Round Numbers

Letter to the Times, June 17, 1978:

Sir,

It is not only dates that make nice patterns of numbers. Some years ago I was bringing a Destroyer home from the Far East and was required to report my position twice a day.

One evening, I saw that we would be passing close to where the Greenwich Meridian cuts the Equator so arranged to arrive there dead on midnight. Once there I altered course to due North and stopped engines so my position signal read:

At 0000 my position Latitude 00°00’N, Longitude 00°00’E. Course 000°. Speed 0.

I had considered saying I was Nowhere but thought (probably correctly) that Their Lordships would not be amused.

Yours faithfully,

Claud Dickens

The St. Albans Raid

In October 1864, a score of young men drifted into St. Albans, a little Vermont town just south of the Canadian border. They arrived in small groups by train and coach, took rooms in local hotels, and began to pass time around town, observing the daily routines of the citizens.

On October 19, they simultaneously held up three local banks. There they revealed themselves to be Confederate soldiers, and as they collected the money they required the bank officers to take an oath of fealty to the South. Then they made off across the border. “They must have either had a guide who was acquainted with the road or had made a personal examination,” wrote one investigator, “because there were places in the road where strangers would have gone the wrong way, but they made no mistake.”

In all, the raiders made off with $208,000, about $3.2 million in today’s dollars. They were apprehended, but the Canadian authorities refused to extradite them, and their leader, Bennett Young, traveled in Europe until it was safe to return to Kentucky after the war. His exploit became the northernmost land action in the Civil War.

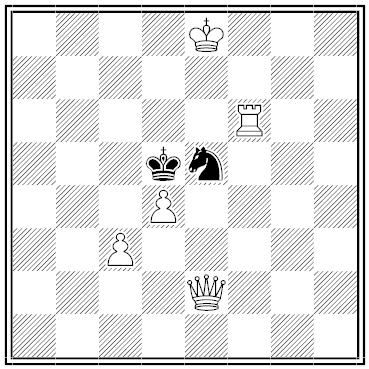

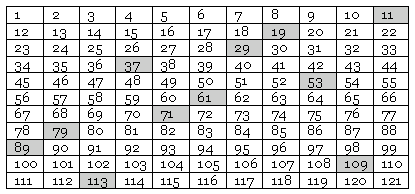

Transversal of Primes

Choose a prime number p, draw a p×p array, and fill it with integers like so:

Now: Can we always find p cells that contain prime numbers such that no two occupy the same row or column? (This is somewhat like arranging rooks on a chessboard so that every rank and file is occupied but no rook attacks another.)

The example above shows one solution for p=11. Does a solution exist for every prime number? No one knows.

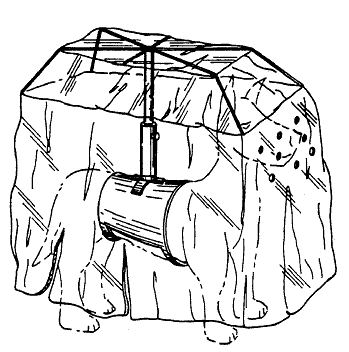

Dog Umbrella

Patented in 1992 by Celess Antoine. Some things don’t need a lot of explaining.

If you live in an arid climate there’s an alternate solution.

Breakup Music

Erik Satie’s 1893 composition Vexations bears an inscrutable inscription: “In order to play the theme 840 times in succession, it would be advisable to prepare oneself beforehand, and in the deepest silence, by serious immobilities.” This seems to mean that the piece should be repeated 840 times in performance, which would take 12-24 hours, depending on how you interpret the tempo marking “Très lent.”

“It is perhaps not surprising that few of the performances [Gavin] Bryars lists have been complete,” writes Robert Orledge in Satie the Composer, “for with the bass theme repeated between each 13-beat harmonization, it recurs 3,360 times.”

“It is probable that Satie’s vexations are those expressed in the latter part of his difficult relationship with Suzanne Valadon, that is to say, somewhere between April and early June 1893.”

