Three pirates find themselves on an island with a chest full of miscellaneous treasure. They have no weighing or measuring equipment. How can they divide the loot to the satisfaction of each?

Three pirates find themselves on an island with a chest full of miscellaneous treasure. They have no weighing or measuring equipment. How can they divide the loot to the satisfaction of each?

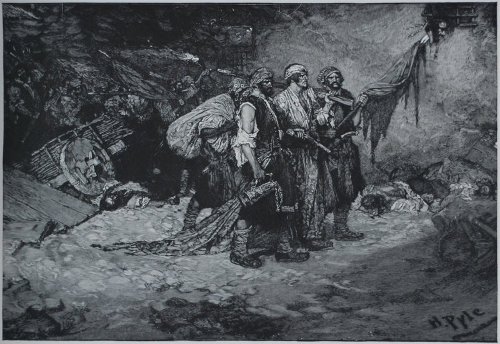

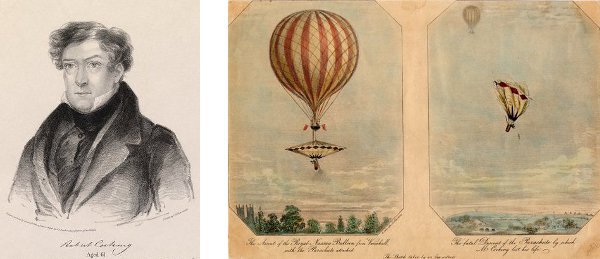

The following is an account of the post-mortem examination of the body of Mr. Robert Cocking, aged sixty-one, who fell with a suicidal machine called a parachute, from the cord of a balloon which ascended from Vauxhall Gardens, on the 24th of July, 1837. The height which the balloon had reached when the parachute commenced its descent, is stated to have been 5000 feet. The instrument of death was simply a canvas toy, constructed in ignorance, and used with the hardihood which might distinguish an unfortunate being who contemplated his own destruction by extraordinary and wonder-exciting means,– an end which, without the motive, was more effectually attained, by the crushing of the parachute in the air as it dropped:–

On the right side.–The second, third, fourth, and fifth ribs broken near their junction, with their cartilages. The second, fourth, fifth, and sixth broken also near their junction with the vertebrae. The second, fourth, fifth, and sixth ribs also broken at their greatest convexity.

On the left side.–The second, third, fourth, and sixth ribs broken near their cartilages, and also near their angles.

The clavicle on the right side fractured at the junction of the external with the middle third.

The second lumbar vertebra fractured through its body; the transverse processes of several of the lumbar vertebrae broken.

Comminuted fracture and separation of the bones of the pelvis at the sacro-iliac symphyses.

The ossa nasi fractured.

The right ankle dislocated inwards; the astragalus and os calcis fractured.

The viscera of the head, chest, and abdomen free from any morbid appearances.F.C. Finch, G. Macilwain, W. Maugham, T. Greenwood, W. Thompson, surgeons

— Lancet, Aug. 5, 1837

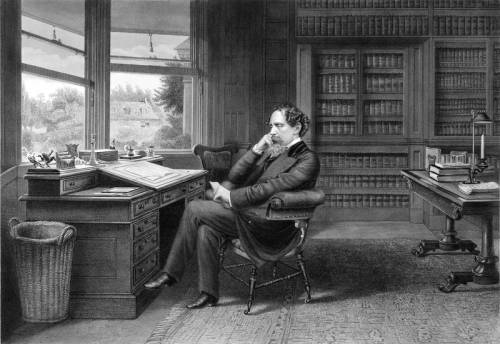

In June 1857, Hans Christian Andersen arrived at Charles Dickens’ new country home, Gads Hill Place. Andersen was an enormous admirer of Dickens — he had just dedicated a novel to him and was eager to enjoy a fortnight with his “friend and brother.”

Enjoy it he did. He gathered nosegays in the woods, cut figures from paper, invited Dickens’ son Charley to shave him, and explored London in cabs while hiding his valuables in his boots. He found that Dickens had an excellent supply of dinner whiskey and could offer a large tumbler of gin and sherry afterward. He watched Dickens perform in The Frozen Deep, burst into tears at the death scene, drank champagne with the cast, and returned to see it again a week later.

So delighted was he that in the end he stayed five weeks instead of the planned two. “None of your friends can be more closely attached to you than I,” he wrote on the way back to Denmark. “The visit to England, the stay with you, is a bright point in my life. … I understood every minute that you cared for me, that you were glad to see me, and were my friend.”

