“I think, therefore I am is the statement of an intellectual who underrates toothaches.” — Milan Kundera

“I think, therefore I am is the statement of an intellectual who underrates toothaches.” — Milan Kundera

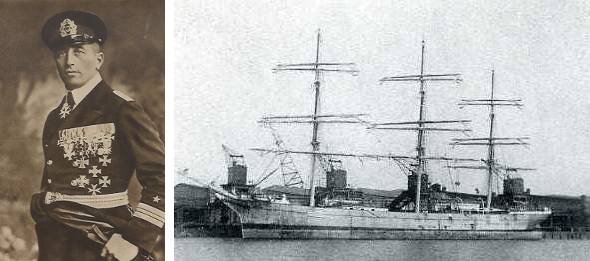

When Germany was blockaded by the British in 1916, naval officer Felix von Luckner hit on a dashing solution: He outfitted a three-masted sailing ship, the Seeadler, with hidden guns and engines and crept through the cordon posing as a humble Norwegian wood carrier. Once safely at sea he spent the ensuing year as a sort of humanitarian pirate, sinking one merchant ship after another while imprisoning their crews and leading the British and American navies on a merry chase. Over 225 days he captured some 16 ships and 300 prisoners with nearly no loss of life (one British sailor was killed by a ruptured steam pipe). The Seeadler was finally wrecked on a reef in August 1917, and Von Luckner spent the rest of the war in a New Zealand prisoner-of-war camp.

In the interval he returned a measure of romance to naval warfare, giving his “guests” run of the ship and even permitting captured cooks to prepare meals in their native cuisines. “When he discovered, after sinking the [Canadian schooner] Percy, that he had interrupted a honeymoon, he was most contrite and gave the Kohlers a cabin to themselves, remarking that he was desolated at having had to sink their ship,” writes John Philips Cranwell in Spoilers of the Sea. “Captain Kohler’s remarks on the subject are not, unfortunately, available.”

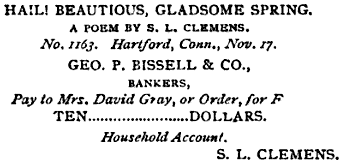

Mark Twain once entered a contest that offered $10 for the best original poem on the topic of spring, “no poem to be considered unless it should possess positive value.” He submitted this:

“It took the prize for this reason, no other poem offered was really worth more than $4.50, whereas there was no getting around the petrified fact that this one was worth $10. In truth there was not a banker in the whole town who was willing to invest a cent in those other poems, but every one of them said this one was good, sound, seaworthy poetry, and worth its face. … Let other struggling young poets be encouraged by this to go striving.”

See Inspiration.

In 1919, the mother of 9-year-old Samuel Barber found this letter on his desk:

NOTICE to Mother and nobody else

Dear Mother: I have written this to tell you my worrying secret. Now don’t cry when you read it because it is neither yours nor my fault. I suppose I will have to tell it now without any nonsense. To begin with I was not meant to be an athlet [sic]. I was meant to be a composer, and will be I’m sure. I’ll ask you one more thing. — Don’t ask me to try to forget this unpleasant thing and go play football. — Please — Sometimes I’ve been worrying about this so much that it makes me mad (not very)

Love,

Sam Barber II

Here’s a familiar idea — in 1820 an enterprising Englishman advertised “an establishment where persons of all classes who are anxious to sweeten life by repairing to the altar of Hymen, have an opportunity of meeting with proper partners.” If you were seeking a mate you’d sign up by a paying a fee according to your desirability; the handbill gives these rather blunt examples:

Ladies.

1st Class. I am twenty years of age, heiress to an estate in the county of Essex of the value of 30,000l., well educated, and of domestic habits; of an agreeable, lively disposition, and genteel figure. Religion that of my future husband.

2nd Class. I am thirty years of age, a widow, in the grocery line in London — have children; of middle stature, full made, fair complexion and hair, temper agreeable, worth 3,000l.

3rd Class. I am tall and thin, a little lame in the hip, of a lively disposition, conversible, twenty years of age, live with my father, who, if I marry with his consent, will give me 1,000l.

4th Class. I am twenty years of age; mild disposition and manners; allowed to be personable.

