sectile

adj. capable of being cut easily with a knife

sectile

adj. capable of being cut easily with a knife

In 1984, grad student Deborah Linville asked students at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute to rate the perceived sexiness of 250 female names. Sexiest (on a scale of 1 to 7) were Christine (5.08), Candace (4.92), Cheryl (4.91), Melanie (4.91), Dawn (4.83), Heather (4.83), Jennifer (4.83), Marilyn (4.83), Michelle (4.83), and Susan (4.83). Least sexy were Ethel (1.00), Alma (1.08), Zelda (1.16), Florence (1.5), Mildred (1.5), Myrtle (1.5), Silvana (1.5), Edna (1.66), Eurolinda (1.66), and Elvira (1.69).

Then Linville asked another group of students to play boss and rate the job applications of eight equally qualified women — submitted under particularly sexy and unsexy names.

Men hired and promoted non-sexy applicants much more frequently than women did. Linville concluded that “there is a prejudice toward women applicants based on the degree of sexiness of their names,” perhaps because men particularly expect female managers to possess strengths, such as motivation and decisiveness, that they don’t associate with sexy-sounding names.

Brothers Alphonse, Kenneth, and Mayo Prud’homme were playing with a foot-long toy cannon in Natchitoches, La., in September 1941 when they saw a man peering at them through binoculars from the opposite side of the Cane River. “We just fired a shot at him to see what would happen,” Kenneth remembered later. “He bailed out of the tree and went flying back down the road in a cloud of dust.”

Presently the man returned with infantry. “They started shooting back at us, and when they’d shoot, we’d shoot back.”

This went on for half an hour, escalating gradually. The boys’ father added firecrackers to their arsenal; their opponents set up smoke screens and readied a .155 howitzer. At last an Army officer appeared at their side and said, “Mr. Prud’homme, do you mind calling off your boys? You’re holding up our war.”

The boys, ages 14, 12, and 9, had interrupted war games involving 400,000 troops spread over 3,400 square miles in preparation for America’s entry into World War II. At the sound of the cannon, George S. Patton had stopped his Blue convoy and engaged what he thought was the opposing Red army. His men were firing blanks, but the maneuvers were real.

“That’s my one claim to fame,” Kenneth told an Army magazine writer in 2009. “I defeated General Patton.”

The following ‘True Copy of a Jury taken before Judge Doddridge, at the Assizes holden at Huntingdon A.D. 1619,’ may amuse our readers. The Judge had in the preceding circuit censured the Sheriff for impannelling men not qualified by rank for serving on the Grand Jury, and the Sheriff being a humourist, resolved to fit the Judge with sounds at least. On calling over the following names and pausing emphatically at the end of the christian, instead of the surname, his lordship began to think he had indeed a jury of quality.

The Judge, it is said, was highly pleased with this practical joke, and commended the Sheriff for his ingenuity. The descendants of some of these illustrious Jurors still reside in the County, and bear the same names; in particular, a Maximilian King we are informed still presides over Toseland.

— The News Magazine, August 1864

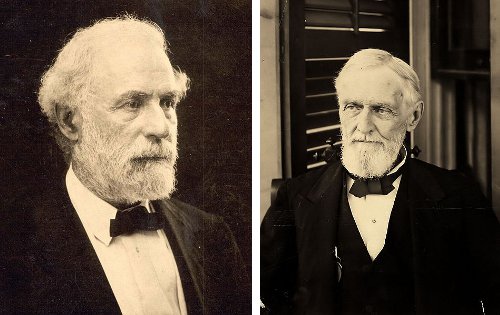

Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis both died without a country.

In 1865 Lee applied for pardon and completed an amnesty oath, fulfilling terms required by Andrew Johnson. But the documents were never recognized, and Lee died without citizenship in 1870. A century later a worker discovered the oath in the National Archives, and Gerald Ford restored Lee’s citizenship posthumously in 1975.

After the fall of Richmond, Davis was imprisoned for treason. When he emerged two years later, his citizenship was denied — he could not run for office, and he could not vote. Like Lee, he passed the remainder of his life without a nation; Jimmy Carter finally restored his citizenship in 1978.

