“Sleep is death enjoyed.” — Friedrich Hebbel

“Sleep is death enjoyed.” — Friedrich Hebbel

Moscow’s stray dogs have begun using the city’s subway system. Zoologist Andrey Poyarkov of the Moscow Ecology and Evolution Institute, who has been studying the city’s 35,000 strays for 30 years, says some dogs scavenge downtown during the day and board trains in the evening to travel to industrial complexes in the suburbs, where they sleep.

“Because the best scavenging for food is in the city center,” Poyarkov told the Sun, “the dogs had to learn how to travel on the subway — to get to the center in the morning, then back home in the evening, just like people.”

This seems to be a sinister trend:

It gets worse: Poyarkov’s graduate student Alexei Vereshchagin says that stray dogs in Moscow have been observed obeying traffic lights.

When I am dead you’ll find it hard,

Said he,

To ever find another man

Like me.

What makes you think, as I suppose

You do,

I’d ever want another man

Like you?

— Eugene Fitch Ware, Some of the Rhymes of Ironquill, 1900

Put the integers 1, 2, 3, … n in any order and call them a1, a2, a3, … an. Then form the product

P = (a1 – 1) × (a2 – 2) × (a3 – 3) … × (an – n).

Now: If n is odd, prove that P is even.

I don’t know what to make of this — on Sept. 7, 1950, the London Times reported that a 10-month-old kitten had climbed the Matterhorn.

The story, “from our correspondent,” claims that the black-and-white kitten lived in the Hotel Belvedere at 10,820 feet, where he would watch departing alpinists as they left for the summit. One morning, apparently, he decided to follow them. “After a long and lonely climb” he reached the Solway hut at 12,556 feet, and the next day “bivouacked in a couloir above the shoulder.” A climbing party passed him on the third day, and he caught them up at the summit (14,780 feet), “miauing and tail up,” and was rewarded with a share of their meal. He was carried back down in a rucksack.

This is all reported very earnestly, and there’s even a photograph of the cat, but I can’t find a corroborating account anywhere. Both The Canadian Nurse and The Veterinary Record picked up the story, but they both credit the Times. The Guinness Book of World Records cited the cat for its feat, but presumably they’re relying on the same account.

Is this preposterous? Do I overestimate the Matterhorn? Do I underestimate kittens? Can anyone shed any light on this?

perpilocutionist

n. one who expounds on a subject of which he has little knowledge

In 1983, Jacob Henderson was convicted of burglarizing a Maaco paint shop in Jackson, Miss. He appealed on the ground that the indictment was illiterate:

The Grand Jurors for the State of Mississippi, … upon their oaths present: That Jacob Henderson … on the 15th day of May, A.D., 1982.

The store building there situated, the property of Metro Auto Painting, Inc., … in which store building was kept for sale or use valuable things, to-wit: goods, ware and merchandise unlawfully, feloniously and burglariously did break and enter, with intent the goods, wares and merchandise of said Metro Auto Painting then and there being in said store building unlawfully, feloniously and then and there being in said store building burglariously to take, steal and carry away; And

One (1) Polaroid Land Camera,

One (1) Realistic AM/FM Stereo Tuner

One (1) Westminster AM/FM radio

One (1) Metal Box and contents thereof,… the property of the said Metro Auto Painting then and there being in said store building did then and there unlawfully, feloniously and burglariously take, steal and carry away the aforesaid property, he, the said Jacob Henderson, having been twice previously convicted of felonies, to-wit: … .

Henderson called an English teacher as an expert witness. She pointed out that the district attorney’s indictment doesn’t charge Henderson with any wrongdoing; instead it charges the merchandise itself with breaking into the paint store.

“This case presents the question whether the rules of English grammar are a part of the positive law of this state,” wrote Justice Robertson for the court. “If they are, Jacob Henderson’s burglary conviction must surely be reversed, for the indictment in which he has been charged would receive an ‘F’ from every English teacher in the land.”

“Though grammatically unintelligible, we find that the indictment is legally sufficient and affirm, knowing full well that our decision will receive of literate persons everywhere opprobrium as intense and widespread as it will be deserved.”

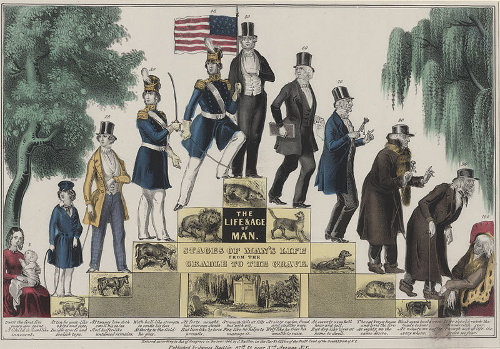

“The whole scheme of things is turned wrong end to. Life should begin with age & its privileges and accumulations, & end with youth & its capacity to splendidly enjoy such advantages. As things are now, when in youth a dollar would bring a hundred pleasures, you can’t have it. When you are old, you get it & there is nothing worth buying with it then. It’s an epitome of life. The first half of it consists of the capacity to enjoy without the chance; the last half consists of the chance without the capacity.”

— Mark Twain, letter to Edward Dimmitt, July 19, 1901