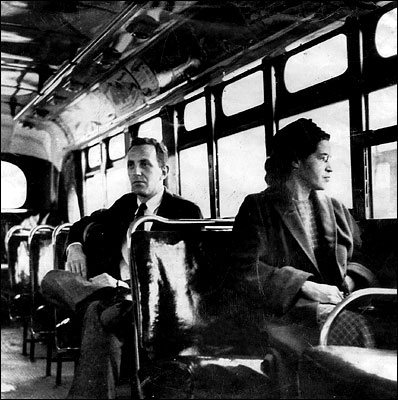

Kindergartners recount Rosa Parks’ story, from Vivian Paley’s 1981 collection Wally’s Stories:

Wally: My mom said Martin Luther King was smart and he decided about having white people to sit in the front and black people in the back. Wait! That was what they decided. And then he decided to throw off that sign and so you could sit anywhere.

Eddie: You forgot to say about Rosa Parks. See, she came on the bus and gave the bus driver some money and she sat in the chair and the bus driver said, “No, you’re not white.” And she said, “I don’t care. I want to sit because I’m tired and also I gave you a dime.” Was it a dime or a nickel?

Tanya: Maybe a quarter.

Eddie: Maybe a dime. So she said, “I’m not going to leave.” So they put her in jail.

Wally: Now you can sit wherever you want. Also Martin wasn’t allowed to go to any water fountain or any bathroom and he also had to have only a black grocery-store man to pay. He was separated. My mom knows all about that. She even used to be separated. …

Jill: That reminds me. Why do we have to always sit at the same lunch table?

Teacher: What would you rather do?

Jill: Sit anywhere we want. That’s more fair.

Teacher: That might become confusing. Most people would rather know exactly where they sit, Jill.

Deana: I don’t would rather know.

Eddie: Me neither.

Teacher: How does everyone else feel about this? [There is unanimous approval.] Well, then, it’s okay with me.

Jill: Free at last!