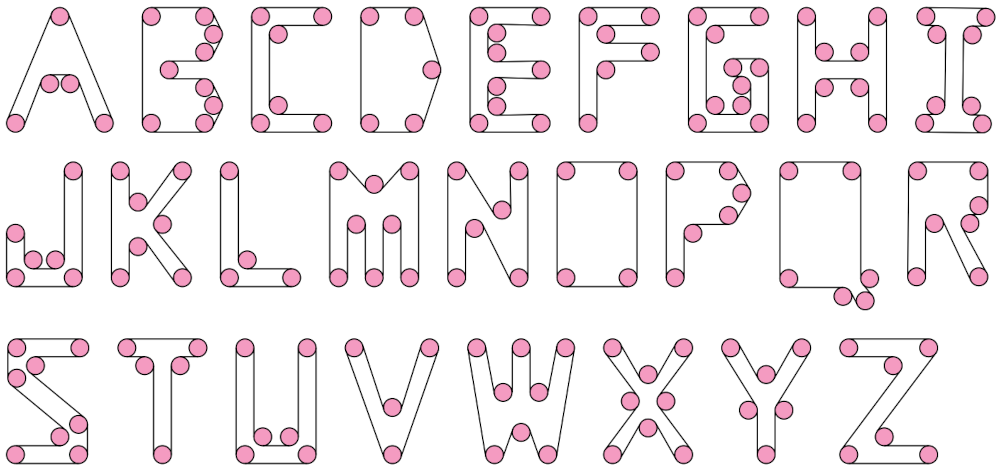

A Belt Font

Suppose you have a collection of gears pinned to a wall (disks in the plane). When is it possible to wrap a conveyor belt around them so that the belt touches every gear, is taut, and does not touch itself? This problem was first posed by Manuel Abellanas in 2001. When all the gears are the same size, it appears that it’s always possible to find a suitable path for the belt, but the question remains open.

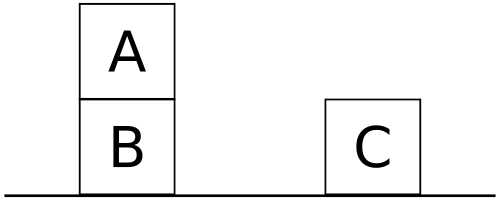

Erik Demaine, Martin Demaine, and Belén Palop have designed a font to illustrate the problem — each letter is a collection of equal-sized gears around which exactly one conveyor-belt wrapping outlines an English letter:

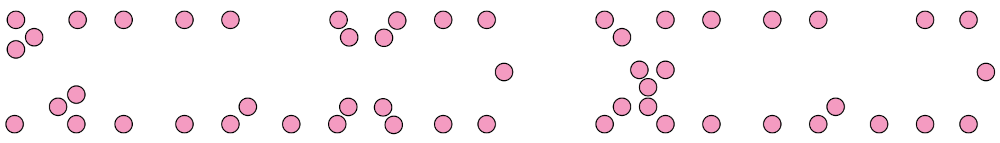

Apart from its mathematical interest, the font makes for intriguing puzzles — when the belts are removed, the letters are surprisingly hard to discern. What does this say?

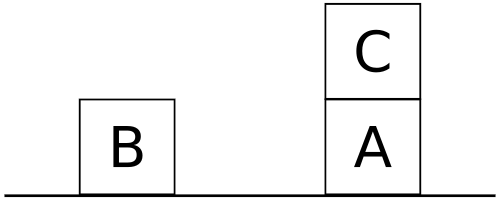

The Sussman Anomaly

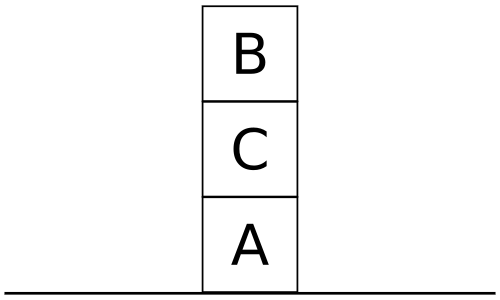

MIT computer scientist Gerald Sussman offered this example to show the importance of sophisticated planning algorithms in artificial intelligence. Suppose an agent is told to stack these three blocks into a tower, with A at the top and C at the bottom, moving one block at a time:

It might proceed by separating the goal into two subgoals:

- Get A onto B.

- Get B onto C.

But this leads immediately to trouble. If the agent starts with subgoal 1, it will move C off of A and then put A onto B:

But that’s a dead end. Because it can move only one block at a time, the agent can’t now undertake subgoal 2 without first undoing subgoal 1.

If the agent starts with subgoal 2, it will move B onto C, which is another dead end:

Now we have a tower, but the blocks are in the wrong order. Again, we’ll have to undo one subgoal before we can undertake the other.

Modern algorithms can handle this challenge, but still it illustrates why planning is not a trivial undertaking. Sussman discussed it as part of his 1973 doctoral dissertation, A Computational Model of Skill Acquisition.