5th Class. I am sixty years of age; income limited; active, and rather agreeable.Gentlemen.

1st Class. A young gentleman with dark eyes and hair; stout made; well educated; have an estate of 500l. per annum in the county of Kent; besides 10,000l. in three per cent. consolidated annuities; am of an affable disposition, and very affectionate.

2nd Class. I am forty years of age, tall and slender, fair complexion and hair, well tempered and of sober habits, have a situation in the Excise, of 300l. per annum, and a small estate in Wales of the annual value of 150l.

3rd Class. A tradesman in the city of Bristol, in a ready-money business, turning 150l. per week at a profit of 10 per cent., pretty well tempered, lively, and fond of home.

4th Class. I am fifty-eight years of age; a widower, without encumbrance; retired from business upon a small income ; healthy constitution; and of domestic habits.

5th Class. I am twenty-five years of age; a mechanic of sober habits; industrious, and of respectable connections.

“The subscribers are to be furnished with a list of descriptions, and when one occurs likely to suit, the parties may correspond; and if mutually approved, the interview may be afterwards arranged.”

I can’t tell how well it succeeded. “It is presumed that the public will not find any difficulty in describing themselves; if they should, they will have the assistance of the managers, who will be in attendance at the office, No. 5, Great St. Helens, Bishopsgate Street, on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, between the hours of eleven and three o’clock. — Please to inquire for Mr. Jameson, up one pair of stairs. All letters to be post paid.”

(From Henry Sampson, A History of Advertising from the Earliest Times, 1875.)

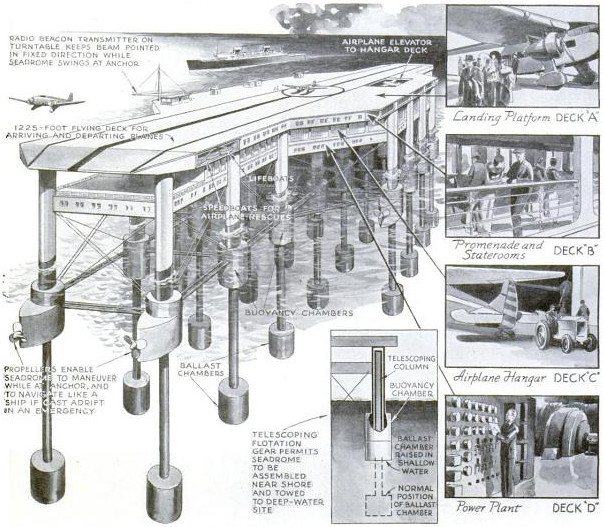

In 1927, before the advent of long-range aircraft, engineer Edward R. Armstrong proposed a unique way to get across the ocean: floating airports. Armstrong’s “seadromes” would stand above the waves on columns of steel, tethered to the ocean floor and stabilized with ballast tanks. Atop each would be a 1200-foot runway, a hotel, a restaurant, a hangar, and a fuel depot, effectively turning it into a stationary aircraft carrier. Armstrong hoped to string eight of these across the Atlantic so that short-range planes could hop between America and Europe.

He managed to interest the U.S. government in the scheme, and in 1934 Popular Science reported that lawyers had built a case for anchoring the stations on the high seas. But the Depression and the appearance of transatlantic aircraft finally crippled the plan, and Armstrong’s dream was never realized. The principle he proposed survives in floating oil rigs.

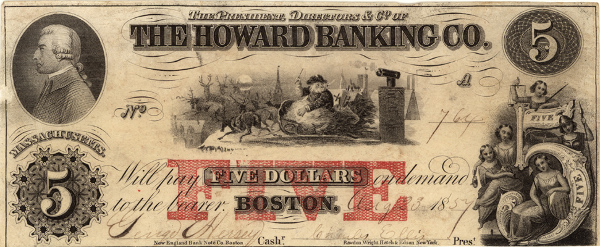

The U.S. government did not issue paper money until 1861. Until then, private banks printed their own currency under charters to the states.

As a result, this $5 bill featuring Santa Claus was legal tender in the 1850s. It was issued by the Howard Banking Company of Boston.

A number of banks issued Santa-themed money in the same period — the most natural being the St. Nicholas Bank of New York City.

peccable

adj. liable to sin