When Dickens returned to the house, he stole into Anderson’s bedroom and affixed a card to the dressing-table mirror. “Hans Christian Andersen slept in this room for five weeks,” it said, “which seemed to the family AGES.”

A senior relief official during the Irish potato famine was named Edward Pine Coffin.

“Supposing some unfortunate lady was confined with twins and one child was born 10 minutes before 1 o’clock; if the clock was put back, the registration of the time of birth of the two children would be reversed. … Such an alteration might conceivably affect the property and titles in that house.” — Lord Balfour of Burleigh, opposing daylight saving time, House of Lords, May 1916

During an Air Force training mission over Montana on Feb. 2, 1970, Gary Foust’s F-106 entered an uncontrollable flat spin at 35,000 feet.

He rode it down to 12,000 feet, ejected — and watched as the plane righted itself, descended into a snowy field, and made a gentle belly landing. Its engine was still running when the police arrived.

After repairs, the fighter was returned to service in California and New York. Today it’s on display in a museum at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio.

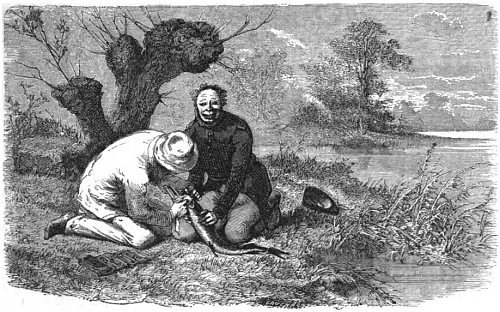

When I lived at Durham, I was walking one evening in a park belonging to the Earl of Stamford, along the bank of a lake where fishes abounded. My attention was turned towards a fine jack of about 6 lbs., which, seeing me, darted into the middle of the water. In its flight it struck its head against the stump of a post, fractured its skull, and wounded a part of the optic nerve. The animal gave signs of ungovernable pain, plunged to the bottom of the water, burying its head in the mud, and turning with such rapidity that I lost it for a moment; then it returned to the top, and threw itself clean out of the water on to the bank. I examined the fish, and found that a small part of the brain had gone out through the fracture of the cranium.

I carefully replaced the shattered brain, and, with a small silver tooth-pick, raised the depressed parts of the skull. The fish was very quiet during the operation; then I replaced it in the pond. It seemed at first relieved, but after some minutes it threw itself about, plunged here and there, and at last threw itself once more out of the water. It continued thus to act many times following. I called the keeper, and, with his assistance, applied a bandage to the fracture. This done, we threw the fish into the water, and left him to his fate. The next morning, when I appeared on the bank, the pike came to me near where I sat, and put his head near my feet! I thought the act extraordinary, but taking up the fish, without any resistance on its part, I examined the head, and found that it was going on well. I then walked along the banks for some time; the fish did not cease to swim after me, turning when I turned; but as it was blind on the side where it was wounded, it appeared always agitated when the injured eye was turned toward the bank. On this, I changed the direction of my movements. The next day I brought some young friends to see this fish, and the pike swam towards me as before. Little by little he became so tame that he came when I whistled, and ate from my hand. With other people, on the contrary, it was as gloomy and fierce as it always had been.

— “Dr. Warwick,” anecdote read before the Literary and Philosophical Society of Liverpool, 1850, quoted in Ernest Menault, The Intelligence of Animals, 1869

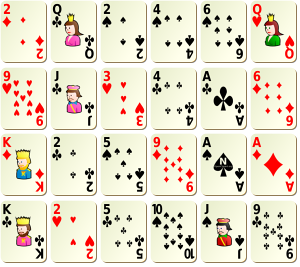

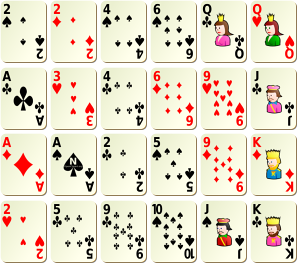

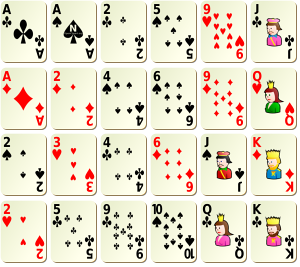

From Ross Honsberger via Martin Gardner: Deal cards into any rectangular array:

Put each row into numerical order:

Now put each column into numerical order:

Surprisingly, that last step hasn’t disturbed the preceding one — the rows are still in order. Why?

nepotal

adj. relating to a nephew

“That is my nephew,” said a man to his sister.

“He is not my nephew,” she said.

How is this possible?