charrette

n. a final, intensive effort to finish a project before a deadline

“To My Old Master”

In August 1865, Col. P.H. Anderson of Big Spring, Tenn., wrote to his former slave Jourdon Anderson, now emancipated in Ohio, and asked him to return to work on his farm. Anderson dictated this letter in response:

Sir: I got your letter, and was glad to find that you had not forgotten Jourdon, and that you wanted me to come back and live with you again, promising to do better for me than anybody else can. I have often felt uneasy about you. I thought the Yankees would have hung you long before this, for harboring Rebs they found at your house. I suppose they never heard about your going to Colonel Martin’s to kill the Union soldier that was left by his company in their stable. Although you shot at me twice before I left you, I did not want to hear of your being hurt, and am glad you are still living. It would do me good to go back to the dear old home again, and see Miss Mary and Miss Martha and Allen, Esther, Green, and Lee. Give my love to them all, and tell them I hope we will meet in the better world, if not in this. I would have gone back to see you all when I was working in the Nashville Hospital, but one of the neighbors told me that Henry intended to shoot me if he ever got a chance.

I want to know particularly what the good chance is you propose to give me. I am doing tolerably well here. I get twenty-five dollars a month, with victuals and clothing; have a comfortable home for Mandy, — the folks call her Mrs. Anderson, — and the children — Milly, Jane, and Grundy — go to school and are learning well. The teacher says Grundy has a head for a preacher. They go to Sunday school, and Mandy and me attend church regularly. We are kindly treated. Sometimes we overhear others saying, ‘Them colored people were slaves’ down in Tennessee. The children feel hurt when they hear such remarks; but I tell them it was no disgrace in Tennessee to belong to Colonel Anderson. Many darkeys would have been proud, as I used to be, to call you master. Now if you will write and say what wages you will give me, I will be better able to decide whether it would be to my advantage to move back again.

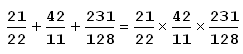

As to my freedom, which you say I can have, there is nothing to be gained on that score, as I got my free papers in 1864 from the Provost-Marshal-General of the Department of Nashville. Mandy says she would be afraid to go back without some proof that you were disposed to treat us justly and kindly; and we have concluded to test your sincerity by asking you to send us our wages for the time we served you. This will make us forget and forgive old scores, and rely on your justice and friendship in the future. I served you faithfully for thirty-two years, and Mandy twenty years. At twenty-five dollars a month for me, and two dollars a week for Mandy, our earnings would amount to eleven thousand six hundred and eighty dollars. Add to this the interest for the time our wages have been kept back, and deduct what you paid for our clothing, and three doctor’s visits to me, and pulling a tooth for Mandy, and the balance will show what we are in justice entitled to. Please send the money by Adams’s Express, in care of V. Winters, Esq., Dayton, Ohio. If you fail to pay us for faithful labors in the past, we can have little faith in your promises in the future. We trust the good Maker has opened your eyes to the wrongs which you and your fathers have done to me and my fathers, in making us toil for you for generations without recompense. Here I draw my wages every Saturday night; but in Tennessee there was never any pay-day for the negroes any more than for the horses and cows. Surely there will be a day of reckoning for those who defraud the laborer of his hire.

In answering this letter, please state if there would be any safety for my Milly and Jane, who are now grown up, and both good-looking girls. You know how it was with poor Matilda and Catherine. I would rather stay here and starve — and die, if it come to that — than have my girls brought to shame by the violence and wickedness of their young masters. You will also please state if there has been any schools opened for the colored children in your neighborhood. The great desire of my life now is to give my children an education, and have them form virtuous habits.

Say howdy to George Carter, and thank him for taking the pistol from you when you were shooting at me.

From your old servant,

Jourdon Anderson.

(Thanks, Simon.)

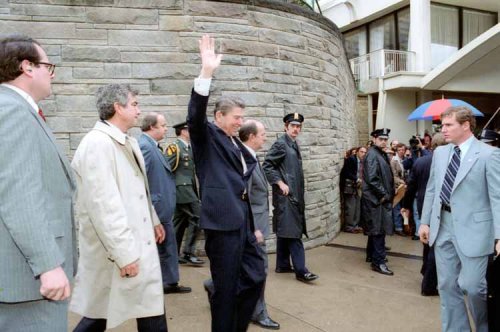

Next in Line

That’s Ronald Reagan, just before being shot by John Hinckley outside the Washington Hilton Hotel on March 30, 1981. The man in the white raincoat is Secret Service agent Jerry Parr; after the shooting, it was Parr who pushed Reagan into a limousine, noticed he was bleeding, and directed the driver to take them to a hospital, probably saving Reagan’s life.

Parr had been inspired to pursue his career by the 1939 film The Code of the Secret Service, in which dashing agent “Brass” Bancroft survives a shooting in Mexico. Bancroft was played by a 28-year-old Ronald Reagan.

