You’re alone on a desert island and want to lay out a course for some snail races. Unfortunately, you have only an 8.5 x 11 inch sheet of paper. How can you use it to measure exactly 3 inches?

You’re alone on a desert island and want to lay out a course for some snail races. Unfortunately, you have only an 8.5 x 11 inch sheet of paper. How can you use it to measure exactly 3 inches?

On Tuesday week, as the coal train on the Swannington line was proceeding to Leicester, and when near Glenfield, the engine-driver suddenly perceived a fine bullock appear on the line, and turn to meet the train, head to head with the engine. The animal ran directly up to its fiery antagonist, and by the contact was killed on the spot. There was no time to stop the train before the infuriated beast came up. It was afterwards discovered that the animal belonged to Mr. Hassell, of Glenfield, and made its way on to the line from the field adjoining.

— Leicester Journal, reprinted in the Times, Aug. 10, 1849

You and a friend are playing a game. Between you is a pile of 15 pennies. You’ll take turns removing pennies from the pile — each of you, on his turn, can choose to remove 1, 2, or 3 pennies. The loser is the one who removes the last penny.

You go first. How should you play?

When the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge University instituted an annual dinner in 1897, it began a tradition of “postprandial proceedings” — typically songs sung around a piano. This air, “Ions Mine,” was sung to the tune of “Clementine”:

In the dusty lab’ratory,

‘Mid the coils and wax and twine,

There the atoms in their glory

Ionize and recombine.

(chorus) Oh my darlings! Oh my darlings!

Oh my darling ions mine!

You are lost and gone forever

When just once you recombine!

In a tube quite electrodeless,

They discharge around a line,

And the glow they leave behind them

Is quite corking for a time.

(repeat chorus)

And with quite a small expansion,

1.8 or 1.9,

You can get a cloud delightful,

Which explains both snow and rain.

(repeat chorus)

In the weird magnetic circuit

See how lovingly they twine,

As each ion describes a spiral

Round its own magnetic line.

(repeat chorus)

Ultra-violet radiation

From the arc of glowing lime,

Soon discharges a conductor

If it’s charged with minus sign.

(repeat chorus)

Alpha rays from radium bromide

Cause a zinc-blende screen to shine,

Set it glowing, clearly showing

Scintillations all the time.

(repeat chorus)

Radium bromide emanation,

Rutherford did first divine,

Turns to helium, then Sir William

Got the spectrum, every line.

(repeat chorus)

The fourth verse was contributed by J.J. Thomson himself.

I release a fish at the edge of a circular pool. It swims 80 feet in a straight line and bumps into the wall. It turns 90 degrees, swims another 60 feet, and hits the wall again. How wide is the pool?

William Dean Howells to Mark Twain, Nov. 5, 1875:

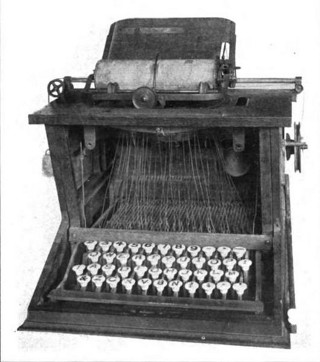

The type-writer came Wednesday night, and is already beginning to have its effect on me. Of course it doesn’t work: if I can persuade some of the letters to get up against the ribbon they won’t get down again without digital assistance. The treadle refuses to have any part or parcel in the performance; and I don’t know how to get the roller to turn with the paper. Nevertheless I have begun several letters to My d ar lemans, as it prefers to spell your respected name, and I don’t despair yet of sending you something in its beautiful handwriting–after I’ve had a man out from the agent’s to put it in order. It’s fascinating in the meantime, and it wastes my time like an old friend.

