Asking Back

On the morning after a battle, Mary prays that her husband has not been killed. Is this a coherent plea? It would seem that the matter has already been decided: Her husband is either alive or dead. If he is dead, then in order to grant Mary’s prayer God would have to change the past retroactively.

“If one does not think of [such a] case, the idea of doing something in order that something else should previously have happened may seem sheer raving insanity,” writes Michael Dummett. “But suppose I hear on the radio that a ship has gone down in the Atlantic two hours previously, and that there were few survivors: my son was on that ship, and I at once utter a prayer that he should have been among the survivors, that he should not have drowned; this is the most natural thing in the world.”

Perhaps God can grant Mary’s prayer without changing the past: Perhaps, using divine foreknowledge, he interceded at the time of the battle knowing that she would later pray for this. “One of the things taken into account in deciding [the outcome], and therefore one of the things that really causes it to happen, may be this very prayer that we are now offering,” writes C.S. Lewis.

But this entails an oddity of its own — such favors, it seems, are available only to those who are in some doubt about a past event. God will intercede today for a prayer tomorrow — but only an uncertain person would make such a prayer. “I may pray that the announcer has made a mistake in not including my son’s name on the list of survivors,” Dummett writes, “but once I am convinced that no mistake has been made, I will not go on praying for him to have survived. I should regard this kind of prayer as something to which it was possible to have recourse only when an ordinary doubt about what had happened could be entertained.”

(Michael Dummett, “Bringing about the Past,” Philosophical Review, July 1964.)

Multiplication by Transplant

Limerick

A sleeper from the Amazon

Put nighties of his gramazon.

The reason? That

He was too fat

To get his own pajamazon.

— Anonymous

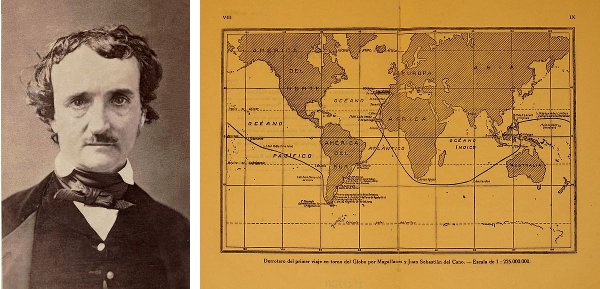

“Three Sundays in a Week”

In 1841 Edgar Allan Poe pointed out the confusion that can result when a ship reckons time while circling the world. Captain Smitherton and Captain Pratt have just returned from circumnavigating the globe, one traveling eastward and the other westward, while Kate and her father Mr. Rumgudgeon have remained in London. On reuniting, they discover some confusion: Captain Pratt thinks that tomorrow will be Sunday, Smitherton thinks that yesterday was Sunday, and Kate and Rumgudgeon think that today is Sunday. Finally Smitherton says:

What fools we two are ! — Mr. Rumgudgeon, the matter stands thus: The earth, you know, is, in round numbers, twenty-four thousand miles in circumference. Now the earth turns on its own axis, spins round, these twenty-four thousand miles, going from west to east, in precisely twenty-four hours. Well, sir, that is at the rate of one thousand miles an hour.

Now suppose that I sail from this position a thousand miles east. Of course, I anticipate the rising of the sun here at London by just one hour. I see the sun rise one hour before you do. Proceeding in the same direction yet another thousand miles, I anticipate the rising by two hours; another thousand, and I anticipate it by three hours: and so on, until I go entirely round the globe, and back to this spot, when having gone twenty-four thousand miles east, I anticipate the rising of the London sun by no less than twenty-four hours; that is to say, I am a day in advance of your time. Understand?

But Captain Pratt, when he had sailed a thousand miles west of this position, was an hour, and when he had sailed twenty-four thousand miles was twenty-four hours, or one day, behind the time at London. Thus, with me, yesterday was Sunday; thus, with you, to-day is Sunday; and thus, with Captain Pratt, to-morrow will be Sunday. And what is more, Mr. Rumgudgeon, it is positively clear that we are all right.

Mr. Rumgudgeon, who had forbidden Kate to marry until there were “three Sundays in a week,” now relents. Too bad for him — the international date line would shortly obviate the problem.

