A Social Invention

Thomas Edison popularized the word hello. Working in AT&T’s Manhattan archives in 1987, Brooklyn College classics professor Allen Koenigsberg unearthed a letter that Edison had written in August 1877 to the president of a telegraph company that was planning to introduce the telephone in Pittsburgh. Edison wrote:

Friend David, I don’t think we shall need a call bell as Hello! can be heard 10 to 20 feet away. What do you think? EDISON

At the time it was thought that the line would remain open permanently, so a caller needed a way to get the other party’s attention. Apparently hello was a variation on the traditional hound call “Halloo!”

What should the answerer reply? Alexander Graham Bell pressed for Hoy! Hoy!, but Edison equipped the first exchanges, so hello gained the ascendancy there too.

That’s all it took — by 1880 the word was everywhere. “The phone overnight cut right through the 19th-century etiquette that you don’t speak to anyone unless you’ve been introduced,” Koenigsberg told the New York Times. “If you think about it, why didn’t Stanley say hello to Livingston? The word didn’t exist.”

Last Stop

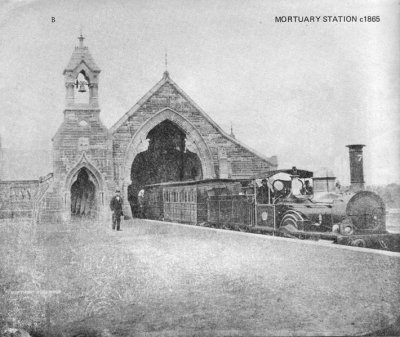

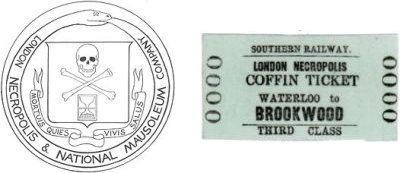

For about half a century, Sydney residents could take a train to the cemetery. It departed twice daily from central Sydney, picking up mourners and coffins along the way, and carried them to the 250-acre Necropolis at Haslem’s Creek.

London’s Necropolis Railway ran at about the same time, carrying cadavers and mourners 23 miles southwest of town to Brookwood, Surrey. In 1904, Railway Magazine called the Brookwood station “the most peaceful in three corners of the kingdom — this station of the dead. Here, even the quiet, subdued puffing of the engine seems almost sympathetic with the sorrow of its living freight.” Both lines closed in the 1940s.

No Thanks

In June 1744, the College of William & Mary invited the Indians of the Six Nations to send six young men to be “properly” educated. They received this reply:

We know that you highly esteem the kind of learning taught in those Colleges, and that the Maintenance of our young Men, while with you, would be very expensive to you. We are convinc’d, therefore, that you mean to do us Good by your Proposal; and we thank you heartily. But you, who are wise, must know that different Nations have different Conceptions of Things; and you will therefore not take it amiss if our Ideas of this kind of Education happen not to be the same with yours. We have had some Experience of it: Several of our young People were formerly brought up at the Colleges of the Northern Provinces; they were instructed in all your Sciences; but when they came back to us, they were bad Runners, ignorant of every means of living in the Woods, unable to bear either Cold or Hunger, knew neither how to build a Cabin, take a Deer, or kill an Enemy, spoke our Language imperfectly, were therefore neither fit for Hunters, Warriors, or Counsellors; they were totally good for nothing. We are, however, not the less oblig’d by your kind Offer, tho’ we decline accepting it; and, to show our grateful Sense of it, if the Gentlemen of Virginia will send us a Dozen of their Sons, we will take great Care of their Education, instruct them in all we know, and make Men of them.

Divine Wills

When Scunthorpe solicitor R.A.C. Symes died in 1930, his will specified that “in the event of the Second Coming of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ my Will shall (so far as may be legally permissible) come into operation and take effect as though I were dead.”

When retired London schoolmaster Ernest Digweed died in 1976, he left his whole estate, more than £26,000, in trust for Jesus Christ at the Second Coming. The estate was to be invested for 80 years, and “if during those 80 years the Lord Jesus Christ shall come to a reign on Earth, then the Public Trustee, upon obtaining proof which shall satisfy them of his identity, shall pay to the Lord Jesus Christ all the property which they hold on his behalf.” If Jesus does not appear, then the estate goes to the crown.

See Heaven on Earth.

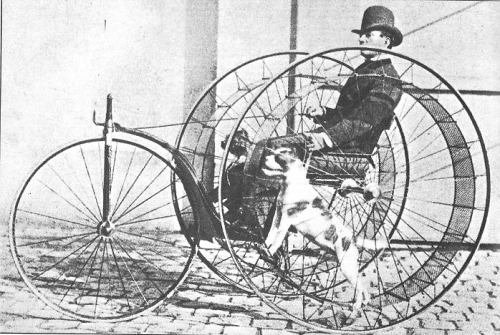

Brute Force

A Paris inventor patented this “cynophere,” or dog-powered velocipede, in 1875.

Twelve years later, a Cleveland designer offered this “motor for street-cars.” That’s progress.

Popularity Contest

Unquote

“The difference between a conviction and a prejudice is that you can explain a conviction without getting angry.” — Anonymous

After Hours

A third case is one of somnocyclism (cycling in sleep). The patient, asleep, sometimes in cycling costume, and sometimes in an undershirt or less, got up, mounted his wheel, and rode about town and in the country. He generally awoke from a fall. On one occasion it was at the foot of a hill, his head on the edge of a pond, and his wheel about thirty feet distant. Another night he found himself suspended by his shirt on a pear tree in his father’s garden. It is not known whether he had descended thither from the roof or was trying to ascend. At other times he would go to his office and work. Once, having stuck over a balance in the afternoon, he found next morning that he had completed it, correcting an error previously not observed. There is no subsequent recollection of what has transpired. He has been observed in hospital to hold a conversation through an imaginary telephone, and again to sit atop a wardrobe with an umbrella up over him. Evidently this man’s disease included a sense of humour.

— G.R. Wilson, “Alcoholism and Allied Neuroses,” Journal of Mental Science, October 1899

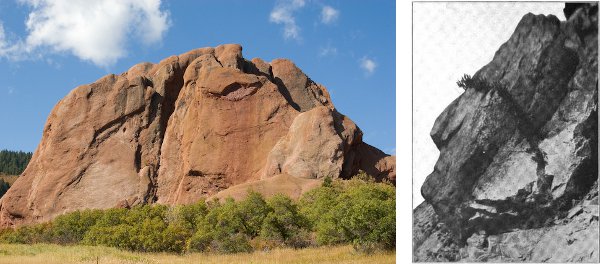

Father, Country

Time and weather have sculpted a likeness of George Washington in Colorado’s Roxborough State Park. It even has “teeth.”

Right: A profile discovered near South Bethlehem, Pa., during the clearing of a mountainside in 1913. “Viewed in profile, the nose, upper lip, eye, and chin are as clearly defined as though cut by human agency,” wrote one observer. “Even the rock formation of the head has a surface curiously like in appearance to the wigs of colonial days.”