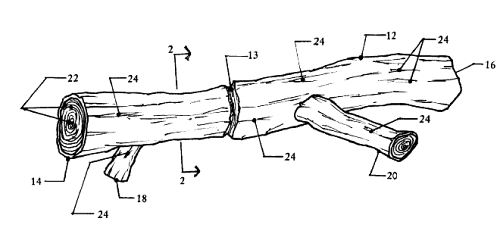

In 2002 Ross Long came very near to patenting a stick:

An apparatus for use as a toy by an animal, for example a dog, to either fetch carry or chew includes a main section with at least one protrusion extending therefrom that resembles a branch in appearance. The toy is formed of any of a number of materials including rubber, plastic, or wood including wood composites and is solid. It is either rigid or flexible.

Presumably the Almighty would have stepped in if He’d considered this infringement.

John T—-, Schoolmaster.

May he be punished as often as he punished us,

He was a hard old shell.

He said the Lord’s Prayer every morning.

May the Lord forgive him as often as he forgave us.

That was never.

We his scholars rear this stone over his ashes

Though they are not worth it.

We are glad his reign is over.

Amen.

— Massachusetts tombstone, quoted in John R. Kippax, Churchyard Literature, 1876

Why do we say “The United States is” rather than “The United States are”? The founding fathers tended to use are — in 1783 John Adams wrote, “The United States are another object of debate,” and the 13th Amendment declares that slavery shall not exist “within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

The standard answer is that the Civil War established the country as a unified nation in the modern consciousness. In 1887 a writer in the Washington Post declared that the war had “settled forever the question of grammar. … The surrender of Mr. Davis and Gen. Lee meant a transition from the plural to the singular.” “Since the civil war the tendency has been toward such use,” confirmed John W. Foster in the New York Times in 1901.

It’s not quite so simple, of course — authoritative writers can be found who used is before the war or are afterward. William Cullen Bryant banned the singular use from the New York Post in 1870, and Ambrose Bierce was pressing for the plural as late as 1909. (In 1881 New Englander C.H.J. Douglas proposed “The United State of America,” but he got nowhere.)

But the standard answer is essentially true. “The rebellion made the State rights and State sovereignty idea very obnoxious to loyal people, and gave corresponding prominence and popularity to the idea of nationality,” observed the New York Times in 1895. “The United States is, not are,” concluded Carl Sandburg in 1958. “The Civil War was fought over a verb.”

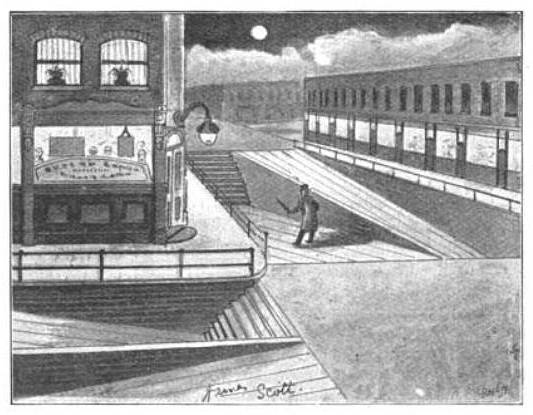

Are we getting lazy, or are our business demands so urgent that great haste in our personal locomotion is absolutely necessary? I am prompted to ask this question because one enthusiast has suggested the peculiar sloping roadways illustrated in Fig. 3. The idea is that by constructing the roads in this rather tantalizing manner, pedestrians could, when they desired, leave the pavement, and after having applied roller-skates to their feet, just stand erect at the top of the slope, and allow themselves to travel down without further effort — unless it be to maintain their equilibrium or to avoid violent contact with fellow-skaters. Arrived at the bottom of a slope, steps would have to be climbed — a difficult matter, by the way, whilst one’s feet are encased in skates — before other slopes could be reached. Certainly, if a very long street were so formed, speed would be assured. But how about vehicles? Where would they be accommodated? I suppose that they would take to the pavements, crossing from one to another by means of the square levels at the street ends. As a pastime, perhaps, this means of progress might be amusing; but it is too ludicrous to commend itself as a serious invention, calculated to be popular in our busy centres of commerce, or, for the matter of that, anywhere within our realms.

— James Scott, “Eccentric Ideas,” Strand, March 1895