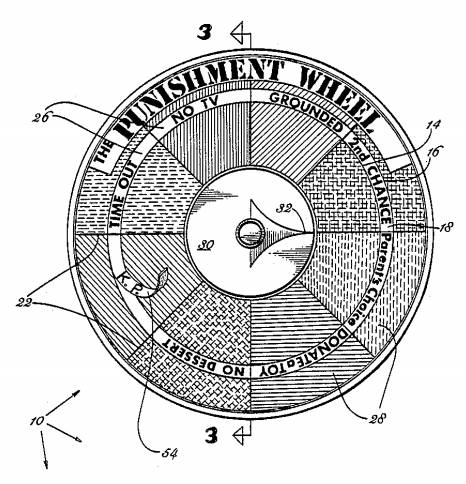

Doom Roulette

With Jose Gonzalez’ “punishment wheel,” patented in 1989, a misbehaving child can randomly choose the punishment he’ll receive. “From the child’s point of view, it appears that an inanimate object is choosing and imposing the punishment, instead of his parents. Direct parent-child conflict is thereby eliminated.”

Available punishments, provided on decals, include NO TV, TIME OUT, GROUNDED, 2ND CHANCE, NO DESSERT, DONATE A TOY, PARENT’S CHOICE, K.P., NO ALLOWANCE, NO SPORTS, NO PHONE, NO FRIENDS, KID’S CHOICE, SWATS [a spanking], NO VISITING, NO TREAT, and HOUSE CHORES. But “the punishments need not be those shown in Fig. 4, but could be any set of punishments, expressed in any language, deemed suitable for the disciplinary style of particular parents and degree of maturity of their child.”

Pride of Place

If we made a dictionary of all the integers, arranging their English names in alphabetical order, which would come first and which last?

Pro Tips

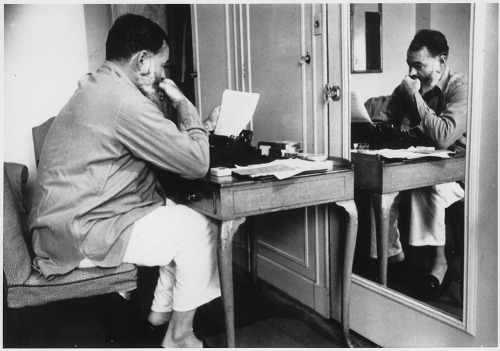

“Dancing is a sweat job. … When you’re experimenting you have to try so many things before you choose what you want, that you may go days getting nothing but exhaustion. This search for what you want is like tracking something that doesn’t want to be tracked. It takes time to get a dance right, to create something memorable. There must be a certain amount of polish to it. I don’t want it to look anything but accomplished, and if I can’t make it look that way, then I’m not ready yet. I always try to get to know my routine so well that I don’t have to think, ‘What comes next?’ Everything should fall right into line, and then I know I’ve got control of the bloody floor.” — Fred Astaire

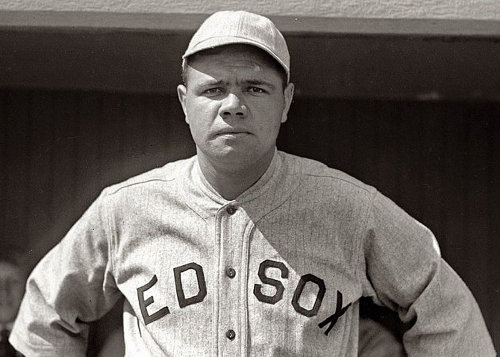

“How to hit home runs: I swing as hard as I can, and I try to swing right through the ball. In boxing, your fist usually stops when you hit a man, but it’s possible to hit so hard that your fist doesn’t stop. I try to follow through in the same way. The harder you grip the bat, the more you can swing it through the ball, and the farther the ball will go. I swing big, with everything I’ve got. I hit big or I miss big. I like to live as big as I can.” — Babe Ruth

“Don’t get discouraged because there’s a lot of mechanical work to writing. … I rewrote the first part of A Farewell to Arms at least fifty times. … The first draft of anything is shit. When you first start to write you get all the kick and the reader gets none, but after you learn to work it’s your object to convey everything to the reader so that he remembers it not as a story he has read but something that has happened to himself. That’s the true test of writing.” — Ernest Hemingway

A-Roving

“The Spirit of Byron,” a popular English print, circa 1830.

A footnote in Byron’s Don Juan mentions a rhyming contest between John Sylvester and Ben Jonson:

“I, John Sylvester, lay with your sister.”

“I, Ben Jonson, lay with your wife.”

“That is not rhyme.”

“No, but it is true.”

Unquote

“Whoever in discussion adduces authority uses not intellect but rather memory.” — Leonardo