this proposition by writing a paper titled “Is Hinchliffe’s Rule True?”:

Hinchliffe has asserted that whenever the title of a paper is a question with a yes/no answer, the answer is always no. This paper demonstrates that Hinchliffe’s assertion is false, but only if it is true.

This seems to threaten the integrity of the universe. Happily, Harvard computer scientist Stuart Shieber pointed out that Hinchliffe’s rule might simply be false, in which case Peon’s title presents no problem.

Unfortunately Shieber also managed to resurrect the paradox by titling his article “Is This Article Consistent With Hinchliffe’s Rule?”

We await developments.

Still Life

Wiio’s Laws

Finnish economist and parliamentarian Osmo Antero Wiio framed these rueful principles of human communication in 1978:

- Communication usually fails, except by accident.

- If communication can fail, it will.

- If communication cannot fail, it still most usually fails.

- If communication seems to succeed in the intended way, there’s a misunderstanding.

- If you are content with your message, communication certainly fails.

- If a message can be interpreted in several ways, it will be interpreted in a manner that maximizes the damage.

- There is always someone who knows better than you what you meant with your message.

- The more we communicate, the worse communication succeeds.

- The more we communicate, the faster misunderstandings propagate.

- In mass communication, the important thing is not how things are but how they seem to be.

- The importance of a news item is inversely proportional to the square of the distance.

- The more important the situation is, the more probable you had forgotten an essential thing that you remembered a moment ago.

Writer Jukka Korpela offered two corrolaries: “If nobody barks at you, your message did not get through” and “Search for information fails, except by accident.”

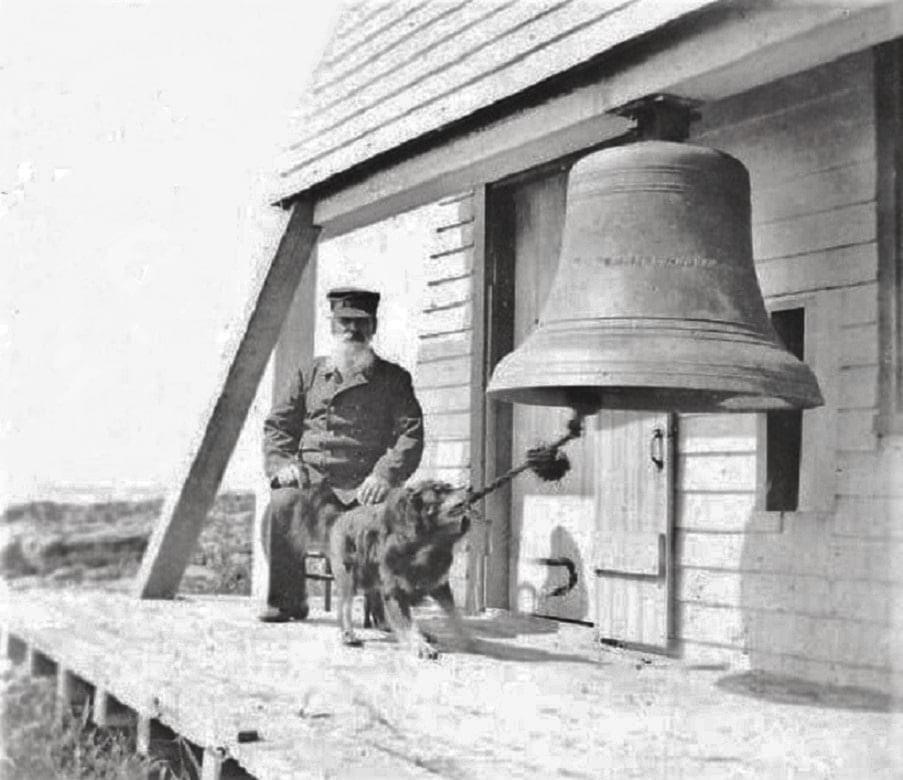

In a Word

obeliscolychny

n. a lighthouse

morsure

n. the act of biting

salvediction

n. salutation on meeting

grandisonant

adj. stately-sounding

In 1900, a collie on Wood Island in Saco Bay, Maine, gained international fame for ringing the lighthouse’s fog bell to greet passing ships. “When ‘Sailor,’ for that is what he is called, sees a vessel passing the lighthouse he runs to the bell, and with a quick, sharp bark seizes the short rope between his teeth and rings several times,” wrote a correspondent to the Strand.

“As the years have passed ‘Sailor’ has kept on ringing salutes to passing vessels and steamers,” observed the Boston Herald. “Indeed, he feels hurt if not permitted to give the customary salute to passing craft, while skippers whose course takes them often past Wood Island are accustomed to see ‘Sailor’ tugging viciously at the bell rope. They reply with a will on their ship’s bell or horn, and in case of steamers a hearty triple blast is sent back to the watcher of Wood Island, who gives a new meaning to the good old sea term of ‘dog watch.'”

(Thanks, Frank.)

No Time Like the Present

In Surprised by Joy, C.S. Lewis points out a phenomenon he calls “chronological snobbery,” “the uncritical acceptance of the intellectual climate common to our own age and the assumption that whatever has gone out of date is on that account discredited”:

You must find why it went out of date. Was it ever refuted (and if so by whom, where, and how conclusively) or did it merely die away as fashions do? If the latter, this tells us nothing about its truth or falsehood. From seeing this, one passes to the realization that our own age is also ‘a period,’ and certainly has, like all periods, its own characteristic illusions. They are likeliest to lurk in those widespread assumptions which are so ingrained in the age that no one dares to attack or feels it necessary to defend them.

“History does not always repeat itself,” wrote John W. Campbell. “Sometimes it just yells, ‘Can’t you remember anything I told you?’ and lets fly with a club.”