A Key Point

Complaint received by a French typewriter shop, reprinted in a local newspaper on the Île de Ré:

Monsixur,

Il y a quxlquxs sxmainxs jx mx suis offxrt unx dx vos machinxs à écrirx. Au début j’xn fus assxz contxnt. Mais pas pour longtxmps. Xn xffxt, vous voyxz vous-mêmx lx défaut. Chaqux fois qux jx vxux tapxr un x, c’xst un x qux j’obtixns. Cxla mx rxnd xnragé. Car quand jx vxux un x, c’xst un x qu’il mx faut xt non un x. Cxla rxndrait n’importx qui furixux. Commxnt fairx pour obtxnir un x chaqux fois qux jx desirx un x? Un x xst un x, xt non un x. Saisissxz-vous cx qux jx vxux dirx?

Jx voudrais savoir si vous êtxs xn mxsurx dx mx livrxr unx machinx à écrirx donnant un x chaqux fois qux j’ai bxsoin d’un x. Parcx qux si vous mx donnxz unx machinx donnant un x lorsqu’on tapx un x, vous pourrxz ravoir cx damné instrumxnt. Un x xst très bixn tant qux x, mais, oh xnfxr!

Sincèrxmxnt à vous, un dx vos clixnts rxndu xnragé.

Xugènx X—-

From John Julius Norwich, Christmas Crackers, 1981.

A Study in Oils

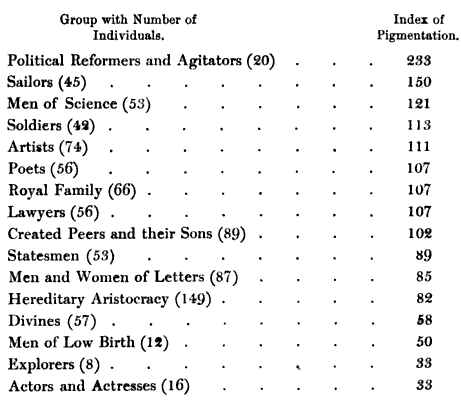

In seeking to understand how a person’s ability might vary with his complexion, Havelock Ellis chose an unusual data set: the National Portrait Gallery. Ellis spent two years examining paintings of notable Britons in various fields and established an “index of pigmentation” in each group by multiplying the number of fair people by 100 and dividing by the number of dark people. Results:

An index greater than 100 means that fair people predominate in the group; one less than 100 means that dark people predominate. The list includes both men and women.

In general, Ellis concluded, the fair man tends to be “bold, energetic, restless, and domineering,” while the dark man is “resigned and religious and imitative, yet highly intelligent.” “While the men of action thus tend to be fair, the men of thought, it seems to me, show some tendency to be dark.”

Ellis speculated that the British aristocracy tended to be dark because peers could choose the most beautiful women, and British women with the greatest reputation for beauty tended to be dark: a group of 15 English women of letters had an index of 100, while 13 famous beauties rated 44.

(“The Comparative Abilities of the Fair and the Dark,” Monthly Review, August 1901.)

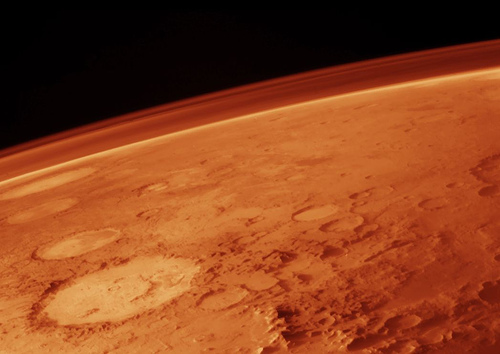

Long Distance

Suppose I pour poison in the water tank of a space ship while it stands on earth. My purpose is to kill the space traveller, and I succeed: when he reaches Mars he takes a drink and dies. Two events are easy to distinguish: my pouring of the poison, and the death of the traveller. One precedes the other, and causes it. But where does the event of my killing the traveller come in? The most usual answer is that my killing the traveller is identical with my pouring the poison. In that case, the killing is over when the pouring is. We are driven to the conclusion that I have killed the traveller long before he dies.

— Donald Davidson, “The Individuation of Events,” in N. Rescher et al., eds., Essays in Honor of Carl G. Hempel, 1969

More Amusing Indexes

From Oliver Wendell Holmes’ The Poet at the Breakfast-Table, 1872:

Act to make the poor rich by making the rich poorer, 3

Ankle, wonderful effects of breaking a bone in the, 114

Batrachian reservoir (frog-pond in vulgar speech), the palladium of our city, 369

Biography, penalties of being its subject, 191 et seq.

Common virtues of humanity not to be confiscated to the use of any one creed, 360

House-flies mysterious creatures, 288

Ideas often improve by transplantation, 171

Intellects, one story, two story, three story, 50

Jests distress some people, 289

Justice, an algebraic x, 317

Life a fatal complaint, and contagious, 395

Limitations, human, not to be transferred to the Infinite, 319

Millionaires cannot be exterminated, 5

Non-clerical minds, hopeful for the future of the race, 302

Old people almost wish to lose their blessings for the pleasure of remembering them, 385

Poem, is it hard work to write one?, 111

Power, we have no respect for as such, 317

Private property in thought hard to get and keep, 356

Ribbon in button-hole pleases the author, 322

Rigorists, mellowing, better than tightening liberals, 19

Tattooing with the belief of our tribe while we are in our cradles, 384

Traditionalists eliminate cause and effect from the domain of morals, 265

And from Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy, 1621:

Atheists described, 705

Baseness of birth no disparagement, 509

Beer censured, 145

Black eyes best, 519

Blow on the head cause of melancholy, 247

Confidence in his physician half a cure, 392

Crocodiles jealous, 629

Eunuchs why kept, and where, 642

Fishes in love, 493

Great men most part dishonest, 636

Guts described, 96

Hell where, 318

How oft ’tis fit to eat in a day, 307

Ignorance the mother of devotion, 678

Man the greatest enemy to man, 84

Old folks apt to be jealous, 632

Poets why poor, 203

Salads censured, 145

Step-mother, her mischiefs, 241

Venison a melancholy meat, 142

Why good men are often rejected, 415

Why fools beget wise children, wise men fools, 139, 140

The New York Times Book Review called Burton’s index “a readerly pleasure in itself.”

See Memorable Indexes.

Self Seeking

Letter from Winston Churchill to American author Winston Churchill, June 1899:

Mr. Winston Churchill presents his compliments to Mr. Winston Churchill, and begs to draw his attention to a matter which concerns them both. He has learnt from the Press notices that Mr. Winston Churchill proposes to bring out another novel, entitled Richard Carvel, which is certain to have a considerable sale both in England and America. Mr. Winston Churchill is also the author of a novel now being published in serial form in Macmillan’s Magazine, and for which he anticipates some sale both in England and America. He also proposes to publish on the 1st of October another military chronicle on the Soudan War. He has no doubt that Mr. Winston Churchill will recognise from this letter — if indeed by no other means — that there is grave danger of his works being mistaken for those of Mr. Winston Churchill. He feels sure that Mr. Winston Churchill desires this as little as he does himself. In future to avoid mistakes as far as possible, Mr. Winston Churchill has decided to sign all published articles, stories, or other works, ‘Winston Spencer Churchill,’ and not ‘Winston Churchill’ as formerly. He trusts that this arrangement will commend itself to Mr. Winston Churchill, and he ventures to suggest, with a view to preventing further confusion which may arise out of this extraordinary coincidence, that both Mr. Winston Churchill and Mr. Winston Churchill should insert a short note in their respective publications explaining to the public which are the works of Mr. Winston Churchill and which those of Mr. Winston Churchill. The text of this note might form a subject for future discussion if Mr. Winston Churchill agrees with Mr. Winston Churchill’s proposition. He takes this occasion of complimenting Mr. Winston Churchill upon the style and success of his works, which are always brought to his notice whether in magazine or book form, and he trusts that Mr. Winston Churchill has derived equal pleasure from any work of his that may have attracted his attention.

In 1959 Bertrand Russell and Lord Russell of Liverpool wrote a joint letter to the Times:

“Sir: In order to discourage confusions which have been constantly occurring, we beg herewith to state that neither of us is the other.”

All Aboard

One hundred people board a 100-seat airplane. The first one has lost his boarding pass, so he sits in a random seat. Each subsequent passenger sits in his own seat if it’s available or takes a random unoccupied seat if it’s not.

What’s the probability that the 100th passenger finds his seat occupied?

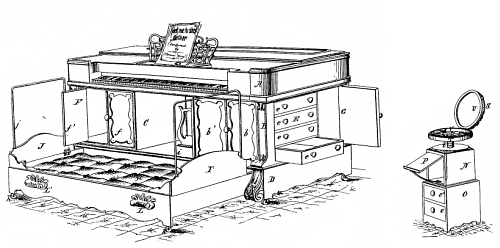

Swiss Army Piano

Charles Hess patented this combination piano, couch, and bureau in 1866, intending it for hotels and boarding schools in which some bedrooms are used as parlors during daylight hours. Closet F holds the bedclothes, and closet G holds a washbowl, pitcher, and towels.

“It has been found by actual use that this addition to a piano-forte does not in the least impair its qualities as a musical instrument, but, on the contrary, adds considerably to its reverberatory power.”

Charmingly, the stool doubles as a writing desk (P), its seat conceals a looking glass (U), and its body serves as a lady’s work box, complete with a cushion for holding pins and needles.

Complaint

Sir,

A little light might be shed, with advantage, upon the high-handed methods of the Passport Department at the Foreign Office. On the form provided for the purpose, I described my face as ‘intelligent’. Instead of finding this characterization entered, I have received a passport on which some official utterly unknown to me has taken it upon himself to call my face ‘oval’.

Yours very truly,

Bassett Digby

— Letter to the Times, February 17, 1915

First Place

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

“My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

That’s “Ozymandias,” Shelley’s most popular sonnet. The world was actually offered two entries on this theme: Shelley was writing in competition with his friend Horace Smith, whose own poem appeared in The Examiner three weeks later. Here’s his try:

In Egypt’s sandy silence, all alone,

Stands a gigantic Leg, which far off throws

The only shadow that the Desert knows:–

“I am great OZYMANDIAS,” saith the stone,

“The King of Kings; this mighty City shows

“The wonders of my hand.”– The City’s gone,–

Nought but the Leg remaining to disclose

The site of this forgotten Babylon.

We wonder,–and some Hunter may express

Wonder like ours, when thro’ the wilderness

Where London stood, holding the Wolf in chace,

He meets some fragment huge, and stops to guess

What powerful but unrecorded race

Once dwelt in that annihilated place.

Enchantingly, Smith titled this “On A Stupendous Leg of Granite, Discovered Standing by Itself in the Deserts of Egypt, with the Inscription Inserted Below.” You can decide which deserves immortality.