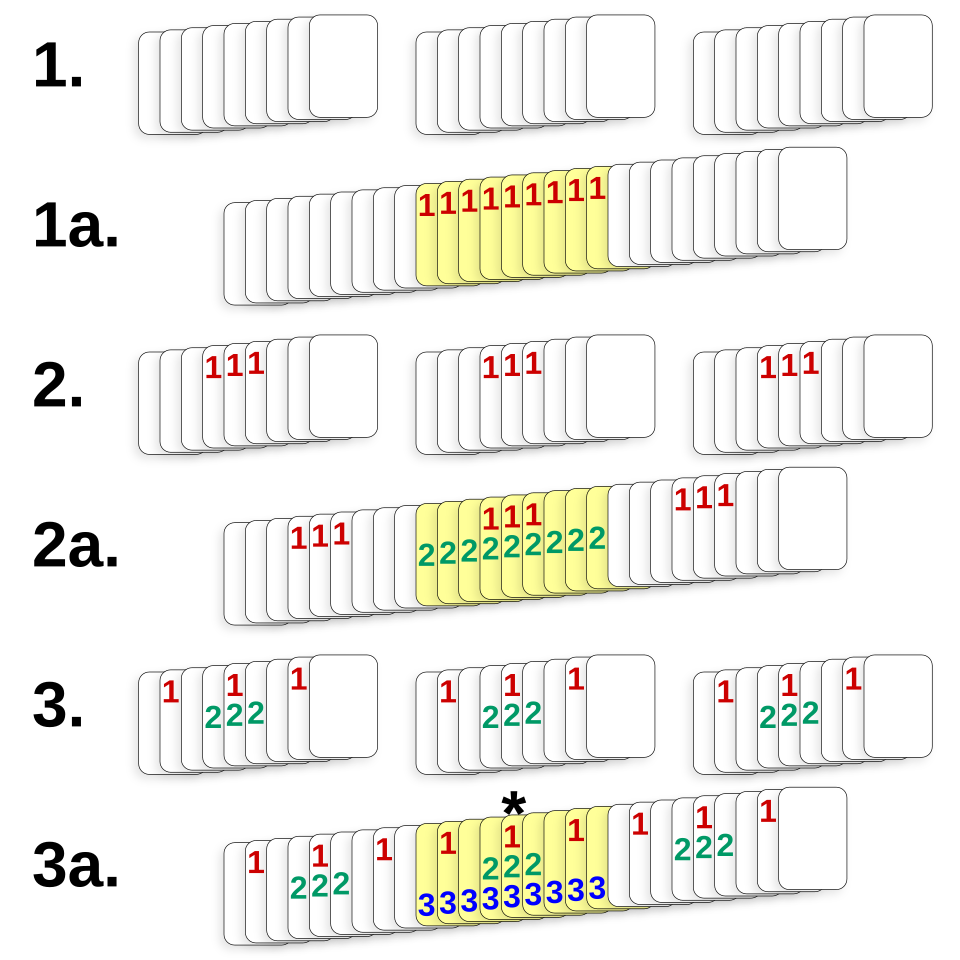

Edmund Conti notes an unfortunate mannerism in Ngaio Marsh’s 1970 detective novel When in Rome:

Page 14: “Here,” he said in basic Italian. “Keep the change.” The waiter ejaculated with evident pleasure.

Page 49: “Nothing to what I was!” Sophy ejaculated.

Page 74: They could be heard ejaculating in some distant region.

Page 75: “Ah,” ejaculated Grant, “don’t remind me of that for God’s sake!”

Page 84: “Violetta, is it!” he ejaculated.

Page 87: “Good God!” the Major ejaculated.

Page 88: “Well!” the Major ejaculated.

Page 88: There were more ejaculations and much talk of coincidence …

Page 104: Marco gave an ejaculation and a very slight wince.

Page 109: “Phew!” said the Major, who seemed to be stuck with this ejaculation.

Page 140: “Eccellenza!” the Questore ejaculated.

Page 145: The Van der Veghels broke into scandalized ejaculations, first in their language and then in English.

Page 149: Sophy had given a little ejaculation.

Page 149: “I remember!” the Baron ejaculated.

Page 157: Finally Giovanni gave a sharp ejaculation.

Page 188: “We would exclaim, gaze at each at each other, gabble, ejaculate, tell each other how we felt …”

Page 194: Bergami ejaculated and answered so rapidly that Alleyn could only just make out what he said.

Conti adds, “Cigarette?”