“A Tradesman in a Difficulty”

A puzzle by Angelo Lewis, writing as “Professor Hoffman” in 1893:

A man went into a shop in New York and purchased goods to the amount of 34 cents. When he came to pay, he found that he had only a dollar, a three-cent piece, and a two-cent piece. The tradesman had only a half- and a quarter-dollar. A third man, who chanced to be in the shop, was asked if he could assist, but he proved to have only two dimes, a five-cent piece, a two-cent piece, and a one-cent piece. With this assistance, however, the shopkeeper managed to give change. How did he do it?

Moving Target

What is the smallest integer that’s not named on this blog?

Suppose that the smallest integer that’s not named (explicitly or by reference) elsewhere on the blog is 257. But now the phrase above refers to that number. And that instantly means that it doesn’t refer to 257, but presumably to 258.

But if it refers to 258 then actually it refers to 257 again. “If it ‘names’ 257 it doesn’t, so it doesn’t,” writes J.L. Mackie, “but if it doesn’t, then it does, so it does.”

(Adduced by Max Black of Cornell.)

Unquote

“Men do not desire merely to be rich, but to be richer than other men.” — John Stuart Mill

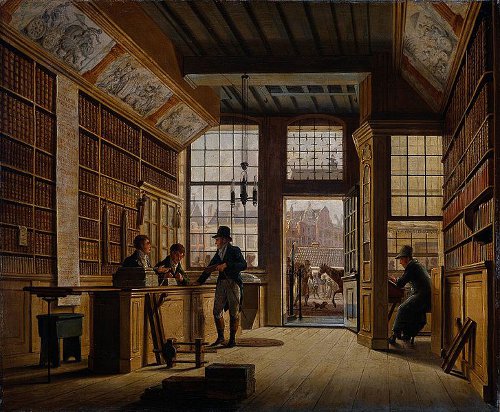

Shop Talk

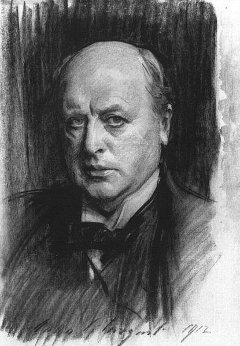

“I’m glad you like adverbs,” wrote Henry James to a correspondent. “I adore them; they are the only qualifications I really much respect, and I agree with the fine author of your quotations in saying — or in thinking — that the sense for them is the literary sense. None other is much worth speaking of.”

As Somerset Maugham prepared to write Of Human Bondage, “I began with the impossible aim of using no adjectives at all. I thought that if you could find the exact term a qualifying epithet could be dispensed with. As I saw it in my mind’s eye my book would have the appearance of an immensely long telegram in which for economy’s sake you had left out every word that was not necessary to make the sense clear. I have not read it since I corrected the proofs and do not know how near I came to doing what I tried. My impression is that it is written at least more naturally than anything I had written before.”

Edgar Allan Poe bewailed the passing of the dash. “The Byronic poets were all dash,” he complained. “The dash gives the reader a choice between two, or among three or more expressions, one of which may be more forcible than another, but all of which help out the idea. It stands, in general, for these words — ‘or, to make my meaning more distinct’. This force it has — and this force no other point can have; since all other points have well-understood uses quite different from this. Therefore, the dash cannot be dispensed with.”

When a Boston girl took Mark Twain to task for splitting infinitives, he confessed that “I have certain instincts, and I wholly lack certain others. (Is that ‘wholly’ in the right place?) For instance, I am dead to adverbs; they cannot excite me. To misplace an adverb is a thing which I am able to do with frozen indifference; it can never give me a pang. … I know thoroughly well that I shall never be able to get it into my head. Mind, I do not say I shall not be able to make it stay there; I say and mean that I am not capable of getting it into my head. There are subtleties which I cannot master at all, — they confuse me, they mean absolutely nothing to me, — and this adverb plague is one of them.”