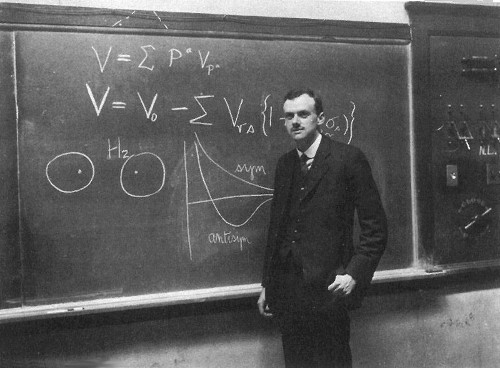

While a student at Cambridge, Paul Dirac attended a mathematical congress that posed the following problem:

After a big day’s catch, three fisherman go to sleep next to their pile of fish. During the night, one fisherman decides to go home. He divides the fish in three and finds that this leaves one extra fish. He throws this into the water, takes one third of the remaining fish, and departs.

The second fisherman awakes. Not knowing that the first has left, he too divides the fish into three piles, finds one fish left over, discards it, and takes a third of the remainder. The third fisherman does the same. What is the least number of fish that the fishermen could have started with?

Dirac proposed that they had begun with -2 fish. The first fisherman threw one into the water, leaving -3, and took a third of this, leaving -2. The second and third fisherman followed suit.

This story was recalled by “a well-meaning experimenter” in the Russian miscellany Physicists Continue to Laugh (1968). “I could tell many other stories about theoreticians and their work,” he wrote, “but they have told me that one theoretician is writing a story under the title ‘How Experimental Physicists Work.’ That, of course, will be presented upside down.”