Between the Lines

Read the first letter of each sentence of the preface of Transport Phenomena, a 1960 chemical engineering textbook by Robert Bird, Warren Stewart, and Edwin Lightfoot, and you’ll discover the message THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO O.A. HOUGEN.

In the second edition, the initial letters of successive paragraphs spell the word WELCOME.

In the afterword, they spell ON WISCONSIN.

South of Paradise

A village in southeastern Michigan (population 45) has, for years, been enjoying a tourist boom. People would come from all over just to be able to mail a card postmarked Hell or to purchase bumper stickers for their cars stating ‘WE’VE BEEN THROUGH HELL!’ In addition to this attraction, the village has lately acquired a reputation as a marriage mill. Seventy two couples were wed there in 1965 and 61 the following year, a large percentage of them having been divorced at least once. One couple is alleged to have told the local justice of the peace that since they’d already been through Hell twice, they might just as well start there.

— Robert M. Rennick, “Obscene Names and Naming in Folk Tradition,” in Names and Their Varieties, 1986

Brady’s Leap

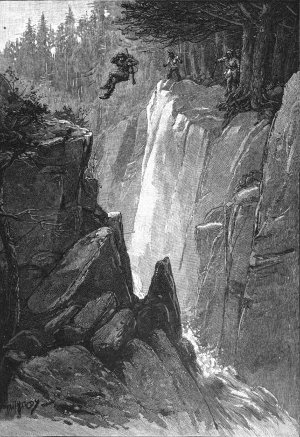

Frontiersman Samuel Brady was being chased through northern Ohio by a band of Sandusky Indians in 1780 when he found his way blocked by the Cuyahoga River:

“He made his way to Standing Rock, and intended to cross at that ford, but the Indians were awaiting him, and he ran farther along the bank, to a place where the rocks rose at some points to a height of twenty-five feet. The body of the river at the narrowest part was from twenty-three to thirty feet wide, and was deep and dangerous. There was no other ford than Standing Rock for miles, and the Indians felt assured of their prize, but faint heart was not known to the Captain of the Rangers, and even a rushing torrent of water did not stop him in his course. Gaining a less precipitous edge of the cliff, he ran back into the forest, to get a good start, and was so near the approaching red men, that he heard their shots and exclamations. Across the expanse of water, at a height of probably twenty or twenty-five feet, he bounded, and with the eye of a practiced marksman, struck the bank on the other side, and stood on the cliff, as the wild yell and wilder appearance of the first pursuer denoted his disappointment and rage.”

Could this have happened as described? The river is broader and its banks much lower than in former times, so it’s hard to judge. The best evidence I can find supporting the tradition is an 1856 letter by Frederick Wadsworth, who writes that “many years ago” he had visited the spot with a companion who had heard the tale from Brady himself. “We measured the river where we supposed the leap was made, and found it between twenty-four and twenty-six feet; my present impression is that it was a few inches less than than twenty-five feet. There were bushes and evergreens growing out of the fissures in the rock on each side of the stream. He jumped from the west to east side; the banks on each side of the stream were nearly of the same height, the flat rock on the west side descending a very little from the west to the east.” Decide for yourself.

(Thanks, Mike.)

Unquote

“He who fears death either fears to lose all sensation or fears new sensations. In reality, you will either feel nothing at all, and therefore nothing evil, or else, if you can feel any sensations, you will be a new creature, and so will not have ceased to have life.” — Marcus Aurelius

Noted

Limericks

A bookworm in Kennebunk, Me.,

Found pleasure in reading Monte.,

He also liked Poe

And Daniel Defoe,

But the telephone book caused him pe.

There’s a girl out in Ann Arbor, Mich.,

To meet whom I never would wich.

She’d gobble ice cream

Till with colic she’d scream,

Then order another big dich.

As he filled up the order book pp.,

He said, “I should get higher ww.”

So he struck for more pay,

But alas, now, they say,

He is sweeping out elephants’ cc.

Both Sides Now

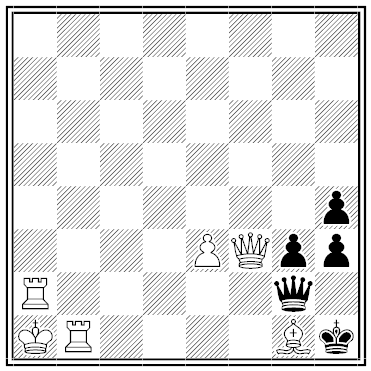

Bach’s “crab canon” rendered as a Möbius strip:

Bach and Handel were both blinded by the same oculist, John Taylor, “the poster child for 18th-century quackery,” according to University of Wisconsin ophthalmologist Daniel Albert. Bach probably died of a post-operative infection; Handel wrote the lyrics to Samson (“Total eclipse! No sun, no moon! / All dark amidst the blaze of noon!”) after Taylor’s botched cataract surgery.

Random Möbius anecdote: In 1957, B.F. Goodrich patented a half-twisted conveyor belt for carrying hot material such as cinders and foundry sand, “thereby permitting each face of the belt to cool during one half of the operating period.”

Waste Not, Want Not

Another gentleman, mentioned in the text-books … seemed to have a ruling passion against waste, which the court respected. The testator devised his property to a stranger, thus wholly disinheriting the heir or next of kin, and directed that his executors should cause some parts of his bowels to be converted into fiddle strings; that others should be sublimed into smelling salts, and that the remainder of his body should be vitrified into lenses for optical purposes. In a letter attached to the will the testator said: ‘The world may think this to be done in a spirit of singularity or whim, but I have a mortal aversion to funeral pomp, and I wish my body to be converted into purposes useful to mankind.’

— Basil Jones, “Eccentricities of Sane Testators,” Law Notes, November 1908

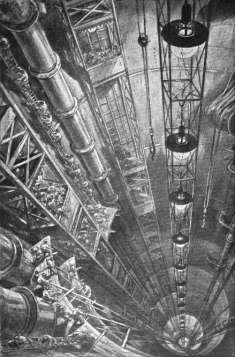

Going Down

What would happen if you jumped into a tunnel that passed through the center of the earth? If you encountered no air resistance, dinosaurs, Mad Hatters, or Morlocks, you’d accelerate until you passed through the center at 18,000 mph, then slow as you ascended through the opposite hemisphere. At the far end you’d have just time to tip your hat to the surprised antipodeans before you fell home again, and you’d continue oscillating like this forever.

“If this shaft had its starting-point on one of the mountain plateaux of South America at an elevation of seven thousand feet,” wrote Camille Flammarion in 1909, “and if it issued at the sea-level at the other side, a man who had fallen into the shaft would arrive at the antipodes still travelling at such a speed that the spectators would see this strange projectile shot to a height of seven thousand feet into the air.”

On the other hand, if our straight tunnel connected two points that were not precise antipodes, then we could install a train powered by gravity — it would roll “downhill” on the first part of its journey, and momentum would carry it through the second (again neglecting air resistance and friction). Curiously, in all these cases the total trip would take the same length of time — about 42 minutes.