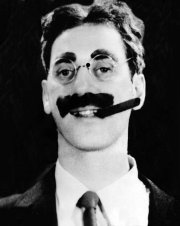

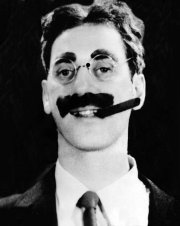

Letter from Groucho Marx to the Franklin Corporation, April 24, 1961:

Dear Mr. Goodman:

I received the first annual report of the Franklin Corporation and though I am not an expert at reading balance sheets, my financial advisor (who, I assure you, knows nothing) nodded his head in satisfaction.

You wrote that you hope I am not one of those borscht circuit stockholders who get a few points’ profit and hastily scram for the hills. For your information, I bought Alleghany Preferred eleven years ago and am just now disposing of it.

As a brand new member of your family, strategically you made a ghastly mistake in sending me individual pictures of the Board of Directors. Mr. Roth, Chairman of the Board, merely looks sinister. You, the President, look like a hard worker with not too much on the ball. No one named Prosswimmer can possibly be a success. As for Samuel A. Goldblith, PhD., head of Food Technology at MIT, he looks as though he had eaten too much of the wrong kind of fodder.

At this point I would like to stop and ask you a question about Marion Harper Jr. To begin with, I immediately distrust any man who has the same name as his mother. But the thing that most disturbs me about Junior is that I don’t know what the hell he’s laughing at. Is it because he sucked me into this Corporation? This is not the kind of face that inspires confidence in a nervous and jittery stockholder.

George S. Sperti, I dismiss instantly. Any man who is the President of an outfit called Institutum Divi Thomae will certainly bear watching. Is he trying to impress stockholders with his knowledge of Latin? If so, why doesn’t he read, ‘Winnie ille Pu’? James J. Sullivan, I am convinced, is Paul E. Prosswimmer photographed from a different angle.

Offhand, I would say that I have summed up your group fairly accurately. I hope, for my sake, that I am mistaken.

In closing, I warn you, go easy with my money. I am in an extremely precarious profession whose livelihood depends upon a fickle public.

Sincerely yours,

Groucho Marx

(temporarily at liberty)