(Thanks, Colin.)

Math Notes

A Social Invention

Thomas Edison popularized the word hello. Working in AT&T’s Manhattan archives in 1987, Brooklyn College classics professor Allen Koenigsberg unearthed a letter that Edison had written in August 1877 to the president of a telegraph company that was planning to introduce the telephone in Pittsburgh. Edison wrote:

Friend David, I don’t think we shall need a call bell as Hello! can be heard 10 to 20 feet away. What do you think? EDISON

At the time it was thought that the line would remain open permanently, so a caller needed a way to get the other party’s attention. Apparently hello was a variation on the traditional hound call “Halloo!”

What should the answerer reply? Alexander Graham Bell pressed for Hoy! Hoy!, but Edison equipped the first exchanges, so hello gained the ascendancy there too.

That’s all it took — by 1880 the word was everywhere. “The phone overnight cut right through the 19th-century etiquette that you don’t speak to anyone unless you’ve been introduced,” Koenigsberg told the New York Times. “If you think about it, why didn’t Stanley say hello to Livingston? The word didn’t exist.”

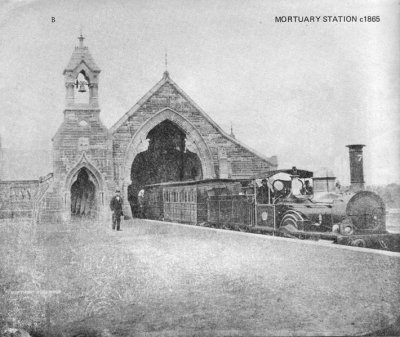

Last Stop

For about half a century, Sydney residents could take a train to the cemetery. It departed twice daily from central Sydney, picking up mourners and coffins along the way, and carried them to the 250-acre Necropolis at Haslem’s Creek.

London’s Necropolis Railway ran at about the same time, carrying cadavers and mourners 23 miles southwest of town to Brookwood, Surrey. In 1904, Railway Magazine called the Brookwood station “the most peaceful in three corners of the kingdom — this station of the dead. Here, even the quiet, subdued puffing of the engine seems almost sympathetic with the sorrow of its living freight.” Both lines closed in the 1940s.

No Thanks

In June 1744, the College of William & Mary invited the Indians of the Six Nations to send six young men to be “properly” educated. They received this reply:

We know that you highly esteem the kind of learning taught in those Colleges, and that the Maintenance of our young Men, while with you, would be very expensive to you. We are convinc’d, therefore, that you mean to do us Good by your Proposal; and we thank you heartily. But you, who are wise, must know that different Nations have different Conceptions of Things; and you will therefore not take it amiss if our Ideas of this kind of Education happen not to be the same with yours. We have had some Experience of it: Several of our young People were formerly brought up at the Colleges of the Northern Provinces; they were instructed in all your Sciences; but when they came back to us, they were bad Runners, ignorant of every means of living in the Woods, unable to bear either Cold or Hunger, knew neither how to build a Cabin, take a Deer, or kill an Enemy, spoke our Language imperfectly, were therefore neither fit for Hunters, Warriors, or Counsellors; they were totally good for nothing. We are, however, not the less oblig’d by your kind Offer, tho’ we decline accepting it; and, to show our grateful Sense of it, if the Gentlemen of Virginia will send us a Dozen of their Sons, we will take great Care of their Education, instruct them in all we know, and make Men of them.

Divine Wills

When Scunthorpe solicitor R.A.C. Symes died in 1930, his will specified that “in the event of the Second Coming of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ my Will shall (so far as may be legally permissible) come into operation and take effect as though I were dead.”

When retired London schoolmaster Ernest Digweed died in 1976, he left his whole estate, more than £26,000, in trust for Jesus Christ at the Second Coming. The estate was to be invested for 80 years, and “if during those 80 years the Lord Jesus Christ shall come to a reign on Earth, then the Public Trustee, upon obtaining proof which shall satisfy them of his identity, shall pay to the Lord Jesus Christ all the property which they hold on his behalf.” If Jesus does not appear, then the estate goes to the crown.

See Heaven on Earth.

Brute Force

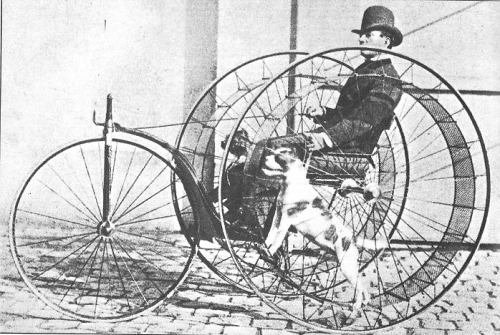

A Paris inventor patented this “cynophere,” or dog-powered velocipede, in 1875.

Twelve years later, a Cleveland designer offered this “motor for street-cars.” That’s progress.