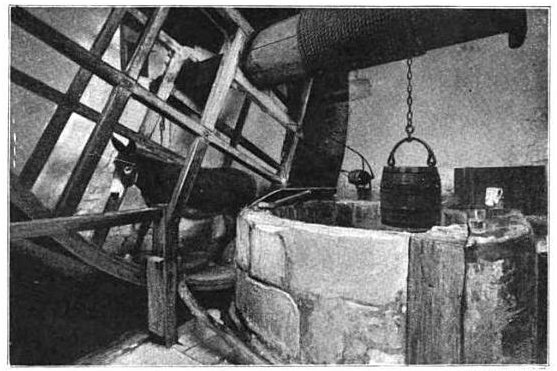

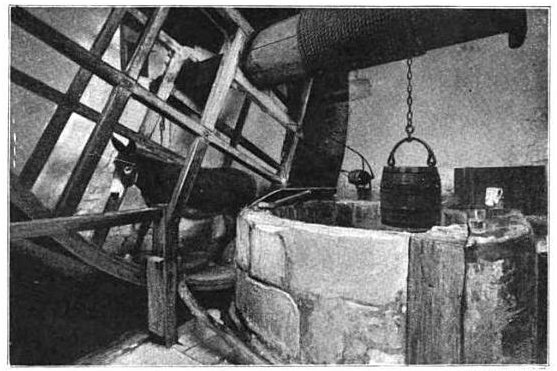

The well at Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight is 200 feet deep, so the residents raise water using an enormous wheel driven by a donkey, a practice that dates to at least 1690.

“While it is not claimed that the same individual donkey has drawn its water all of these years,” wrote a correspondent to American Machinist in 1904, “the claim is made that the duty of drawing water from this famous well descends from father to son, and is never shared outside this one royal family of donkeys.”

“One ass has been known to perform this service at Carisbrooke for fifty years, another for forty, a third for thirty, and a fourth had performed it for ten years at the time of the writer’s last visit,” wrote Caroline Bray in 1876. “The dates are marked down inside the door of the well-house.”

(“The donkey was continuing his labour and looking towards the well when the question was asked, ‘What is he looking at?’ ‘He is looking for the bucket,’ said the man; and, in fact, as soon as the bucket appeared the donkey stopped, and very deliberately walked out of the wheel to the place at which he stood at our entrance, knowing full well that he had done what was desired.”)