Entre Nous

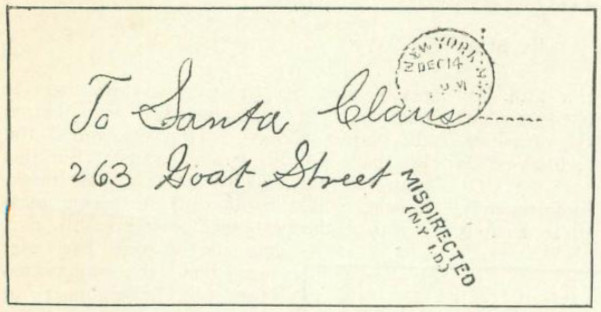

In 1896 the letter above arrived at the New York post office. As there was no Goat Street in New York, the office marked it misdirected and sent it on to Washington, where clerks eventually opened it, looking for further clues. They found this:

Dear Santa, — When I said my prayers last night I told God to tell you to bring me a hobby horse. I don’t want a hobby horse, really. A honestly live horse is what I want. Mamma told me not to ask for him, because I probably would make you mad, so you wouldn’t give me anything at all, and if I got him I wouldn’t have any place to keep him. A man I know will keep him, he says, if you get him for me. I thought you might like to know. Please don’t be mad. — Affectionately, John.

P.S. — A shetland would be enough.

P.S. — I’d rather have a hobby horse than nothing at all.

“I am very sorry to say that John did not get the horse,” wrote Mary K. Davis in the Strand. “Little boys who don’t do as their mothers tell them find little favour with Santa Claus.”

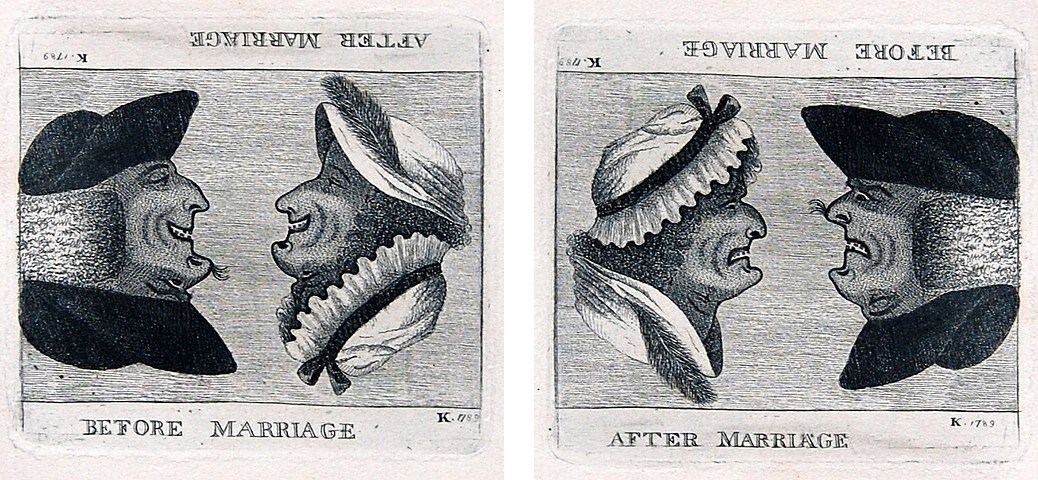

All the Uses of This World

As a footnote to the above, I would like to say that I am getting very tired of literary authorities, on both the stage and the screen, who advise young writers to deal only with those subjects that happen to be familiar to them personally. It is quite true that this theory probably produced A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, but the chances are it would have ruled out Hamlet.

— Wolcott Gibbs, New Yorker, January 6, 1945

In a Word

nimiety

n. superfluity

brachylogy

n. a condensed expression

scrimption

n. a very small amount or degree

perficient

adj. that accomplishes something; effectual

Leonard Bernstein conducts the Vienna Philharmonic without using his hands, 1984:

The Sandwheel

This is a variation on a perpetual motion machine proposed by the Indian mathematician Bhāskara II around 1150. Each of the wheel’s tilted spokes is filled with a quantity of sand. As the tubes descend on the right, the sand within them shifts outward, exerting greater torque in the clockwise direction and thus keeping the wheel turning forever.

Unfortunately the same design ensures that there’s always a greater quantity of sand on the left, so nothing happens.

Matriarch

In 1956, ornithologist Chandler Robbins tagged a wild female Laysan albatross at the Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge in the North Pacific. The bird, dubbed Wisdom, went on to a stunning career, flying more than 3 million miles, equivalent to 120 trips around the Earth. She has been seen at the atoll as recently as last December, making her, at 72, the the oldest known wild bird in the world.

In that time she’s hatched as many as 36 chicks, a significant contribution to the struggling wild albatross population. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service wrote, “Her health and dedication have led to the birth of other healthy offspring which will help recover albatross populations on Laysan and other islands.” Bruce Peterjohn, chief of the North American Bird Banding Program, added, “To know that she can still successfully raise young at age 60-plus, that is beyond words.”

Portal Painting

Steven Novak uses a laser to transfer a scene to the interior of a hemisphere. The completed painting then presents an “accurate” perspective to a viewer looking about from the center.

Dick Termes creates the same impression (via a perceptual illusion) by painting on the convex exterior of a full sphere.

Breathing Exercises

Dmitri Shostakovich’s first opera was a setting of Nikolai Gogol’s 1836 story “The Nose.”

This scene is from the Royal Ballet & Opera’s 2016 staging.

(Thanks, Randy.)