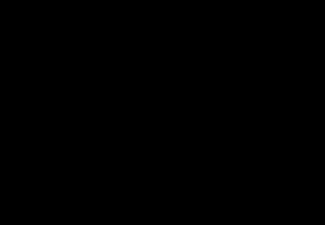

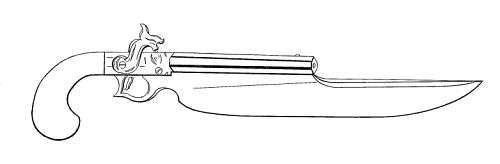

George Elgin’s “pistol sword,” patented in 1837, combines romance and efficiency:

The nature of my invention consists in combining the pistol and Bowie knife, or the pistol and cutlass, in such manner that it can be used with as much ease and facility as either the pistol, knife, or cutlass could be if separate, and in an engagement, when the pistol is discharged, the knife (or cutlass) can be brought into immediate use without changing or drawing, as the two instruments are in the hand at the same time.

This is one of the earliest U.S. patents — number 254.

Related: A gruesome piece of battlefield medicine from the Napoleonic campaigns of 1806 — a soldier’s face was transfixed by a bayonet that projected five inches from his right temple:

The man was knocked down, but did not lose his senses. He made several ineffectual efforts to pull the bayonet out, and two comrades, one holding the head, whilst the other dragged at the weapon, also failed. The poor wounded man came to me leaning on the arms of two fellow-soldiers. I endeavored, with the assistance of a soldier to pull out the bayonet, but it seemed to me as if fixed in a wall. The soldier who helped me desired the patient to lie down on his side, and putting his foot on the man’s head, with both hands he dragged out the bayonet, which was immediately followed by considerable hemorrhage, the blood pouring forth violently and abundantly. The patient then first felt ill, and, as I thought he would die, I left him to dress other wounded. After twenty minutes he revived, and said he was much better, and I then dressed him. We were in the snow, and as he was very cold the whole of his head was well wrapped up in charpie and bandages. He set off to Warsaw with another soldier; went partly on foot, partly on horseback, or in a cart, from barn to barn, and often from wood to wood, and reached Warsaw in six days. Three months after, I saw him in the hospital, perfectly recovered. He had lost his sight on the right side; the eye and lid had, however, preserved their form and mobility, but the iris remained much dilated and immovable.

From Paul Fitzsimmons Eve, A Collection of Remarkable Cases in Surgery, 1857.