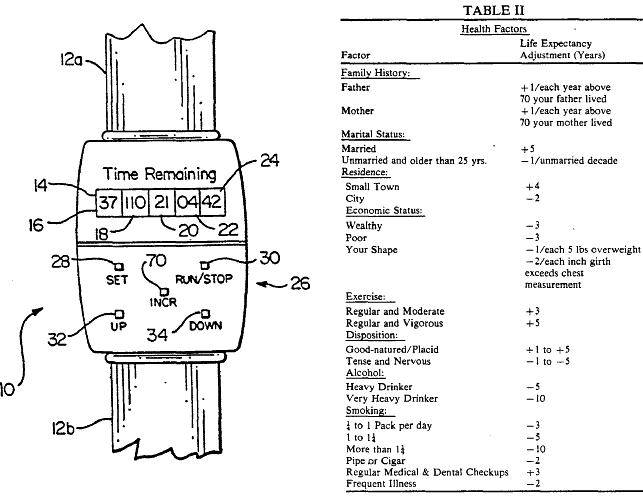

David Kendrick’s “life expectancy timepiece,” patented in 1991, offers a running countdown of your remaining time on earth.

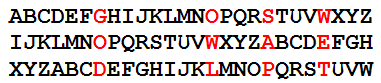

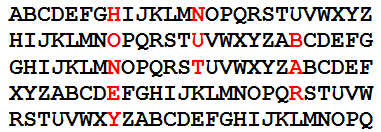

Using actuarial data, enter the years, days, hours, minutes, and seconds that you expect to live, and adjust this total according to the health factors in Table II.

Then set it going. It’s not quite as bad as it looks: You can press the RUN/STOP button to pause the countdown while you’re engaged in a healthful activity (“e.g. taking a walk, breathing fresh air, etc.”). And life expectancy improves with age, so you can add a few years on certain birthdays.

But still, it’s pretty sobering. An alternate version actually includes a speaker that provides “an audible signal, as a reminder that time is passing.” “This audible signal may be adapted to operate automatically at a particular time each day or may be suppressed by the user.”