E.B. White on the Model T, 1936:

During my association with Model Ts, self-starters were not a prevalent accessory. They were expensive and under suspicion. Your car came equipped with a serviceable crank, and the first thing you learned was how to Get Results. It was a special trick, and until you learned it (usually from another Ford owner, but sometimes by a period of appalling experimentation) you might as well have been winding up an awning. The trick was to leave the ignition switch off, proceed to the animal’s head, pull the choke (which was a little wire protruding through the radiator) and give the crank two or three nonchalant upward lifts. Then, whistling as though thinking about something else, you would saunter back to the driver’s cabin, turn the ignition on, return to the crank, and this time, catching it on the down stroke, give it a quick spin with plenty of that. If this procedure was followed, the engine almost always responded — first with a few scattered explosions, then with a tumultuous gunfire, which you checked by racing around to the driver’s seat and retarding the throttle. Often, if the emergency brake hadn’t been pulled all the way back, the car advanced on you the instant the first explosion occurred and you would hold it back by leaning your weight against it. I can still feel my old Ford nuzzling me at the curb, as though looking for an apple in my pocket.

In December 1930, 26-year-old British meteorologist Augustine Courtauld volunteered to man an observation station alone in the interior of Greenland. He passed the winter well enough, but his relief party was thrice delayed, and by late March Courtauld’s station was entirely buried in snow. He would spend the next six weeks immured in his hut, above which only the Union Jack projected, and husbanding his dwindling supplies. Most of the time he simply lay in the dark, but occasionally he would light a candle to write in his journal or to read his sweetheart Mollie’s last letter. At one point he listed the pleasures he would “like to have granted if wishing were any good”:

By May 1 he was out of food and was burning ski wax for light. Five days later, the stove that he used to melt drinking water had just died when “suddenly there was an appalling noise like a bus going by, followed by a confused yelling noise. I nearly jumped out of my skin. Was it the house falling in at last? A second later I realised the truth. It was somebody, some real human voice, calling down the ventilator.”

They pulled him out through the roof and he rode back to the coast on a sledge, reading The Count of Monte Cristo in the sun. He went on to fulfill all of the New Year’s resolutions he had made on the ice cap: to marry Mollie, to buy a house and a boat, to collect a library, and to give up exploring.

A youth, the son of Mr. Richard Bolton, of Great Horton, Yorkshire, was playing a few days since with a juvenile companion, who was pretending to place a pea in his ear and to make it come out of his mouth. Bolton, believing the feat to have been really performed, was induced to make the attempt himself, and thrust the pea so far into his ear that it could not be got out. In a vain endeavour to extract it made by a medical man, it was sent further in, and the poor boy died four days afterwards from the effects.

— Times, Nov. 27, 1850

In the burying-ground at Newburyport, may be seen a stone inscribed:

Omnem Crede Dicum Tibi Diluxesse Supremum.

Sacred to the memory of Mrs. Mary M’Hard, the virtuous and amiable consort of Capt. Wm. M’Hard of Newburyport, who amidst the laudable exertions of a very useful and desirable life, in which her Christian Profession was well adorned and a fair copy of every social virtue displayed, was in a state of health suddenly summoned to the Skies and snatched from ye eager embraces of her friends, (and the throbbing breasts of her disconsolate family confessed their fairest prospects of sublinary bliss were in one moment dashed) by swallowing a Pea at her own table, whence in a few hours, she sweetly breathed her soul away unto her SAVIOUR’S arms on the 8th day of March, A. D. 1780.

Ætatis 47.

— John Robert Kippax, Churchyard Literature, 1877

satanophany

n. a visible manifestation of Satan

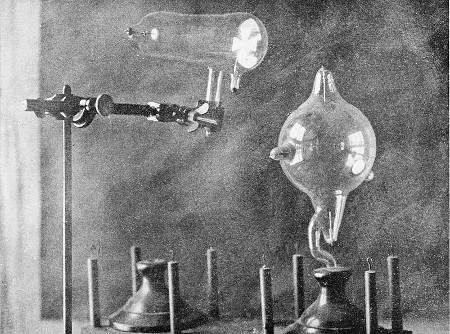

Potassium chlorate brings out the worst in gummy bears.

In their 1996 manual Chemical Curiosities, H.W. Roesky and K. Möckel introduce this demonstration with an invocation from the Talmud: “He who ponders long over four things were better never to have been born: that which is above, that which is below, that which came before, and that which comes hereafter.”

(Please don’t try this yourself.)