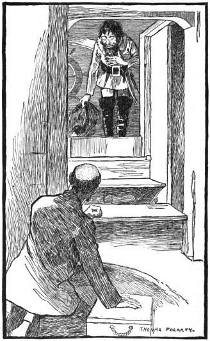

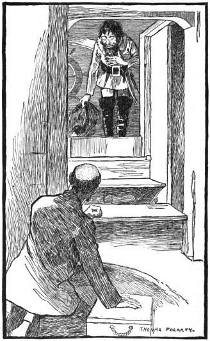

Sailing past the Azores on his solo circumnavigation of 1895-98, Joshua Slocum ate some bad plums and collapsed with cramps in his cabin. He awoke from a fever to find that he was not alone.

“I saw a tall man at the helm. His rigid hand, grasping the spokes of the wheel, held them as in a vise. One may imagine my astonishment. His rig was that of a foreign sailor, and the large red cap he wore was cockbilled over his left ear, and all was set off with shaggy black whiskers. He would have been taken for a pirate in any part of the world.”

“I have come to do you no harm,” the stranger told him. “I have sailed free, but was never worse than a contrabandista. I am one of Columbus’s crew. I am the pilot of the Pinta come to aid you. Lie quiet, señor captain, and I will guide your ship to-night. You have a calentura, but you will be all right to-morrow.”

Slocum drifted out of consciousness, but he awoke in the morning to find that the Spray had made 90 miles that night on a true course through a rough sea. As he lay on deck that day, the man revisited him in a dream. “You did well last night to take my advice,” he said, “and if you would, I should like to be with you often on the voyage, for the love of adventure alone.”

“I awoke much refreshed, and with the feeling that I had been in the presence of a friend and a seaman of vast experience,” Slocum wrote. “I gathered up my clothes, which by this time were dry, then, by inspiration, I threw overboard all the plums in the vessel.”